If a green ride-sharing service were to flourish anywhere it would be in Munich, where you can rent no-emission cars on just about any city-center street. And yet Linde AG is about to shut its two-year experiment with hydrogen.

It’s another setback for fuel cell-powered cars against those that run on batteries.

But the dirty little secret about clean cars is that a decade after Tesla Inc. left hydrogen technology in the dust by putting its first all-electric sedan on the road, automobile executives still think cars that emit only water are the way of the future.

“We’ll keep the fuel-cell technology in development so that we have this technology option should there be a shift in the market,” said Ola Kaellenius, head of development at Daimler AG, which is about to market its GLC F-Cell sport utility vehicle that can drive 500 kilometers on a single tank.

A KPMG survey last year found most senior automotive executives believe battery-powered cars will ultimately fail, with hydrogen offering the true breakthrough for electric mobility. That’s what Japan is banking on—Toyota Motor Corp. is making a big bet it will triumph over batteries.

Of the almost 1,000 officials polled by the Dutch advisory, some 78 percent said hydrogen cars will prevail because their tanks can be filled in minutes, making recharging times of 25-45 minutes for battery options “seem unreasonable.”

Elon Musk famously dismissed fuel cells as “mind-bogglingly stupid”

You wouldn’t guess it by looking on the roads or in auto showrooms today. Just compare BMW’s one fuel-cell car to its plans for 10 battery-powered models by 2022 and you can get a sense of how far behind hydrogen has fallen.

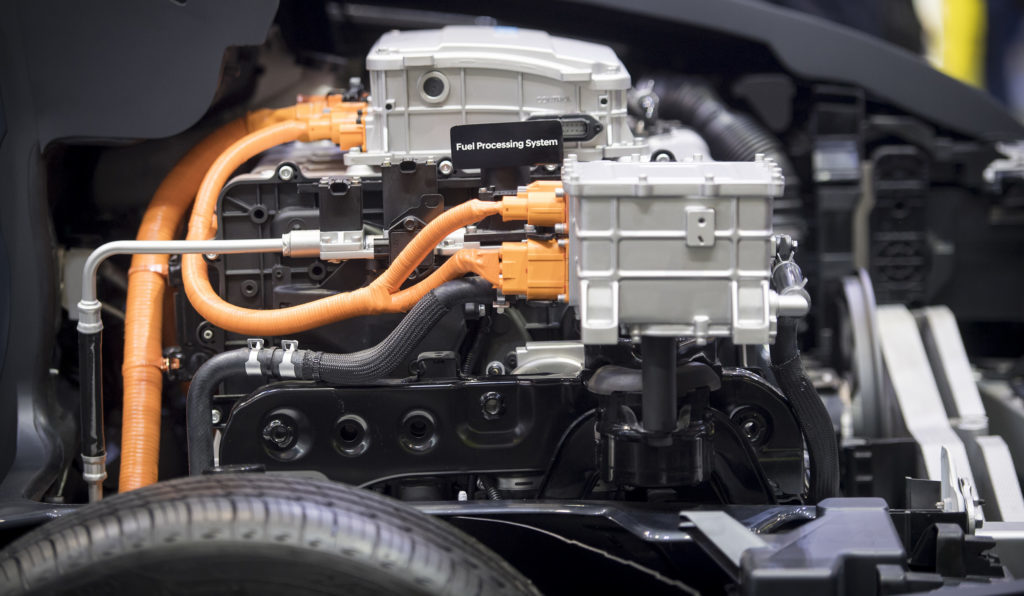

When zero-emission transport first captured the public imagination in the 1990s, hydrogen was just as promising as batteries, not least because fuel cells can run for a lot longer. Unlike liquid gasoline or diesel, a tank of pressurized hydrogen creates electricity by chemically fusing with oxygen in the air.

Yet with the rise of Tesla, whose founder Elon Musk famously dismissed fuel cells as “mind-bogglingly stupid,” the option of powering automobiles with the Earth’s most plentiful element was sidelined in the mainstream conversation.

“It almost feels like a Betamax versus VHS moment,” said Justin Benson, KPMG’s U.K. head of automotive, referring to the war between rival videotape formats in the late 1970s that VHS, considered technologically inferior, eventually won. “It’s not beyond the wits of man to move to hydrogen relatively quickly, if organizations wanted to do it.”

There are pockets of investment. Japan wants fuel-cell cars and buses made by its automakers to transport athletes during the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, and California has spent $100 million building fueling stations. But China, the biggest car market, is going full tilt in the switch to battery-powered cars to combat air pollution.

In 2016, Munich became the first city to offer a car-sharing service—called BeeZero—comprising only fuel-cell-powered hatchbacks. Each of the 50 H2-powered Hyundai ix35s available to rent can run 600 kilometers on one tank, compared with 200 kilometers for BMW AG’s battery-powered i3. But BeeZero has struggled against BMW AG-owned DriveNow, a 700-large fleet of battery- and fuel-powered rental cars. Linde said it would close it on June 30 because it’s not “economically viable.”

Cost is part of the problem. Huge investments in lithium-ion battery technology are quickly pushing prices down of this segment of electric vehicles. A BMW i3 retails for 37,550 euros ($46,200), compared with at least 65,450 euros ($80,600) for the Hyundai ix35.

Add to that the limited availability of fuel-cell filling stations and how tricky it is to extract hydrogen from other elements it binds to, and plug-in electric cars feels more immediately feasible. There are four hydrogen stations in and around Munich, and a total of 30 in Germany, compared with hundreds of public charging stations for batteries.

The Hydrogen Council, formed by energy and auto companies last year, is urging governments to invest. Since fuel cells store energy more efficiently than fossil fuels, they can heat buildings, power industrial machines and generate electricity in areas with limited access to wind and sunlight.

“It’s a bit of a chicken and egg problem,” said Wolfgang Bernhart, Munich-based partner at consultancy Roland Berger. “The challenge actually, like with batteries, is infrastructure. But the initial investments for transportation uses is significantly higher.”

He says there’s a chance for fuel cells to carve out a niche among long-haul lorries, trains, buses and ambulances that would benefit from longer driving ranges and could easily set up fueling pumps at their bases. Germany plans to bring 14 hydrogen trains into service in Lower Saxony from 2021 able to go 1,000 kilometers on one tank.

While they’ll be stuck at less than 2 percent of automobile sales through 2030, fuel-cell cars will eventually be vindicated, according to forecasts of the European Climate Foundation, reaching 10 percent by 2035, 19 percent by 2040 and 26 percent by 2050.

That’s why many carmakers are keeping a toe in the H2O. At the consumer electronics show in January, Hyundai unveiled a fuel-cell powered SUV, the Nexo, which it says can run for up to 800 kilometers—40 percent more maximum range than Tesla’s Model X.

“If you want to have a million electric vehicles on the road, fuel cells are going to have to be a part of it,” said Andreas Broecker, head of innovation at Linde. “The public still doesn’t really know that fuel-cell technology is part of electromobility. That should be made clearer.”

Recommended for you