Europe’s largest oil companies are banding together to forge a joint strategy on climate change policy, alarmed they’ll be ignored as the world works toward a historic deal limiting greenhouse gases.

Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Total SA, BP Plc, Statoil ASA and Eni SpA are among oil companies that plan to start a new industry body, or think tank, to develop common positions on the issues, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

So far the largest US companies — Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. — have decided not to participate, the people said, asking not be named before a public announcement expected as early as next month.

Efforts to reduce fossil fuel investments and spur renewables such as solar and wind power have gathered pace in the past two years with oil companies sitting largely outside the debate.

One aim of the European producers will be to push natural gas as more climate friendly in generating power than coal, the people said. Of the most used fossil fuels, gas is the one that pollutes the least while coal tops emissions.

“There are companies that are now going beyond the industry’s traditional defensive position by at least appearing to rethink strategy and practices,” said Carole Mathieu, research fellow at the French Institute for International Relations in Paris.

The heads of the biggest European oil producers have been pushing the idea of more active engagement with climate policy in recent weeks.

“If each of us is attacked separately, we will be stronger as a group,” Total Chief Executive Officer Patrick Pouyanne said today in Paris. “If we have an announcement of something, it will be then.”

The industry is slowly waking up to the existential danger to their operations emerging from policies designed to limit climate change. With global temperatures and carbon emissions at a record, governments are looking for a way to clamp down on pollution.

The International Energy Agency, a policy adviser to industrial nations, says half of all fossil fuel reserves may have to remain in the ground to prevent overheating.

“We’re trying to put together a group of people to begin to speak the same language” on climate, BP Chief Executive Officer Bob Dudley said at a meeting hosted by IHS Inc.’s CERA consulting unit in Houston in April. “There’s a bit of different language coming out of different companies and therefore our voice is lost in this.”

Statoil Chief Executive Officer Eldar Saetre has embraced the UN’s goal to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, a level beyond which scientists say will bring disastrous climate change such as more violent storms and rising sea levels.

He set up a renewable energy unit and described steps the industry should follow, starting with a shift to cleaner fuels such as gas, reducing flaring and support for carbon pricing.

“If we don’t, we risk becoming an industry that neither gets access nor acceptance — and that’s not a good thing,” Saetre said at the CERA gathering.

Shell is urging the industry to get out of its defensive crouch and make its views understood. It wants alternative arguments to counterweight the divestment campaign, which has persuaded institutions such as the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and Stanford University to scrap fossil fuel investments.

“In the past we thought it was better to keep a low profile on the issue,” Chief Executive Officer Ben Van Beurden said in February. “It’s not a good tactic. We have to make sure that our voice is heard by members of government, by civil society and the general public.”

The European companies are more sensitive to environmental issues because governments in the region are leading the way on climate and voters are demanding action. The 28-nation European Union plans to cut carbon emissions 40 percent by 2030, double the commitment it made for 2020.

For their part, Exxon and Chevron say there’s little difference in the approach between them and their European competitors. Exxon CEO Rex Tillerson has said he’d speak more openly about the issue and acknowledged the risks of climate change warrant action. He is urging policymakers to consider a global price on carbon emissions and since 2007 included carbon prices in his company’s business planning.

Chevron said today in a statement that it shared the concerns of governments and the public about climate change and action was needed to address the risks. Exxon declined to comment.

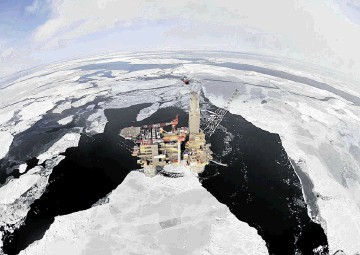

While Europe’s big oil groups present a friendlier position toward climate change, they are continuing with investments that environmental groups sharply criticize, including drilling in the Arctic.

Emissions data released through the Carbon Disclosure Project shows little difference between the U.S. and European oil companies over the past four years. All of the companies have reduced pollution “slightly” since 2011, with BP in the lead mainly because of asset sales needed to pay more than $40 billion in costs associated with a Gulf of Mexico disaster in 2010.

“All companies need to be low-carbon or zero-carbon by 2050,” said Paul Simpson, CEO of the Carbon Disclosure Project, which helps 822 institutional investors with $95 trillion in holdings analyze risks from sustainability issues. “The oil and gas sector is one that doesn’t yet show a clear transition. The longer that goes on, the more concern investors will have.”

Recommended for you