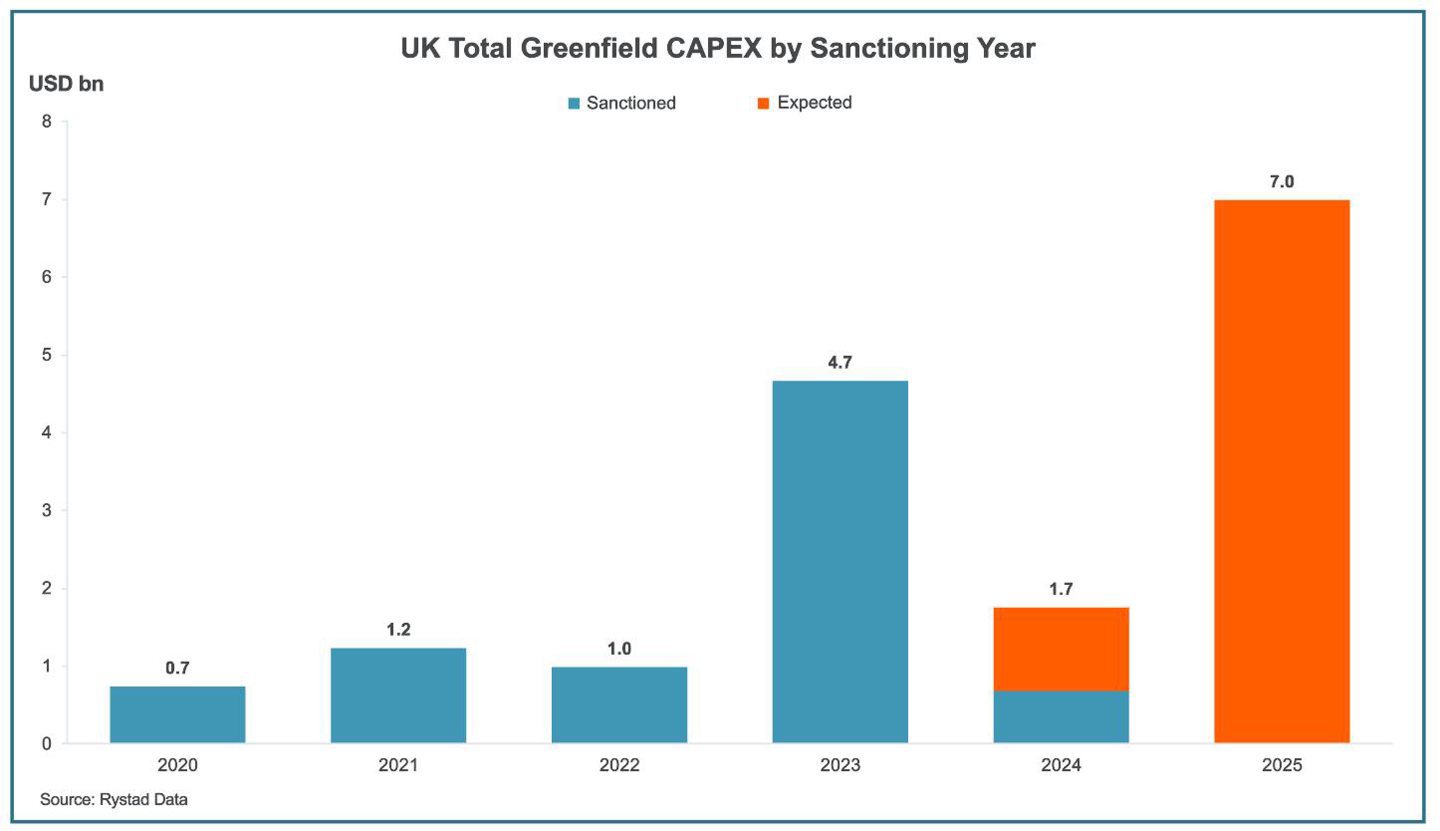

Global sanctioning activity for the upstream oil and gas [O&G] industry is forecast to reach $126bn in 2024, which compares to $179bn recorded in 2023.

Although there is a drop in activity in 2024, O&G project sanctioning is expected to increase in 2025, matching 2023 levels. The UK sanctioning outlook follows a similar pattern.

Despite a two-decade issue of nearly 1,700 new O&G licenses, the UK’s energy security has become a topic of increasing focus. Between 2004 and 2023, the UK awarded 1,680 new licenses to companies to extract O&G in the North Sea.

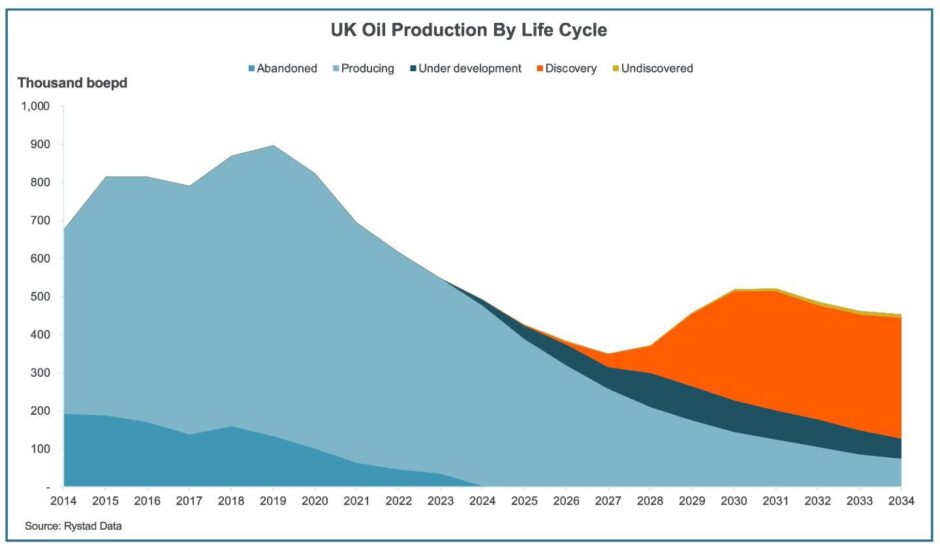

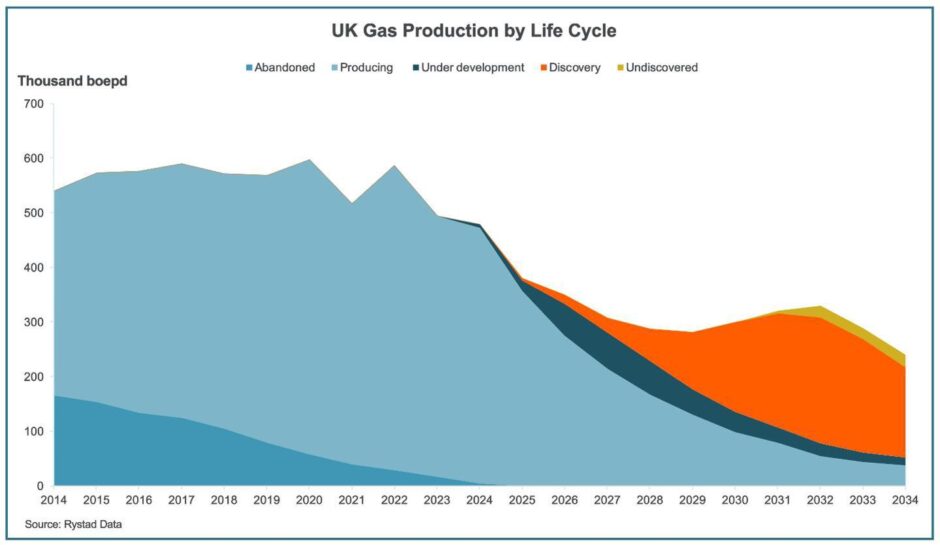

During this period, UK oil exports surged from 68% to 81%, while domestic oil production fell by 60%.

This comes against a complex background: the UK’s refinery capacity and its ability to handle its own hydrocarbons has fallen sharply during the same period.

The UK is a net importer of O&G, with most of the UK’s oil being exported to Europe to be refined into the products demanded by the UK market.

The UK is becoming more dependent on O&G imports from Norway and the USA, with imports from these countries more than doubling between 2021 and 2022.

Oil and gas investment challenges

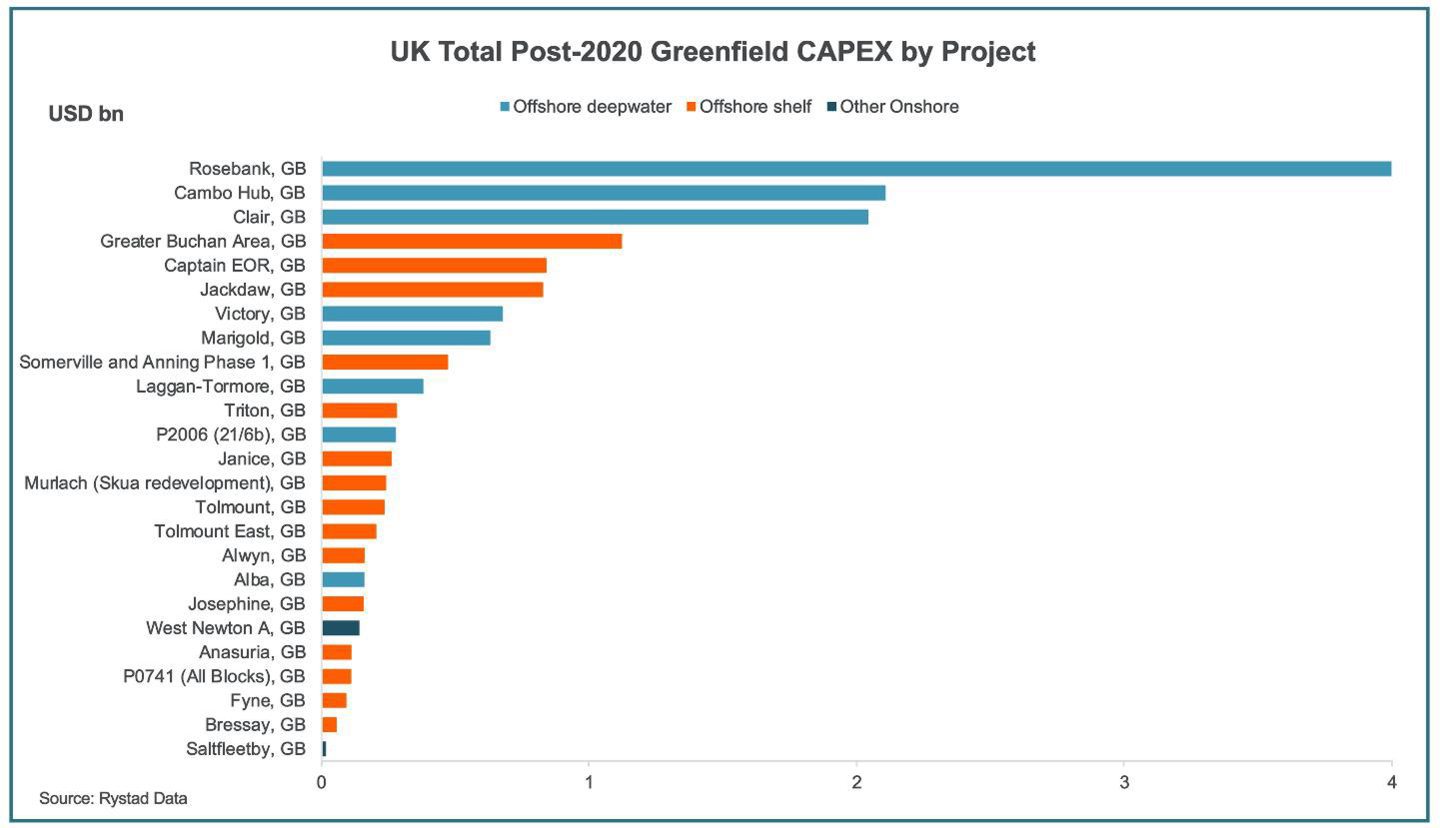

Currently, the UK O&G sector faces several key investment challenges, such as inconsistent political support, having had 6 new energy minister since 2018, and high taxes.

These deter investment in new projects, negatively affecting domestic O&G production volume and increasing the country’s reliance on foreign supply.

It is estimated that the windfall tax will lead to an approximate gap of 85% between consumption and production of O&G in the UK by 2030.

As companies face diminished profitability and scale down investments in new projects, substantial job cuts will follow.

A key point to note is that it is demand that drives emission levels – not supply.

A population cannot change the way it uses energy overnight. If the UK stops extracting its own O&G, without an equivalent reduction in demand, then imports and costs will have to rise with no reduction in overall emissions.

Therefore, it should be common sense for the UK to make the most of its own domestic supply and reduce reliance on other countries, while bringing in tens of billions of tax income and thousands of jobs into the economy.

In addition, indigenous supply will not only cut import premiums, but will also lower the related transportation costs and carbon footprint.

Energy transition a marathon

The energy transition is a marathon, not a sprint.

Perhaps this realisation is behind the Scottish government’s decision to abandon its ambitious climate target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 75% by 2030.

The annual climate targets could also be scrapped, as 8 of the last 12 targets have been missed.

This shift in direction is also echoed by major players in the industry. Despite increasing discussions around sustainability and energy transition, Shell and BP recently made changes to their net zero policies, both pivoting back to their O&G roots and reducing their commitments to low carbon investments to 2030, with 85% of spend beyond 2025 earmarked for conventional energy. This reflects the sustained demand for fossil fuels to meet the current energy needs.

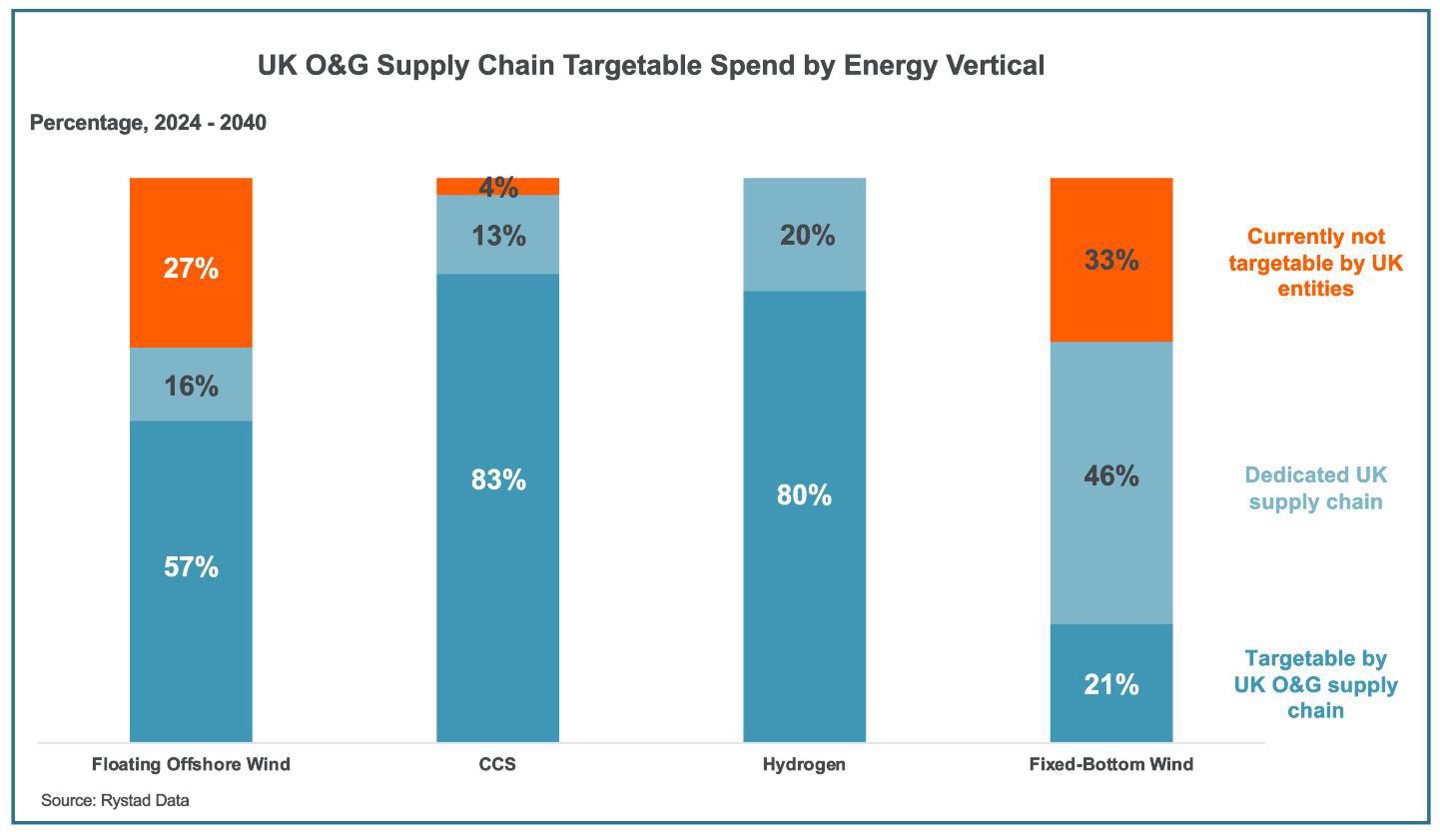

It is important that companies continue to leverage their strengths in O&G as research by Rystad Energy shows that the O&G sector’s supply chain possesses between 60% to 80% of the capabilities and capacity required to develop the UK’s new energy verticals of floating offshore wind, CCS and Hydrogen.

With reducing North Sea investment, there is a risk that the UK energy supply chain is not poised to deliver on and support the opportunities in the energy transition.

The UK has the potential to be a leader in new energy, but continued investment and support for the supply chain is required to retain and grow capacity and capability.

This serves as a reminder to policymakers and the industry that if investment in the current supply chain is unlocked, the UK can build the low carbon energy systems of the future and capture an estimated £150bn opportunity through to 2040.

To achieve a successful and smooth energy transition the UK needs strategic investment in the supply chain to prevent erosion of its world class capabilities, supportive long-term policies, and a globally competitive tax system.

Recommended for you

© Piper Sandler/Rystad Energy

© Piper Sandler/Rystad Energy

© Piper Sandler/Rystad Energy

© Piper Sandler/Rystad Energy © Piper Sandler/Rystad Energy

© Piper Sandler/Rystad Energy