Aberdeen has been selected as the home for the “world’s first” offshore floating facility to produce green hydrogen.

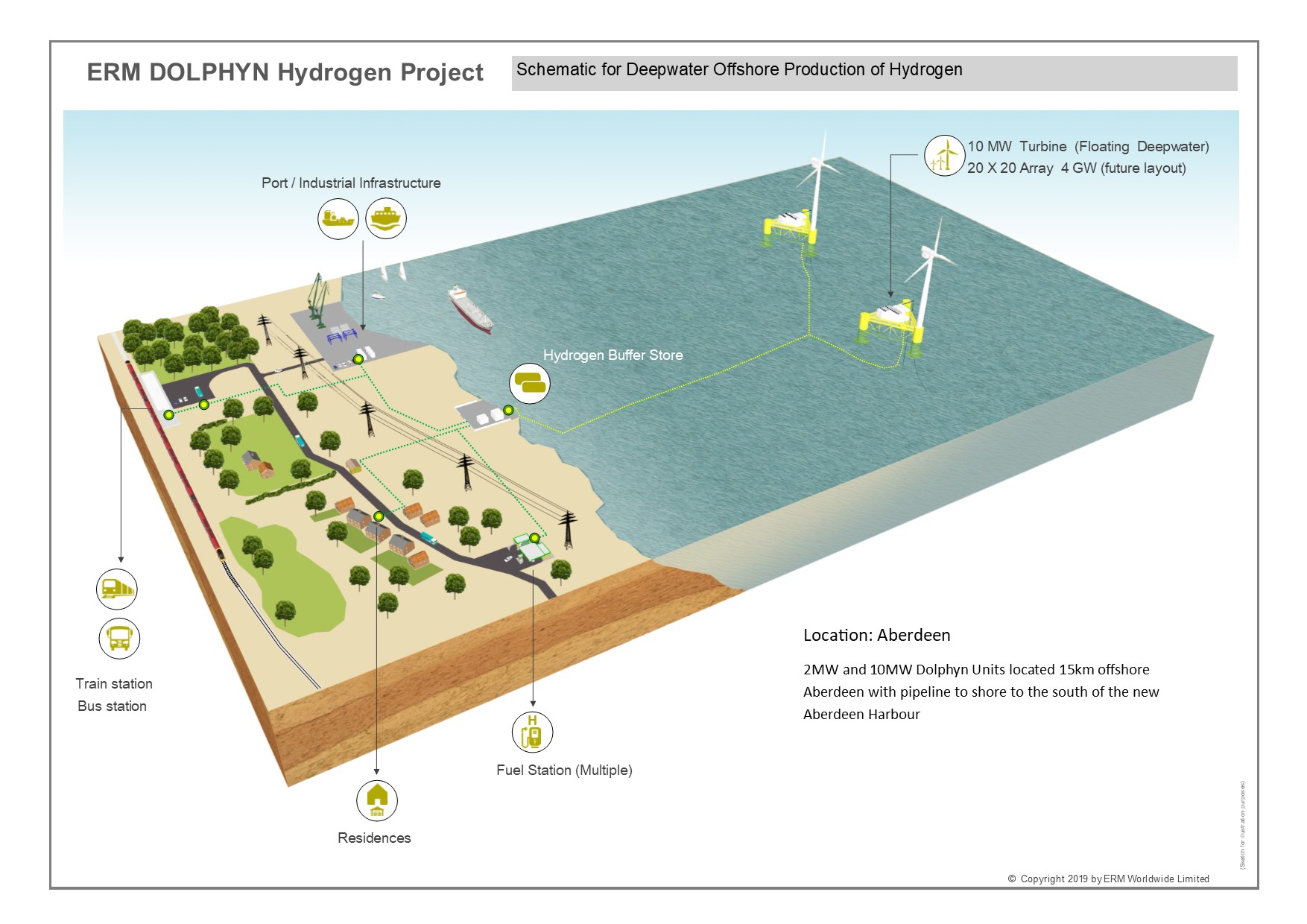

The “pioneering” Dolphyn project will sit 15km off the coast, allowing the UK to harness the power of the superfuel using floating wind turbines.

Developer Environmental Resources Management (ERM) described it as the “start of the process” which will see a predicted wave of thousands of green energy jobs supported by the hydrogen economy.

ERM, a London-headquartered multinational consultancy, who earlier this year was awarded £3million in UK government funding for Dolphyn, said Aberdeen beat out both Orkney and Cornwall for the development.

The company said the decision was due to a number of factors, including the city’s ongoing hydrogen efforts, the new South Harbour expansion, and even some persuading by Sir Ian Wood and Opportunity North East (ONE).

Sir Ian, who chairs ONE, said the move is “very positive” for the region, which is “uniquely positioned to lead the drive towards creating a hydrogen economy”, thanks to its natural resources and oil and gas legacy.

Dolphyn will start with a 2MW prototype in 2024, followed by a 10MW unit in 2027, both of which will lie in the Kincardine Offshore Windfarm.

ERM wants the first commercial 10-turbine (100MW) hydrogen-producing windfarm online by 2030. From then on they’re aiming even bigger – at a massive 4GW wind farm by 2034, enough to power 1.5million homes.

Ultimately, ERM wants to deploy this technology at a large enough scale to replace natural gas needs in the UK and further afield – the firm has projections of creating a network of hydrogen wind farms that could replace 50% of UK gas demand by 2065.

It comes following a report earlier this month from ORE Catapult and the Offshore Wind Industries Council (OWIC) which said green hydrogen could be worth £320bn for the UK economy and support 120,000 jobs by 2050.

Dolphyn project director Kevin Kinsella, based in Manchester, said: “Obviously that’s not going to happen overnight and it’s going to take decades for that transition to happen, but we see Dolphyn as the start of that process.

“Basically the number of jobs would be sufficient to totally replace all of the oil and gas jobs in Aberdeen and surroundings as they are at present.

“So there is the potential to completely transition the oil and gas industry to the hydrogen industry without losing any jobs and, probably, creating a lot more.”

Industry leaders have previously referred to green hydrogen, produced through renewables, as the “holy grail” of clean energy.

By comparison, blue hydrogen is produced from natural gas, with related emissions being captured and stored. A project to do so is being developed at the St Fergus gas plant near Peterhead.

Dolphyn is due to reach a final investment decision (FID) next year and is currently seeking partners to invest in the “whole Dolphyn commercialisation”.

Mr Kinsella said the company is in discussions with a number of energy firms, including three oil and gas companies, so “in terms of getting the investment, I don’t think there’s going to be a problem with that”.

ERM, which is backed by private equity and last year posted revenues of $983m (£772m), said the green hydrogen project will “be great for Aberdeen” and is something they want to promote at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow next year as a “UK achievement”.

Sir Ian Wood said: “This is an exciting development that will enable the UK to harness the huge potential in green hydrogen production from floating offshore wind turbines – many of which will be located off the north-east of Scotland.

“Aberdeen is already recognised as a pioneer in the use of hydrogen for transport purposes and currently boasts the largest fleet of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in Europe.”

However, the former oil tycoon added that Aberdeen needs the “right facilities” such as those which could be housed at the Energy Transition Zone proposed by ONE, in order to “realise the full potential” of green hydrogen and the wider hydrogen economy.

He added: “By developing the energy transition opportunities in the region, we can attract more transformative projects like ERM’s Dolphyn, while creating new jobs in our energy transition supply chain, attracting international investment to realise our net zero ambitions and deliver benefits to communities across the region.”

So how does it work?

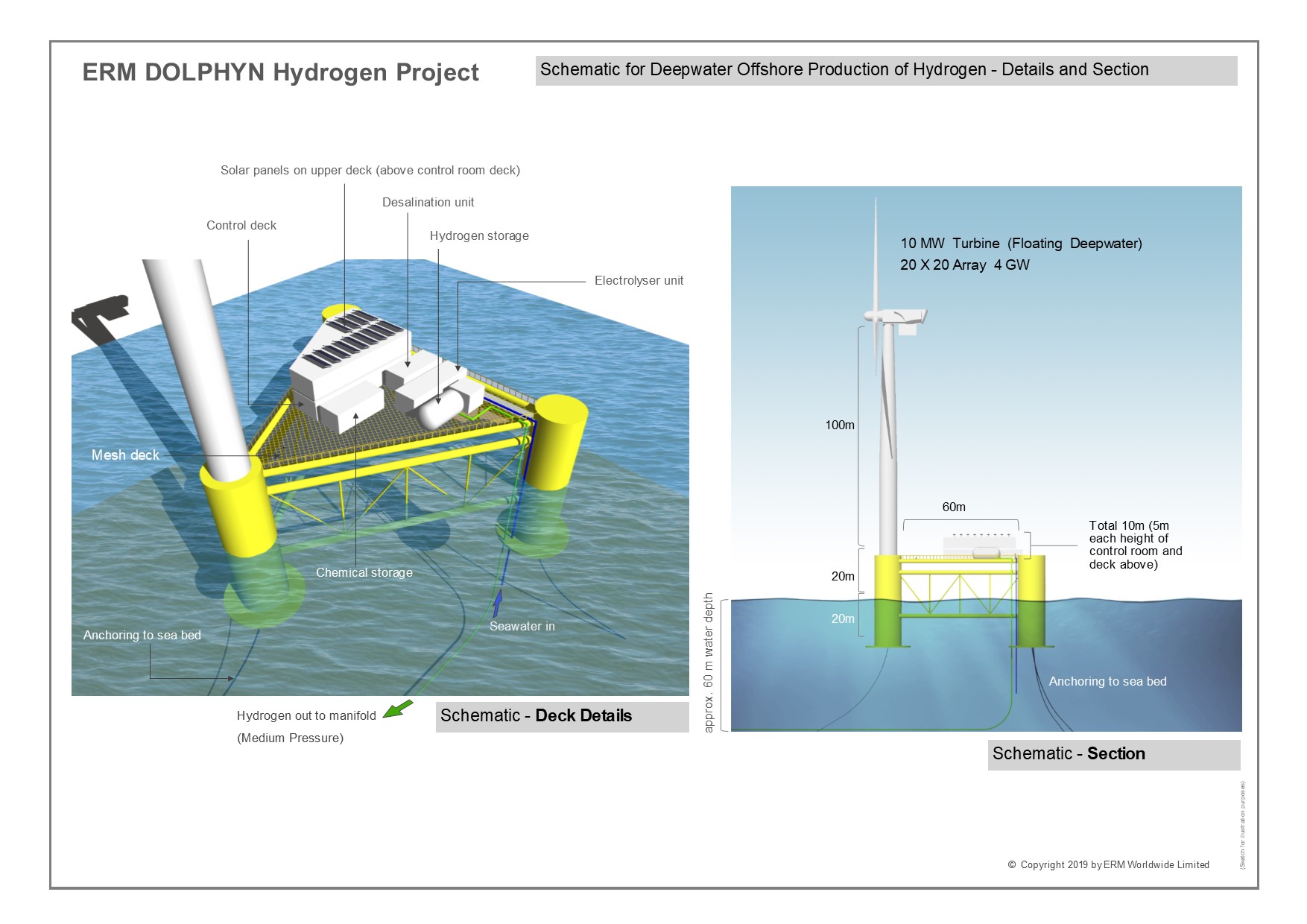

The 2MW prototype, followed by the up-scaled 10MW version, will essentially use wind power to produce hydrogen from seawater.

A pump will take up the seawater, using the power of the turbine to desalinate it, which is then fed into an electrolyser – splitting it into hydrogen and oxygen.

The oxygen is vented and the green hydrogen will be sent back to shore by pipeline – just south of the new Aberdeen Harbour expansion – for use options like buses, ferries and even potentially a hydrogen train.

The initial 2MW prototype will supply about a third of Aberdeen’s hydrogen needs when it comes online in 2024, and thereafter the 10MW version in 2027 will be used more widely in applications such as blending hydrogen into the gas network, up to a certain percentage, as well as marine applications and industrial uses.

The 10MW will be a 100metre tall turbine and a 60metre wide base platform holding the equipment – the initial 2MW will have a smaller platform.

The design is “very similar” to those turbines being used for the Kincardine Offshore Windfarm, only kitted out with technology for hydrogen production.

But what about cost?

ERM’s first 10MW version is described as “pre-commercial”, however, on a large scale, the company predicts a rapid fall in production costs.

If a set of 10MW turbines were deployed on a large 4GW wind farm, as ERM eventually plans, the cost of production could drop from £3.50/kg down to £1.50/kg by 2045.

To give an idea of the overall scale, the 10MW will produce 900tonnes per year, the 100MW will produce 9,000tonnes/year and a 4GW would produce 360,000 tonnes/ year.

ERM estimates a total of 28 such 4GW wind farms could produce enough to totally rid the UK of its gas requirements.

“They’re really big wind farms”, Mr Kinsella said, “They’re 20 x 20 arrays of 10MW turbines.

“But you would only need 28 of those fields and the North Sea has capacity for three or four times that amount.”

As the front-end engineering design (FEED) process nears completion, the company will soon start procuring long-lead items such as the turbine, the substructure and the electrolyser.

Many of these components will probably be constructed in Europe and assembled in a UK port, Mr Kinsella said, adding: “could be Cromarty Firth, could be Dundee. Could even be the new Aberdeen port”.

The thing that “swung it” for Aberdeen was the potential offtake options for hydrogen in the city, such as a refuelling centre in the south, a water treatment facility, and the harbour, which has fuel potential for hydrogen boats.

A larger 4GW development may come to the North Sea – served potentially by the St Fergus gas plant – or the Celtic Sea off Wales, followed by other overseas options including China, Europe and South East Asia.

Mr Kinsella added: “We see the UK as the obvious place to scale it up, we’ve got the world-leading supply chain for oil and gas. We’ve got the industry, the engineers, the expertise we want local to Aberdeen.

“And we’ve got the offshore wind resources which are the best in the world. So it is an ideal place to really scale up the technology.”

Aberdeen city council co-leader Jenny Laing said: “Dolphyn is further evidence that Aberdeen provides a first-class environment for investment in energy transition” after more than “20 years with over £5bn of investment in projects” in regions around the north-east coast.

Fellow leader Douglas Lumsden said it builds on that “momentum” and Dolphyn sends a message that “Aberdeen is able to offer immediate and significant inward investment opportunities that will ultimately keep people here and provide jobs”.