The US administration has set out plans to cut financing for hydrocarbon developments, while African states are doing what they can to secure energy projects.

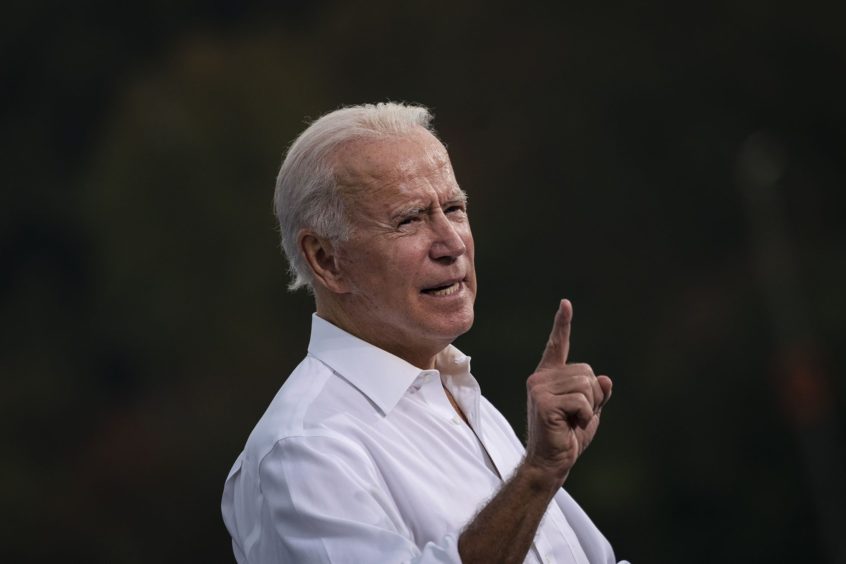

US President Joe Biden hosted the Leaders’ Summit on Climate, with the US publishing its own International Climate Finance Plan.

As demonstration of the seriousness of the US’ commitments, the International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) announced senior appointments on May 10 focused on climate. The agency now has a chief climate officer and deputy chief climate officer, of Jake Levine and Aparna Shrivastava respectively.

DFC aims to reach net zero emissions by 2040 and increase climate-focused investments by 33% in 2023.

Tackling financing

The White House has said US agencies would “seek to end international investments in and support for carbon intensive fossil fuel-based energy projects”. It allowed there may be some limited circumstances under which there was a “compelling development or national security reason” for support to continue.

The US will work with international partners to phase out fossil fuel subsidies.

The proposal also called for other OECD states to reorient financing away from support for “carbon-intensive activities”.

US environmental NGO Natural Resources Defense Council (NDRC) suggested various ways in which this might manifest. The group called for renewable energy to become the base case.

For fossil fuel projects to win support, it said, they would have to prove cost competitive over their lifespan. NDRC forecast that renewable energy projects was already competitive in the majority of cases and would extend this lead in the next five to 10 years.

Friends of the Earth US’ Kate DeAngelis has noted the new policy does not include the US Export-Import Bank. EXIM has provided $5 billion to fossil fuel plans in the last two years, the NGO said.

LNG marketing

One potential challenge is in whether the US administration can continue to seek out new markets for its LNG. The previous administration was eager to link the country’s geopolitical desires with an aim to find new homes for gas exports.

“Loopholes built on finding escape valves for the surplus of U.S. gas should not be tolerated,” the NDRC said.

Nikkei has reported that the US has called for Japan to stop financing LNG-to-power plans, particularly in Asia. Japan’s LNG imports are falling and the country is facing a future where it has over contracted supplies.

As such, supplying the financing for new LNG consumption elsewhere is an attractive play for Tokyo and Japan’s power players.

Japan has not been receptive to the idea. Should the US continue to pursue its own diplomatic endeavours to secure new LNG markets, this would clearly undermine its bargaining position.

Export finance pressure

The US’ plans match similar initiatives taken by the European Investment Bank (EIB) and UK Export Finance (UKEF).

The EIB has said it will not finance fossil fuel projects after the end of 2021. The organisation’s vice president Andrew McDowell said the bank would end financing “of unabated fossil fuel projects, including gas, from the end of 2021”.

Speaking at the beginning of the year, EIB president Werner Hoyer said: “To put it mildly, gas is over … The future does not lie in fossil fuels anymore.”

A group of seven European states made a commitment in April to increase support for sustainable projects and end support for coal. The Export Finance for Future (E3F) coalition was somewhat cooler on oil and gas, though.

French Minister for Economy, Finance and Recovery Bruno Le Maire said the countries would “assess how to best phase out export finance support to oil and gas industries”.

While there does appear to be some wiggle room, few state-backed European lenders are explicit in supporting gas. One of the exceptions is Norway’s Norfund, which has talked of the importance of the resource, particularly for local power generation in Africa.

On the up

Some African states are ready to benefit from the international plans to tackle carbon emissions.

Congo Kinshasa, for instance, aims to capture investments in trees to offset emissions.

Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi has called for higher prices to be paid. Rather than the current $5 per tonne, the president has said prices should rise to $100 per tonne.

The current state of affairs is not enough to reach the Paris Agreement goals Tshisekedi told the Biden’s summit in April.

“A fair price for forest carbon that incorporates foregone opportunities should be at least $100 per tonne. It is important that the [leaders summit] accelerates the mobilisation of additional financial resources and these should be substantial,” he was reported as saying by IHS Markit.

Kinshasa is aiming to plant 1 billion trees by 2023, the report continued.

The US launched the Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest Finance (LEAF) initiative at the summit. The project aims to raise $1 billion to protect tropical forests.

LEAF has issued a call for proposals, with the aim of signing contracts by the end of the year.

Another beneficiary is likely to be Namibia and Botswana. The US has set out a “Mega Solar” plan for the two, which involves the construction of 2-5 GW of capacity.

Switching

Some sub-Saharan African states are making a concerted push in this direction. Kenya, for instance, has a target of 100% clean energy by 2030.

“We cannot win this fight against climate change unless we globally co-operate to fight it together. We cannot wait for future tipping points,” said Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta. The president was speaking at Biden’s climate change meeting.

Kenyatta highlighted the appeal of geothermal power in the East African state. The country also has wind potential, as highlighted by the Lake Turkana project.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa also took the opportunity of the US summit to highlight green energy plans.

The country’s Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) set the goal of achieving 17 GW of electricity by 2030. Ramaphosa said a “just transition” involved reducing the reliance on fossil fuels and emissions. This must come, he said, with “sustaining economic growth, creating jobs and protecting those most affected by these changes”.

South Africa requires an energy shift “where the uptake of sustainable systems and technologies proceeds at a realistic pace”.

Nigeria also took a slightly different stance on the question of the energy transition. The West African state’s President Muhammadu Buhari commended the Biden administration for its efforts on tackling climate change.

Nigeria is cutting emissions, 45% conditionally by 2030, Buhari said, but is also working on ways to improve cooking fuel. This will involve shifting from the use of wood stoves to kerosene, LPG, biogas and electricity.

While some African states are working on a transition, and may even benefit from such a shift, for traditional hydrocarbon producers there are major challenges ahead.