It has long intrigued me that, throughout the Second World War, the ground was being laid for the work of the North of Scotland Hydro Electric Board. Even in the darkest days of battle, people and politics were looking to a better future.

The Hydro-Electric Development (Scotland) Act was passed at Westminster in August 1943 and the first chairman appointed by Tom Johnston was Lord Airlie.

He was a major Scottish landowner but one who had expressed the belief that only the state could achieve the objectives of the legislation.

While war rumbled on, the infant board faced bitter opposition from less enlightened gentry through one public inquiry after another.

Pressured by fellow landowners, Lord Airlie insisted what he was doing was “for the greater public good”, a stance which won few friends in the House of Lords.

These were days of big visions and politicians to match, none more so than Johnston, who, at the end of the war, switched from his role as Secretary of State for Scotland to chairmanship of the board.

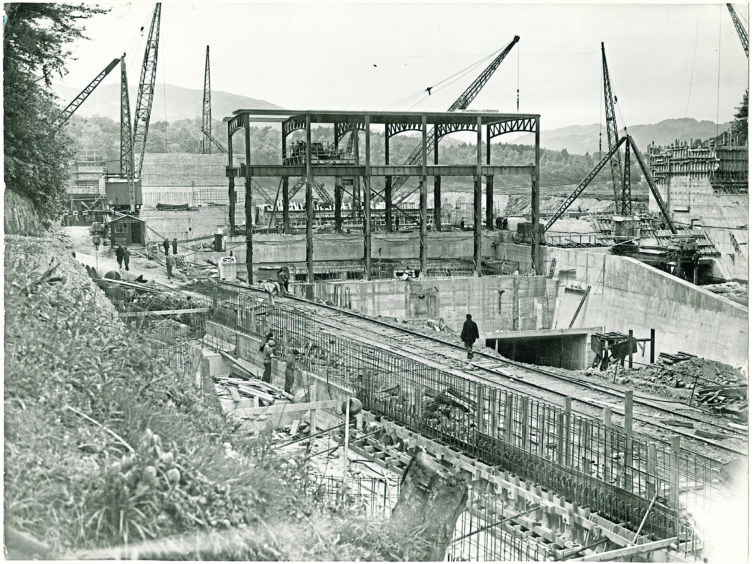

Thereafter, he drove the expansion of hydro schemes throughout the north of Scotland, to its massive social and economic benefit.

In the foreword to his devastating critique of Scottish land ownership, Our Noble Families, Johnston wrote: “It is impossible to comprehend the present or mould the future without first understanding the past.” These are words with great relevance to the dire situation in which we now find ourselves.

There are huge differences between pandemic and war but the common ground lies in the fact that we are going to emerge with a shattered economy, huge unemployment and mountains of public debt. The question is: Can we apply the lessons of history to current circumstances?

Now as then, energy has a huge part to play in any potential recovery. Hydro-electricity combined two great social purposes – bringing power to the most remote corners of the Highlands and islands while creating post-war employment on an industrial scale.

All these decades on, that legacy survives and contributes to our economy and environment.

Once again, major energy projects and innovations have the potential to drag us out of recession, but it will need determined political leadership to deliver them. Does it exist?

There is also, once again, a dual purpose. Not only would there be immediate economic benefits, but serious inroads could be made into the other great imperative of our age – carbon reduction and the fight against climate change.

What planning, I wonder, is being done? In 1943, there were a handful of politicians and public servants who were committed to laying the ground for what lay ahead.

Today, Scotland has innumerable politicians and it would be interesting to know what their big ideas are for the post-pandemic economy?

The same question applies for the UK as a whole and this is an area in which Whitehall and the devolved administrations should already be in close and constructive discussions.

Investment in Scottish renewables is overwhelmingly dependent on the English market, so we need an urgent, joined-up approach to what can be delivered.

We need rigorous measures to ensure maximum levels of work from offshore projects stay in the UK.

We need to unlock Pumped Storage Hydro to create thousands of jobs and also the storage capacity necessary to support the transition to renewables.

We need investment in hydrogen, energy efficiency, basically everything that can create green jobs.

As the oil and gas sector faces massive challenges, the need to link its extraordinary expertise in technology to other energy sectors is no longer an optional extra but an urgent necessity. All of this should be self-evident but each element cannot be seen in isolation. We need political leadership and a sense of mission.

I am not sure if it is inspiring or depressing to find that this is exactly the scale of approach which is being adopted by the European Union – inspiring if we can be part of it, or at least emulate it; depressing if we are isolated and incapable of responding with this scale of vision.

The European Commission is planning to hold 15 gigawatt of renewable energy tenders worth 25 billion euros over the next two years, while a further 10bn will be available to increase member states’ own renewables projects, specifically as part of the post-Covid response. Further tens of billions are earmarked for hydrogen infrastructure.

This “green recovery” strategy was set out by the Commission at the end of May – which means that thinking has been going on along these lines even while the pandemic has been in full swing across Europe.

Is there any parallel groundwork going on in London or Edinburgh which will allow for a grand strategy to emerge?

It may be a cliche to say that every crisis presents an opportunity but it certainly applies in this case.

Either we will address the post-Covid economic wreckage with a series of half-baked measures that will have no lasting impact, or else the opportunity can be seized to deliver something of massive benefit to both our economy and environment.

We have heard a lot of wartime analogies in recent weeks and

most of them are pretty dubious.

In the north of Scotland, however, there is one which is entirely appropriate.

If we could plan for our energy future while fighting for a better world in 1943, the same scale of 2020 vision should not be impossible.

But who is to be our Tom Johnston?

Brian Wilson is a former UK energy minister

Recommended for you