It is a fact of life that if you want to achieve net zero you need the technology that can make it happen. You can play around with what you think are smart economic wheezes such as contracts for difference and carbon tax but if you don’t have the technology to enable you to stop burning hydrocarbons then ultimately, they’re of no benefit whatsoever.

Fortunately, this has been understood by some for a long time and the spread of technologies available now is more than adequate to deal with the climate change issue.

In many respects this was to be expected. Those who like me follow energy technology developments around the world as best we can could see this beginning to happen a couple of decades or so ago.

Those countries capable of looking beyond the end of next week recognised the size of the opportunity early on and invested both public and private money into the development and manufacturing of many of the key technologies the planet needs.

Additionally, many of those countries established both educational and research institutes that work with industry on developing those technologies so ensuring their respective countries benefited industrially and economically.

In contrast the UK thought it better to create organisations that would act as an interface between researchers in academia, small companies and big industry to develop research and development projects in which they could co-invest modest sums alongside big industry and organisations such as research councils and development agencies.

The problem with this model is that because of the need to be seen to be doing something it tends to result in a mishmash of projects, few of which are ever going to have a major impact.

As Professor Mariana Mazzucato of University College London has been saying, we need “mission orientated innovation”. In the context of net zero this means investing in projects that meet the “big picture” criteria, by which I mean capable of large-scale power generation or energy production. Today that would mean wind, solar, tidal and hydrogen production and dare I say, small modular nuclear reactors.

Having invested in mission orientated innovation, Denmark can confidently scrap all future licensing rounds for oil and gas exploration and end existing production by 2050 because they have the technology they need to transition quite quickly to net zero. Scotland can’t do that because without oil and gas development, we’d run out of high value jobs quite rapidly.

Denmark is now not only a genuine global leader in wind turbine technology but is rapidly developing its hydrogen technology sector as well.

It’s really time for us to get back to R&D basics and fund what we need.

The UK Government’s recently published Energy White Paper and the route map to net zero also produced recently by the Climate Change Committee are both the sort of documents to which my reaction is one big yawn. Neither said anything particularly new and neither has come up with an industrial strategy.

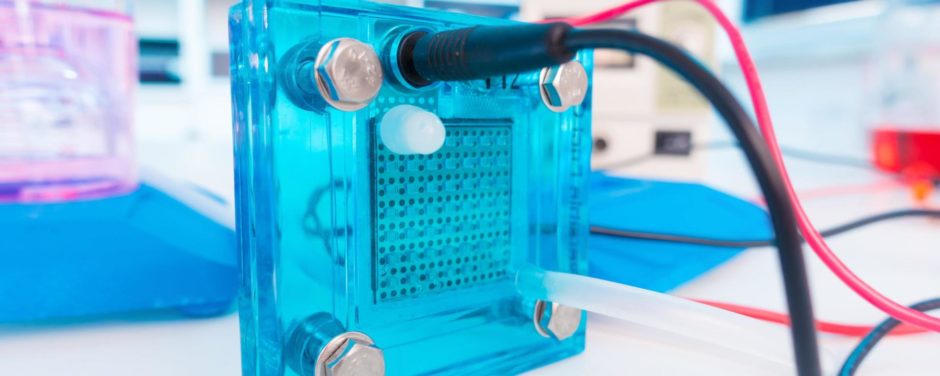

If we need clues on which technologies we should be funding then we could start by looking at the EU Council. They have said that in order to establish a green hydrogen market in Europe, and so help achieve carbon neutrality, they need to install 6GW of electrolyser capacity by 2024 and 40GW by 2030.

ACWA Power, CWP Renewables, Envision, Iberdrola, Orsted, Snam, and Yara have teamed up to set the ambitious goal of driving a 50-fold scale-up in green hydrogen production over the next six years by launching a Green Hydrogen Catapult initiative with the aim of driving down costs to below $2 per kilogram. A quick search on Google suggest this looks achievable with even the Energy and Resources Institute in India saying the costs of making green hydrogen from electrolysis are falling fast, with $2 per kg production costs likely to be achieved before 2030.

Initiatives like this and others should leave us in no doubt hydrogen presents a huge opportunity because of the anticipated size of the global market.

So, let’s focus our R&D efforts on electrolysers, fuel cells and their associated hardware and let’s start now.

Scotland should aim to have a company mass producing electrolysers in less than five years. We have around 6,000 miles of coastline and countless numbers of lochs, river and other water bodies. That we’re not already exploiting that huge resource constantly bemuses me.

We’re already good at tidal energy and heat storage because of the work by Nova Technology, Orbital Marine and Sunamp. We need to scale up tidal and integrate it with hydrogen production.

There’s plenty more to do. For example, we need to improve the heat efficiency of our houses. One way of doing this is to build all future houses to so called “passive house” standards using structural insulated panels. But the insulation is polyurethane foam that uses hydrocarbon as a feed stock. We need a sustainable alternative. Are our universities up to producing that?

Let’s start finding out. We need these technologies. We need the industries that produce them and time is short.

Dick Winchester is a member of the Scottish Government’s energy advisor board

Recommended for you