Joe Biden will take office with something no U.S. president has had before: robust popular support for climate action, borne out in polling data and election results from a hard-fought campaign.

“His mandate to go all in on climate change and clean energy could not be more clear,” said Edward Maibach, director of the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication.

Global warming was on the ballot, to a surprising degree. Biden promised to embrace international climate diplomacy and spend more than $2 trillion backing clean energy and green jobs. That created a stark contrast with President Donald Trump’s record of supporting the coal industry, rolling back environmental regulations and withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement. A divide over science and fossil fuel came up in presidential debates and campaign ads.

In the end, Biden won more votes than any other candidate in U.S. history. Final results are still being tabulated, but so far his margin of victory over Trump in the popular vote is around 4 million. That doesn’t mean Biden will be able to to make good on his climate priorities, many of which could be thwarted by Republicans in the U.S. Senate. Control of the chamber will be decided by two contests in Georgia, to be decided in January.

In public remarks on Friday night, while results from key battleground states put the former vice president on the cusp of victory, Biden described the vote as a greenlight for his agenda. “They’ve given us a clear mandate for actions on Covid, the economy, climate change, systematic racism,” he said.

Exit polls appear to show that his messages on climate broke through with voters. Morning Consult found that 74% of Biden voters described climate change as “very important” to their vote, a sign that lack of action would potentially affect the new president’s base. Another exit poll by Fox News and the Associated Press determined that 67% of voters—not just those who cast ballots for Biden—supported “increasing government spending on green and renewable energy.”

That’s the policy Biden put at the center of his economic agenda. Back in July, after emerging as the presumptive Democratic nominee, he came out with an ambitious climate-and-jobs plan that proposed, among other things, to move the country to 100% clean electricity by 2035. Rhetoric linking climate and jobs became a fixture of Biden’s stump speeches. Even before the race had been called in his favor, his campaign’s transition website went live with a brief message that listed climate change as one of four core issues facing the country.

Pre-election polls showed broad support for climate-friendly policies, and in a few cases voters got to weigh in directly. Voters in the the battleground state of Nevada passed a ballot question requiring utilities get half of their electricity from renewable sources by 2030. The measure won 57% support, making it more popular than either presidential candidate.

At the end of September, as the long presidential race entered the final stretch, researchers from Yale University and George Mason University worked with Climate Nexus, an environmental group, on a poll of 2,000 registered voters. The pollsters asked how likely respondents would be to vote for a candidate who required “electric utility companies in the U.S. to generate 100% of their electricity from clean energy sources” by 2035—a summary of Biden’s main climate priority. Two-thirds said that policy would make them more likely to vote for the candidate.

The presidential debates repeatedly took up the issue of fracking, a method of oil and gas production that’s driven the U.S. energy boom. Sparing over fracking in key battleground states came as a surprise to Jon Krosnick, a Stanford University professor who has led polls on climate policies over more than two decades. “There’s this idea that somehow Pennsylvanians would want there to be fracking, but it doesn’t resonate with voters,” he said. “Endorsing it is absolutely not the way to win the electoral college.”

While measures to put limits on fracking and move away from coal are painted as controversial by both politicians and the media, public-opinion surveys routinely show most Americans support the shift towards renewable energy. More than half of U.S. states have adopted renewable targets for their utilities, and solar and wind energy are now cheaper than coal and natural gas in many parts of the country.

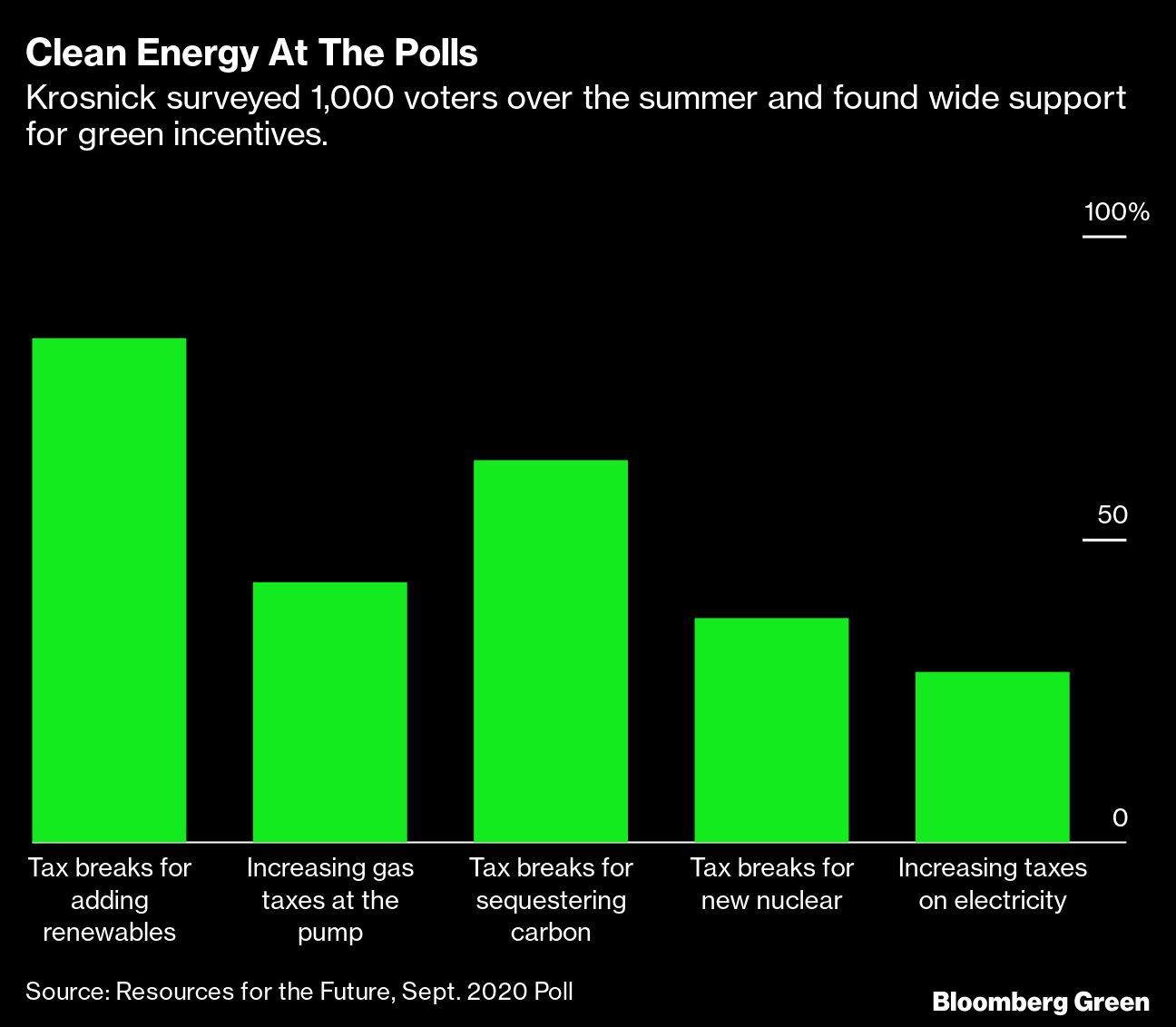

There’s evidence that Biden will find popular support for measures meant to encourage investment in renewable power. Krosnick’s recent surveys found that Americans are overwhelmingly in favor of government incentives to build more wind, solar and hydroelectric capacity. More than 80% of those polled favored tax breaks for utilities that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These policies could end up blocked by a Republican majority in the Senate.

Public support appears to extend beyond a cleaner electric grid. The Yale and George Mason survey found 71% of voters support legislation “eliminating fossil fuel emissions from the transportation, electricity, buildings, industry, and agricultural sectors in the United States by the year 2050,” another key aspect of Biden’s plan.

While Krosnick didn’t test Biden’s policies in his polls, he did find that 75% of Americans favor stronger energy efficiency standards for new buildings, and 71% favor stricter standards for cars and appliances. Trump presided over reduced energy efficiency standards.

The public-opinion data on climate preferences do have some red flags. Biden didn’t embrace a carbon tax during the campaign—and that’s a good thing, according to Data for Progress, a progressive think tank that tested aspects of Biden’s plan in four battleground states over the summer. The group found that just a quarter of voters wanted to put a price on carbon-dioxide emissions, while 55% supported stronger standards and increased investment in clean energy.

Taxes and fees on consumers, as opposed to measures that target businesses, received little support in polls. Krosnick said that less than a third of respondents support taxing consumers for buying fossil fuel-based electricity, even if such a tax resulted lower usage

And, of course, Biden faces a potentially crippling constraint on climate-oriented legislation if his Democratic allies don’t control the Senate. Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale program, said that even within those constraints the new president will enter the White House with “an enormous amount of runway to enact a bold climate agenda.”

Some voters might favor an unprecedented presidential move: declaring that global warming is national emergency. “There’s even strong support among Democrats and independents for that,” Leiserowitz said. “Now it is time for him to put the pedal to the metal.”

Recommended for you