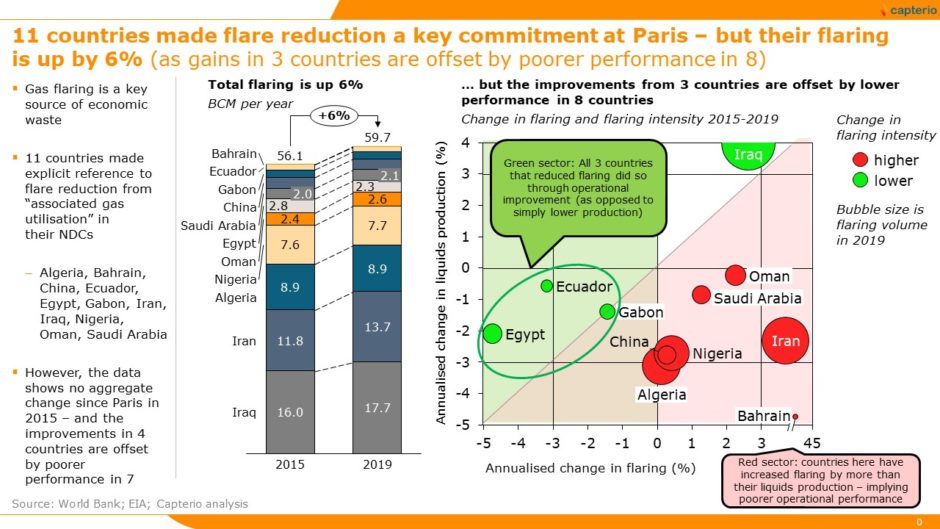

At COP21 in Paris in 2015, 11 countries made gas flaring a stated commitment to their Paris Nationally Determined Commitments (NDCs). Disappointingly, five years on, flaring has increased for these 11 countries, by 6% to 60 billion cubic metres per year.

COP26 is the moment not only for governments to raise ambitions, but also for them to ensure that substantial flaring reduction actually happens. To ensure action, we need undeniably clear top-down leadership and political will from presidents, ministers and oil company executives, backed by multilaterals and others.

Gas flaring is a major source of economic and environmental waste. Globally, 150 bcm per year of gas is flared, according to the World Bank.

That’s large enough such that, if it were a country, “flaring” would be the 5th largest gas-consuming country globally (after US, Russia, China and Iran). The practice leads to an annual revenue loss of $20 billion. Direct emissions from combustion are 280 million tonnes per year of CO2 – but emissions from “methane slip” are substantially higher.

At the COP21 in 2015, 194 states signed the Paris climate agreement and committed to the NDCs. Of these, 11 countries made specific NDC contributions from flared gas utilisation.

On the up

However, since the Paris agreement in 2015, global gas flaring has increased by 3%, from 146 BCM to 150 BCM in 2019. The cumulative waste is some $100 billion in lost potential revenue.

Flaring from the 11 countries that specifically identified flaring as a significant component of their NDCs has increased by 6%, from 56 bcm to 60 bcm of gas – 40% of the global total. This means that we have made no progress over this period, and these countries have performed worse than the global average.

Whilst this is particularly disappointing, the picture varies by country in detail.

Egypt, Gabon and Ecuador reduced flaring. However, these gains were more than offset by increased flaring in eight countries. Flaring intensity (that is the flaring per unit of oil production) has increased by 6.2% in Iran, by 3.3% in Algeria, 3.2% in Nigeria and 3.1% in China.

Therefore, progress since Paris has been very disappointing. The world needs a more concerted effort to reduce flaring over the next five years. Countries (and more than just the 11 from 2015) need to step up their ambition levels.

Capture the flare

Flare capture projects can help to deliver these ambitions. These are projects that capture, store and transport associated gas from oil production sites for power generation and other productive uses.

Such flare capture work can substantially support the energy transition. After all, gas flaring wastes the equivalent of 100 GW of continuous power (almost 900 TWh, 3% of all power generated in 2019) and could displace up to 9% of all coal-generated power.

Many flare capture projects are intrinsically attractive – delivering IRRs in the 20-60% range.

COP26 is the moment for governments to raise ambitions. Gas flaring projects need to be included in the next round of commitments and negotiations.

NOC knock

After all, governments and NOCs are responsible for a disproportionate share of global gas flaring. And these groups can provide the operating and regulatory environment to accelerate flaring reduction.

But ambition without a plan is insufficient. Countries need to deliver actual on-the-ground capture projects. To drive action, producers need to use and act on hard data (much is available already), and governments and regulators need to implement and enforce policies.

We also need new and innovative operating and financing models.

Most of all, we need top-down leadership and political will.

With the US re-joining the global compact and focusing on its own flaring challenges, the world should again concentrate on flaring.

This time, at COP26, we need bold commitments that actually get delivered. The best way to ensure delivery happens is by putting flaring in the spotlight at COP26.

Recommended for you