Much has been written about the economic consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, particularly as the shutdown of the Nord Stream gas pipeline has left the European market scrambling for cover in the form of liquified natural gas (LNG).

Until August 2022 Russia typically supplied around 40% of the EU’s gas demand. In order to make up for this short fall of Russian piped gas the EU has resorted to LNG imports largely from the US and Qatar. The consequences of this move are not only important to gas for heat but also for gas to power.

LNG infrastructure

Regasification capacity in the EU is 160 billion cubic metres (bcm) per year, compared with a total consumption of 412 bcm per year.

Countries with regasification infrastructure is limited to Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Poland, Lithuania, Croatia and Malta. The largest user of gas on the continent is Germany, which has no onshore infrastructure to process LNG.

In the short term, Germany is reliant upon floating storage regasification units (FSRU) which involve greater costs relative to onshore regasification from an LNG carrier.

In the last few months, LNG terminal projects announced across the EU now total 128 bcm – close, but still short of the 155 historically imported from Russia.

LNG and power markets

The EU’s electricity market functions in step like most markets.

The marginal power producer sets the price. The cheapest form of energy dispatches first, namely renewables if the sun shines and the wind blows, then hydro and nuclear. It’s common for renewables not to meet peak demand, therefore gas and coal generators make up for the short fall in generation to cover demand. The last slice of demand met by the highest cost of power sets the power price.

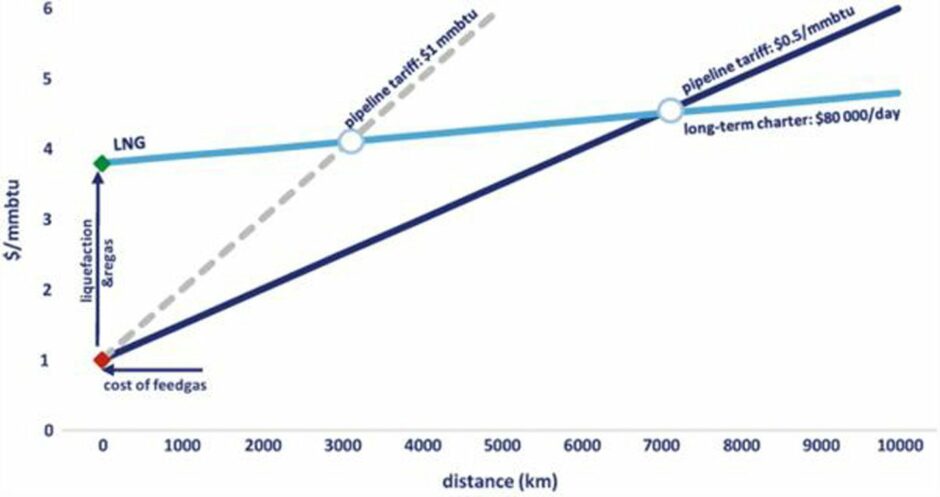

Gas has been the most important fuel source for setting power price across Europe. Consequently, the tight market for gas as a result of the Nord Stream shut down has heavily impacted power prices. To compound this issue, the switch from piped gas to LNG will result in sustained elevated gas-to-power prices due to the cost of liquefaction, transport and regasification. The following chart demonstrates the cost comparisons.

The spread in costs between LNG and piped gas can be as much as 3.8 times. With reference to Europe, the cost difference for the import of US LNG versus piped gas from Russia is approximately 2.3 times – an impact that has so far been somewhat masked by the extremely elevated prices seen since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

If and when gas prices return to long-term averages, the European import of gas via LNG should result in consistently higher gas-to-power prices across Europe.

We see evidence of this long-term impact in the form of power purchase agreements (PPAs). It is now common to see 10-year PPAs at €100 to €140 per megawatt-hour (MWh) – more than double historical averages.

With the levelized cost of power from wind and solar substantially below these levels, we expect that – devoid of grid bottlenecks – the renewables market should witness exponential growth when combined with greater incentives to reduce consumption.

Thus, whilst LNG may be seen as one of the solutions to reducing reliance on gas importation from Russia, the reality is that it locks in long term higher prices – but perhaps a price worth paying?

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Springer/Gergely Mol

© Supplied by Springer/Gergely Mol