It is not the snappiest of titles but Ofgem’s Decisions on the new Accelerated Strategic Transmission Investment (ASTI) strategy may come to be seen as a landmark document in the evolution of Britain’s energy industry and the Scottish economy.

Certainly, it represents a dramatic change in mood music which sends out a clear and welcome message. Where excessive regulatory caution has held back developments in the past, the focus now is on delivery by 2030.

Ofgem has always been keen to emphasise its independence from government but such a startling change in approach has not come from a regulator alone. It is pretty clear that Whitehall has told it in very plain terms that it is time to act unambiguously as an enabler of the transition to renewable energy.

Indeed, by confirming 26 projects to upgrade the transmission network in order to facilitate the development of offshore wind, the ASTI plan starts to give substance to the concept of “re-wiring Britain”, a phrase I may have been responsible for at a time when it remained a distant aspiration.

The 26 ASTI projects include the Western Isles Interconnector and seven others directly affecting Scotland which will reinforce the existing grid and carry renewable power to the rest of Britain by 2030, with Peterhead and Torness as critical hubs.

Sudden outbreak of positivity

Understandably, the announcement of a Western Isles Interconnector has attracted most attention because the concept has been around so long. The potential of the islands as a source of renewable energy has been frustrated by 20 years of prevarication, not least on the part of Ofgem.

The game-changer in this respect has been the prospect of two offshore windfarms to the west of Lewis which, added to the consented onshore capacity, already adding up to over 1.67GW of renewable power, against the newly approved prospect of a 1.8GW interconnector.

Tight up to the last minute, Ofgem’s position was in doubt. When they published their proposed list of ASTI projects in August, there were only 24. The two which have since been added are the Western Isles Interconnector, extending underground to Beauly, and an associated upgrading of the Beauly-Denny link.

There is no doubt that the lobbying campaign which took place between August and December, in order to have the project included in the ASTI list, was both necessary and effective. Previously, say Ofgem, they had “insufficient information”. Now however, the language used in the Ofgem conclusions is positively effusive and makes one wonder why it was ever in doubt.

“The Western Isles link”, they say, “is expected to connect a significant amount of offshore wind. Any delay to this link would mean a notable amount of the 50GW offshore wind generation target would not be able to safely connect… to the grid by 2030. Resultantly, this would mean consumers lose a huge quantity of low-cost, low-carbon generation. It would also impact on increasing national energy security and sending clear positive signals to renewable energy investors in GB”.

Needless to say, this sudden outbreak of positivity has been warmly welcomed in the islands. It has taken a long time for their potential contribution to the country’s energy needs to be recognised at all, far less in such glowing terms!

‘The tone of the document suggests a race against time’

However, the positivity of this document is not limited to the Western Isles. Indeed it’s whole “can-do” tone is extraordinary compared to what we have been accustomed to from Ofgem. It is as if the political imperative to deliver on the potential of renewable energy has finally caught up with them and now needs to be implemented without delay.

Regulatory barriers are to be swept away to hasten the process. Planning procedures should be truncated, so as not to act as an impediment to delivery. Both the UK and Scottish Governments are told bluntly that “the current planning regime will need to be modified to reduce the length of time taken for planning permission and necessary consents to be obtained.”

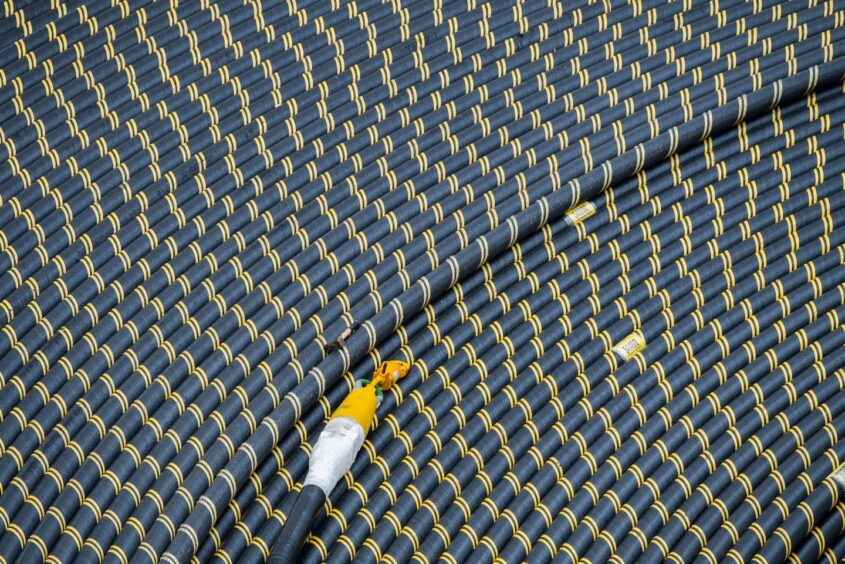

In general, the tone of the document suggests a race against time. One of the reasons for this is that the UK is not alone in a competition for scarce resources. As the document says: “A number of respondents, particularly suppliers, highlighted the current constraints in the supply chain due to increased global demand, particularly for HVDC cable … without early and firm commitments from the Transmission Operators they will not be able to build the required capacity and resources to deliver by 2030”.

In order to allow the Transmission Owners (TOs) – National Grid, Scottish Power, SSE – to get on with the task, the normal rules are being sidelined. “TOs will need to start engaging with the supply chain and progress pre-construction and construction work on ASTI projects as soon as possible’, says Ofgem.

“It is likely that this engagement will need to start before the enabling legislation …. to deliver projects by 2030 they will need to engage supply chains and secure cable manufacturing slots early and therefore need certainty around who will ultimately be the responsible delivery body for all projects before investing”.

There is nothing in this document that is not to be welcomed. Now the challenge is all about delivery. There are huge opportunities for the supply chain, for employment, for skills. Is there enough co-ordination or commitment to meet these challenges? We should know the answer to these questions long before 2030.

Brian Wilson is a former UK energy minister