Africa will not increase electricity access and limit carbon emissions, a new study has reported, undermining hopes for a potential “leapfrog” effect.

A University of Oxford study has projected that, in 2030, power supply will have increased by 269 GW, double 2019’s capacity. Bringing power to more people in the continent will be primarily driven by fossil fuel projects.

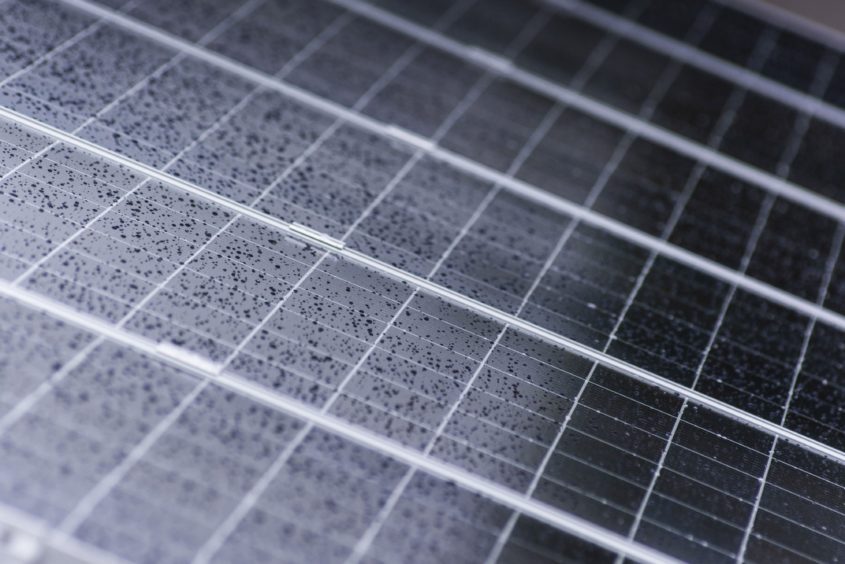

Renewable energy projects, excluding hydropower, will account for 17.4% of installed capacity and 9.6% of generation. Fossil fuel projects will account for 62% of the total and half of all newly commissioned capacity.

The study analysed a database of past and planned projects, using a machine-learning tool to forecast which projects would succeed – or fail.

“There’s a large access gap in Africa, with growing energy demand and abundant resources,” lead author Galina Alova told Energy Voice. “Falling clean technology prices present a unique opportunity to skip the carbon-intensive development stage. We can close that energy access gap and meet needs through renewable energies.”

Despite high hopes for the continent’s leapfrogging of carbon emissions, reality is falling short.

“Even if all the projects we looked at were successful, which will not be the case, there are still not enough projects in the pipeline. There’s too many fossil fuel plans, a much higher share of renewable energy is needed. Those fossil fuel plans need to be cancelled and replaced with renewables,” Alova said.

The study also examined what factors were the most important in determining success for a project. The Oxford study found that it was project specific issues that dictated success or failure, rather than country level. Alova did note that all issues identified were important.

Factors of success

“An enabling environment does matter, but it may be slower to change. It is probably easier to tweak a project parameters to increase the chance of success than wait for governance progress,” she said.

The five most important variables were at the plant level, the study found. These are plant capacity, fuel, grid connection, ownership and the participation of development finance institutions (DFI).

Solar plants have become increasingly successful, for instance, while coal or wind has become increasingly negative. Coal has a predicted failure rate of 34%, while hydropower has the lowest of all fuel sources, at 39%.

The Oxford study provided alternative decarbonisation trajectories.

To drive the level of change sought, all planned coal and oil-fired plants would need to be cancelled and a third of gas fired plants. It would also require earlier than planned retirement of oil and coal as a generating fuel in existing plants. To make up for this shortfall, the supply of renewable energy would need to be nearly doubled.

Alova called for DFIs to pull out of fossil fuels entirely and focus on renewable energy. Additionally, planners should design projects to have a better chance of success.

“Changes in the policy environment would be needed to penalise carbon, through carbon pricing and the removal of fossil fuel subsidies. It requires large-scale changes. We are seeing a gradual transition but it’s not a fast leap forwards. What we need is systemic change.”

Recommended for you