The debate around which direction the UK should take in terms of blue or green hydrogen is complex.

Costain, the smart infrastructure solutions company, has a dedicated team leading the deployment phase of the South Wales Industrial Cluster (SWIC),and is involved in decarbonisation initiatives across the UK. It is well placed to evaluate how each strategy can contribute to the efforts to reach the UK’s net-zero targets. As energy demand continues to rise, both green and blue hydrogen have a role to play on the path to reaching net zero by 2050.

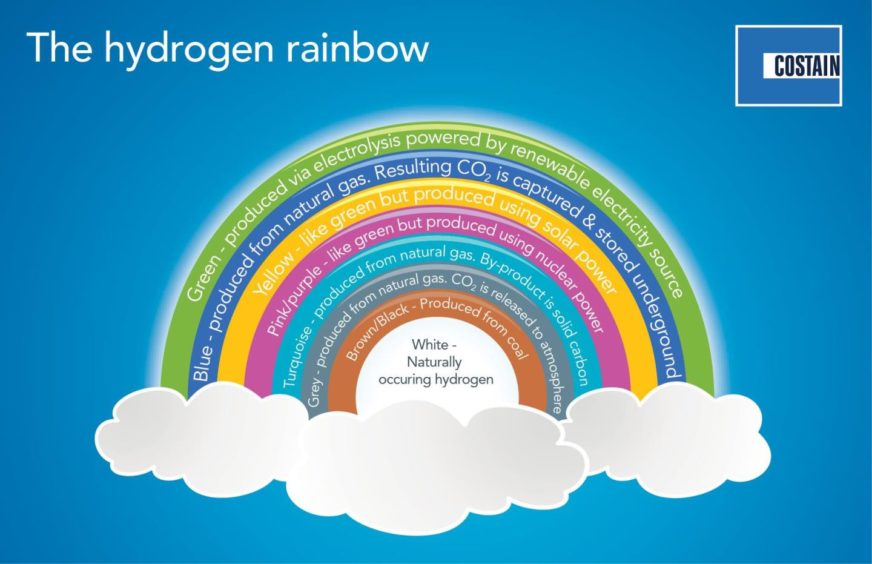

Hydrogen can be produced by a variety of methods, and to differentiate between them, they are referred to as different colours, see below. Blue and green hydrogen are the focus for this discussion. Blue hydrogen is produced by an industrial process which converts natural gas into hydrogen. The process also produces CO2, which is then captured and stored safely underground. Green hydrogen uses an electric current, produced from renewable resources, to split water molecules, producing hydrogen and oxygen.

There are varying opinions on the way forward; some argue the need for blue hydrogen on pragmatic grounds, whilst others endorse using only green hydrogen based on applying a sustainable approach. Complete decarbonisation using renewable technologies alone, however, is unlikely to be feasible, either at present or by 2050, without significantly reducing the energy we use.

The growth of electric vehicles and their planned dominance (and the need for charging infrastructure) will put pressure on the electricity grid. To produce enough clean electricity to both decarbonise the UK’s existing electricity demand and also address other fossil fuel consumption by electrification would require a huge increase in renewable power sources in a very short time.

The government has already stated its intention to ban domestic gas boiler installations in all new homes by 2025, bringing focus onto hydrogen, which must have a role in feeding into what is the biggest use of gas. At the same time, the cluster programmes (SWIC, Humber, Teesside, Scotland and North West England) will be focusing on decarbonising the larger industrial gas users such as power stations, steel, cement and chemical plants.

Infrastructure has a critical role to play. The existing gas network is currently being tested by Costain and gas grid operators for its effectiveness to transport hydrogen around the UK, as is the blending process for creating a mix of gas and hydrogen.

All these activities highlight the importance of establishing a reliable source of hydrogen as soon as possible to allow hydrogen technologies to be developed and begin to break our reliance on natural gas. Indeed, the UK Government has set a target for the production capacity of low carbon hydrogen of 1GW by 2025 and 5GW by 2030. While the ideal situation would be to do this with green hydrogen, the development of commercial scale electrolysers capable of replicating a minimum of 100MW of power generation is still some way off.

In contrast, blue hydrogen production is well understood. The technology to create hydrogen from natural gas at scale is in operation across the globe, and carbon capture and storage requires adaptations of processes already in use. Blue hydrogen is the only viable option to produce the volumes of hydrogen required in the short term and will act as an interim step while the required volumes of green hydrogen, and the clean energy required to power it, are developed.

Thankfully, in practice, hydrogen molecules are “colour blind” so any infrastructure developed to support the end use of hydrogen based on initial production of blue hydrogen can readily transition to green hydrogen in the future.

To learn more about how Costain is shaping the UK’s energy landscape, visit www.costain.com/energy

Recommended for you