Carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS) is often described as a key part of energy transition, with the ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from existing energy supplies.

However, development in the UK to date has proven fragmental.

There are currently more than 20 large-scale CCUS projects operating globally but no commercial scale projects operating in the UK.

However, as the conversation around energy transition gains renewed focus in 2019 along with a new statutory commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050, perhaps CCUS’s time has finally arrived.

In July, the UK Government’s energy department published two consultations relating to CCUS. The first focused on CCUS business models and the second on the re-use of oil and gas assets to transport and store carbon dioxide in depleted reservoirs as part of CCUS projects. The deadline for responses is September 16.

Against the background of the two previous cancelled competitions, the UK Government recognises that to ensure the delivery of CCUS, a supportive policy environment is vital.

The previous “full-chain” approach was predicated on projects that bundled together the entire capture, transportation and storage asset chain. However, the risk profiles for those different elements vary considerably.

The key proposal of the business models consultation is to have a separate support model for CO2 transport and storage from that which supports the carbon capture elements of any CCUS project, thereby allowing for flexibility.

From the perspective of traditional oil and gas companies, the re-use consultation may attract greater interest.

Re-use of infrastructure will be relevant in the context of the statutory requirement to “consider potential re-use opportunities” before submitting a decommissioning programme for approval, as introduced by the Energy Act 2016.

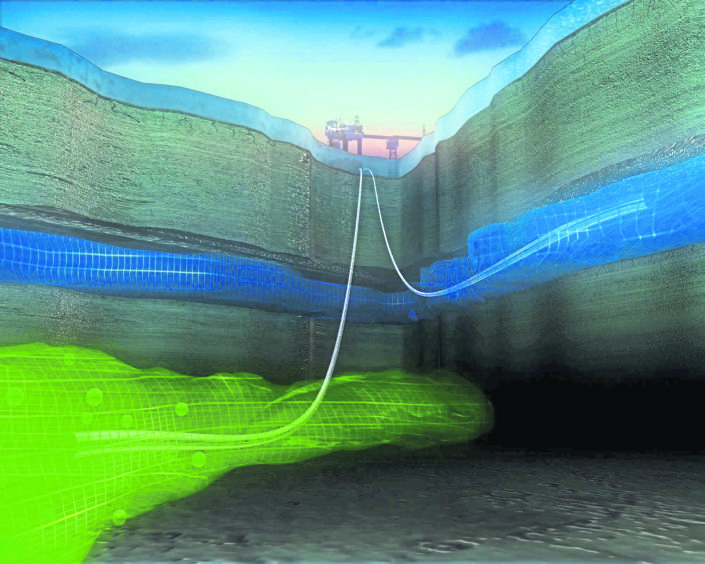

The re-use consultation notes that a CO2 transport and storage network is “central to deploying CCUS” but “requires large upfront capital expenditure”.

The re-use of oil and gas assets is thought to have the potential to significantly reduce such expenditure.

In the UK, re-usable oil and gas assets are largely owned by traditional oil and gas companies. Accordingly, the re-use of such infrastructure will require collaboration between traditional oil and gas companies and CCUS.

While re-use opportunities for offshore platforms and wells are more limited, pipelines are thought to be where the real opportunity for re-use lies.

The Goldeneye, Atlantic and Cromarty, Miller and Hamilton pipelines are specifically identified in the consultation as “infrastructure most likely to have potential for re-use”.

Considering CCUS along with the possibility of re-using oil and gas infrastructure, potential opportunities for traditional upstream oil and gas companies include:

1. Lowering their emissions from natural gas production.

2. Reducing the environmental impact of natural gas production generally, enabling it to remain part of the energy mix for longer than might otherwise be acceptable.

3. Providing an additional revenue stream by offering a CCUS service to customers.

4. Deferring, offsetting and passing-on liability for decommissioning any infrastructure re-used.

Re-use will help support the UK in reaching its net-zero target through accelerating delivery times and lowering the capital investment required for CCUS projects. Re-use for CCUS can offer a win-win scenario.

But things are never quite as simple as they seem. The re-use consultation identifies three factors. Its authors said:

1. The decommissioning of those assets may already have been planned for and scheduled.

2. Essential ongoing monitoring and maintenance costs would need to be incurred during the period between cessation of oil and gas production and CCUS re-use.

3. Under the existing legislative regime, the Secretary of State can require previous owners and operators to decommission oil and gas assets.

A key proposal of the consultation is to give the Secretary of State discretionary power to relieve operators from decommissioning liability for assets which have been transferred to a CCUS project.

That power would only be exercised if the total liability the UK Government may face is no greater than the total liability prior to the transfer of the assets.

It can be anticipated that the Secretary of State may be cautious in transferring decommissioning liability to the CCUS industry.

Accordingly, responsibility for decommissioning may remain as an issue to be resolved on a case by case basis.

The potential of residual decommissioning liability is invariably a concern for oil and gas asset owners transferring assets to other participants.

One potential further enabler would be if the oil and gas companies who own and operate the relevant infrastructure participate in the transportation and storage elements of CCUS projects.

These companies understand the infrastructure and the likely storage sites. If the economics and risks can be shared effectively, CCUS may become a real and interesting part of the energy transition

story.

Recommended for you