As 2021 draws to a close and the energy world starts to look ahead to 2022, there seems little doubt that the role of hydrogen will loom ever larger over government energy policy, both here in the UK and globally. So what specifically should we expect?

The starting point is of course developing a coherent hydrogen strategy and indeed the UK government is to be applauded for being one of just 17 countries to do so. Whilst relatively light on detail, more flesh on the bones is expected in 2022 and the government clearly envisages a significant role for the UK in this growing sector.

The two issues at the heart of any hydrogen strategy have to be around driving down costs of production and stimulating demand.

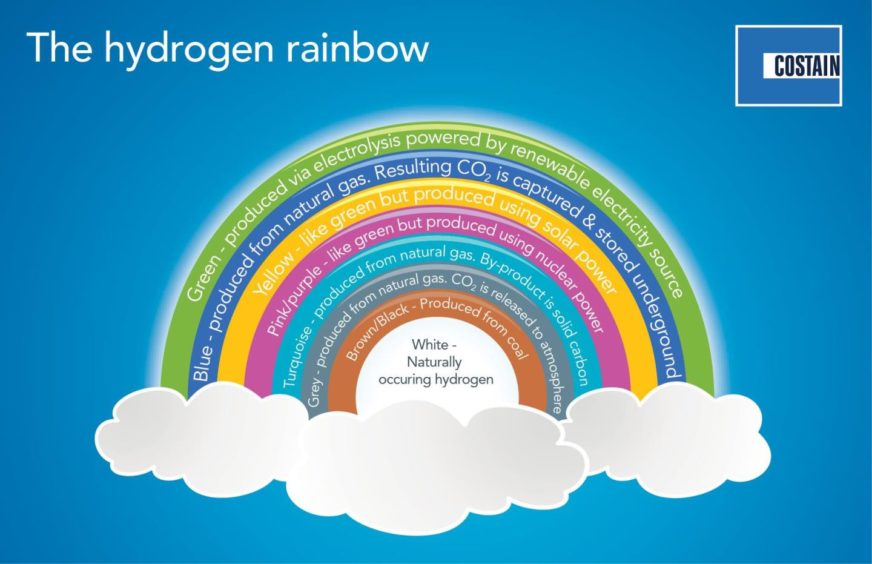

On the first point, government strategy is right to focus on green hydrogen, but also to recognise that blue hydrogen (produced from fossil fuels but with CCUS) is a necessary interim step to reducing emissions and costs of production. Most strategies however don’t yet pay enough attention to “turquoise hydrogen” – produced using methane pyrolysis resulting in hydrogen and solid carbon, so no CO2, which in turn can be used for example as soil improver or in tyre production. Similarly the costs as this technology develops should be much cheaper, with the amount of energy required less than a fifth used in electrolysis.

In terms of blue hydrogen, more should be done by governments in considering the end use of CO2 produced. CCUS should not necessarily mean simply sequestering the CO2 and indeed the recent shortages of CO2, particularly in Europe, points the way to a more considered approach. Aside from ready markets in areas such as food and drink production and packaging, there are a number of other areas where CO2 can actually play a helpful role. The IEA in 2019 identified five areas: fuels, chemicals, building materials from minerals, building materials from waste, and CO2 use to enhance the yields of biological processes. With the right government support, each of these are scalable and indeed in some areas, such as building materials, involve permanent carbon retention.

Perhaps the biggest issue facing the hydrogen market is stimulating demand. Hydrogen has an important role to play in multiple hard-to-decarbonise areas. Transport is an obvious one. We have seen growth in this space and increasing recognition of the potential for hydrogen (whether through fuel cells or combustion) in heavy transport (shipping, trucks, buses, aircraft etc) where batteries for various reasons (space, weight, efficiency) aren’t an effective solution.

Industries such as steel and cement, as well as ammonia, glass and ceramics, are all well placed to benefit from using hydrogen to replace existing fossil fuels. So how to stimulate this demand as current policies are clearly insufficient?

One area already identified by the UK government is effective carbon pricing; expect to see more on this in 2022. Another less talked about mechanism is quotas in certain sectors, and indeed in government procurement. For example requiring all public transport buses to use hydrogen as part of the procurement process is a quick win.

Increasing storage capacity (an area where the UK falls short by international standards) is another. Mandating up to 20% hydrogen in the gas network (as already identified in the government’s strategy paper) would also be a game changer and existing trials are already underway here. However, some of the big wins such as switching the shipping industry to hydrogen will require a global effort and indeed price support in the short term, as well as effective carbon pricing.

2022 will be a year of continued growth and increased investment in the hydrogen sector and governments around the world need to do more, quicker to help that growth. The UK has an opportunity to take a lead and we look forward to the announcements early next year as an indicator of its commitment and ambition in what is a key part of the net zero strategy.

Robin Baillie is a partner at legal firm Crowell & Moring. He has over 20 years of experience, advising clients on energy and infrastructure projects around the world. He has particular expertise advising sponsors and the public sector on renewable energy and infrastructure projects, including the development and construction of a major hydrogen power facility in the UK.

Recommended for you