A university researcher is helping to shed light on Russia’s nuclear energy legacy established during the Cold War.

Dr Egle Rindzeviciute was granted entry to a number of the country’s once secret nuclear power plants as part of an international team of academics investigating the impact of the atomic industry across Russia, Ukraine, France and Sweden.

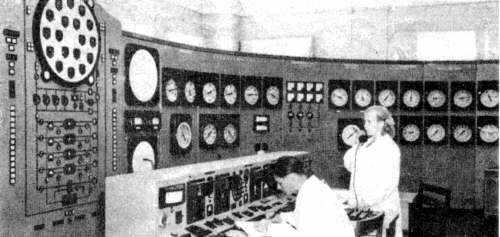

The researcher and lecturer in Criminology and Sociology at Kingston University explored the archives of the Polytechnic Museum in Moscow and gained access to the world’s first commercial nuclear power plant in Obninsk, a city situated about 70 miles from Moscow.

Once shrouded in secrecy, the site lay at the heart of the nation’s nuclear weapon planning during the Cold War era.

The Cold War was a period of history following the Second World War when tensions ran high between Russia and the United States as both countries ramped up their nuclear arsenals.

Seventy years on, the Obninsk Institute of Nuclear Physics and Power is now developing a memorial complex dedicated to celebrating the origins of nuclear energy in Russia.

Dr Rindzeviciute, who is researching shifts in Russian governmental nuclear heritage policy, said the country has chosen to open up on its nuclear past by commemorating the bygone era of the Cold War nuclear power development.

“We are beginning to see a turn in how Russia wants its nuclear identity to be seen. In the former Soviet Union, achievements in science and technology – especially related to space and nuclear power – were intended to demonstrate the superiority of the communist regime,” said Dr Rindzeviciute.

“This era is now becoming viewed with nostalgia and reminiscence, although risks associated with nuclear power are not always being explicitly explained.”

According to Dr Rindzeviciute, the state’s nuclear corporation Rosatom is investing seriously in the cultural heritage and seeking to manage the public perception of Russia’s nuclear legacy.

She said: “Rosatom have established a special centre for history and culture, which oversees about one hundred nuclear heritage sites in the country. While some historical sites and objects, such as the Lenin Nuclear Icebreaker in Murmansk are open to the public, others, such as Sarov Museum of Nuclear Weapons, are closed to foreign visitors.”

Dr Rindzeviciute believes her access to the Obninsk nuclear power plant demonstrates Russia’s pride in showcasing the facility to select groups, including foreign diplomats, business people, nuclear scientists and Western academics.

She said: “It is regarded as an example of Russian innovative ingenuity and they are eager to show it off to science and industry leaders.”

Earlier this year Dr Rindzeviciute was invited to share her findings in a workshop at Harvard University in the United States, where she concluded that question marks over the cultural significance of nuclear sites and their roles for the future was not unique to Russia.

She said: “All nuclear countries face unresolved issues regarding how they engage with the public and manage nuclear energy.”

She is also keen to emphasise the importance of government bodies such as Russia’s Rosatom in the nuclear debate. “History shows that secrecy is not a viable approach from a long term perspective. It is therefore imperative that Rosatom continues to open up to cultural reflection on the nuclear industry. It is vital to foster international cooperation in this area.”

Kingston University will continue to be engaged in the forefront of debates on the nuclear past and the future, with a grant of over £90,000 being awarded to the University over 2018-2020 as part of the Atomic Heritage Goes Critical: Community, Waste and Nuclear Imagination project.

Recommended for you