The discussion around clean energy for Africa has tended to focus on solar and wind, with criticism linked to their inconstancy.

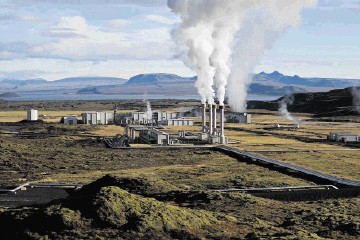

What has received little love thus far is geothermal. Stellae Energy’s David Hartell has called for a re-evaluation of this subsurface resource.

“There are benefits to geothermal over solar and wind. Geothermal is baseload, it just sits there and makes power. It can be adjusted, up or down, providing more or less power as is needed,” Hartell said.

The true cost of geothermal power is competitive – or cheaper – than solar or wind, he continued. Intermittency problems disguise the true cost of solar and wind, which batteries or other generation must compensate.

Of particular interest, Hartell said, was the new breed of geothermal resources.

Historically, the energy has required high temperatures to generate power. As a result, “high enthalpy” developments have focused on the East African rift, such as Kenya, and Iceland.

Lower power

Modern technologies require lower temperatures, Hartell explained, opening up new areas capable of producing power. The binary Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) turbine allows geothermal resources of as low temperatures as 100-200 degrees Celsius to generate electricity, down from 250-300 degrees.

There may be “tens of thousands” of sites that could generate power, he said. The process involves the circulation of a fluid through the hot rock or reservoir. This then drives a turbine.

“The technology is readily available. It can range from 100 kW to 10s of megawatts,” Hartell said.

The Stellae Energy executive said his research suggested 25 countries in Africa may be suitable for such developments.

He is in conversation with interested parties in Nigeria, Cameroon and Ghana. Companies working in remote regions, such as miners, are particularly interested, Hartell said.

Such a geothermal project offers cost savings when compared with running operations on diesel, which is often the default fuel.

Drilling pivot

“Africa has the resources and the companies and the expertise,” he said. Oil and gas companies can pivot to this geothermal resource as an additional business stream.

“One of the biggest cost elements [in geothermal] is the well, which may account for 30-40% of a project’s costs. If oil and gas wells can be repurposed, that can be a massive saving.”

Costs are already coming down, he continued, going on to estimate that the price tag for generation may be around $2-3 million per MW. A project will run for 20-30 years, he said.

Geothermal power could act as a complement to oil and gas developments, Hartell said. Generating electricity from the binary ORC process would allow exports of hydrocarbons to continue, rather than seeing those consumed domestically.

Furthermore, while there are funding challenges for oil and gas, there is a “lot more” available to renewable energy.

Hartell said he had held conversations with various funders who were excited about geothermal plans. “It’s a clean renewable, persistent energy source addressing energy poverty – it checks a lot of boxes.”

Perhaps the greatest challenge to rolling out geothermal plans are a lack of regulation. Few areas have specific laws set out for the resource. Often, rules established for oil and gas developments are used to oversee the work.

As with any drilling, there are some concerns around earthquakes, but Hartell was unconcerned. “It’s not a big risk,” he said. “Before going ahead with a development, you would data work. Then drill a 600 metre borehole and then a deeper hole. That derisks spending money and provides insights into the next phase. That would allow you to identify risks ahead of time.”

Recommended for you