Leaders of the Group of 20 countries agreed on a climate deal that fell well short of what some nations were pushing for, leaving it to negotiators at the COP26 summit in Glasgow this week to try to achieve a breakthrough.

“It is easy to suggest difficult things. It is very difficult to actually execute them,” Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, the summit’s host, told reporters in a briefing Sunday. “What the G-20 countries have done today is a step forward in a long and difficult transition. We don’t know yet what the final goalpost of this transition will be.”

The final communique after two days of intense negotiations in Rome agreed to phasing out investment in new offshore coal power plants by the end of 2021. On domestic coal, it contained only a general pledge to support those countries that commit to “phasing out investment in new unabated coal power generation capacity to do so as soon as possible.”

The document mirrors prior pledges made in the 2015 Paris climate accord, saying nations remain committed “to hold the global average temperature increase well below 2 degrees Celsius and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.”

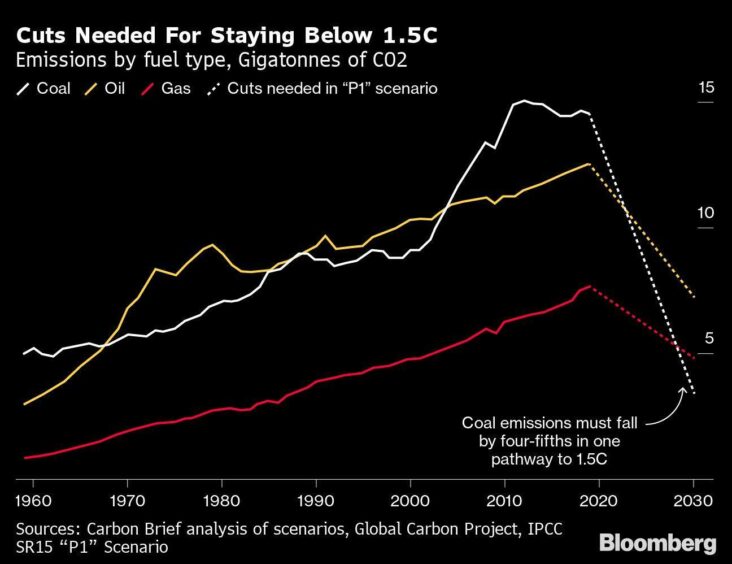

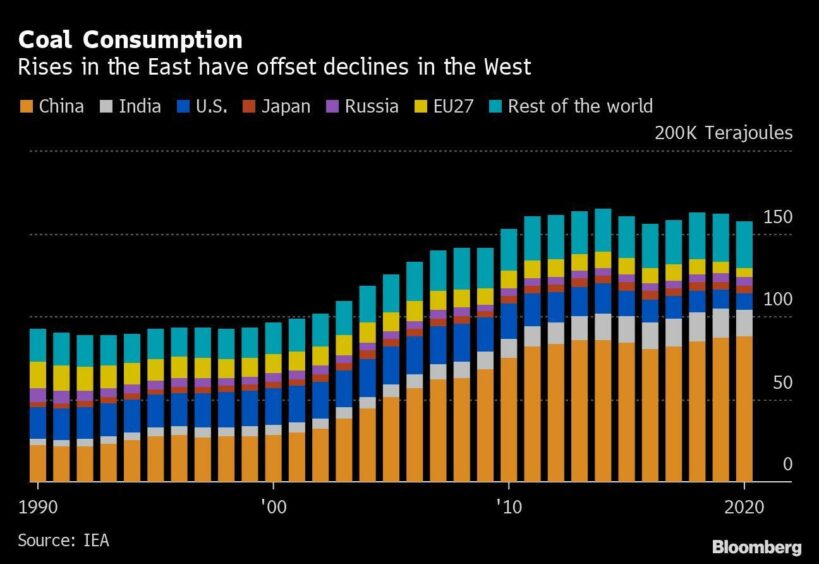

While COP26’s UK hosts had aimed to “consign coal to history,” many nations remain deeply dependent on burning the fuel that represents the biggest single obstacle to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees. The energy crisis has underscored the importance of secure supplies and driven up coal prices amid a shortage of natural gas. China is pressing coal producers to increase output to ease shortages. India burns more coal than Europe and the US combined to produce about 70% of its electricity.

The G-20 made some progress but “there is a huge way still to go,” UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson told reporters. The target of 1.5 degrees is “very much in the balance. Currently we are not going to hit it. We have to be honest with ourselves.”

Discussions over the past week produced continuous clashes over both objectives and timelines on climate, with several officials pointing the finger at holdouts China, Russia and India. The last round of talks saw negotiators known as sherpas talk throughout Saturday night, ending their marathon with applause at the main La Nuvola venue at about 10 a.m.

The sherpas “achieved a good signal for Glasgow,” Angela Merkel told reporters at the end of her final G-20 summit appearance as German chancellor. “The fact that everybody agreed on the 2 degree goal from Paris and that the 1.5 degrees must be within reach is a very, very good result.”

Still, divisions were on display over the date for achieving net-zero carbon emissions, with the communique saying only that it would be “by or around mid-century,” rather than by the 2050 deadline pledged by the Group of Seven nations at their June summit.

The G-7 states in Rome “negotiated the draft declaration first and then decided to circulate it to others” with 2050 included, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, whose country has set 2060 as its target, told reporters.

“It is not very polite to use this negotiating process the way the G-7 tried to,” Lavrov said. “Nobody has proven to us or anybody else that 2050 is something which everyone must subscribe to.”

The communique’s language “is a bit more toward 2050,” Draghi said. “I am confident that we will gradually get toward a 2050 commitment.”

The statement offered little in the way of concrete action. It committed to “significantly reduce” greenhouse gas emissions “taking into account national circumstances.” Much of the wording, including references to national circumstances and a circular carbon economy, were favored by countries including Australia, China, India and Saudi Arabia.

“If the G-20 was a dress rehearsal for COP26, then world leaders fluffed their lines,” said Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International. “Their communique was weak, lacking both ambition and vision, and simply failed to meet the moment.”

The summit rowed back on commitments in earlier draft statements to phase out domestic coal use. A version on Thursday seen by Bloomberg contained a pledge to “do our utmost to avoid building new unabated coal power generation capacity.” Saturday’s draft pushed that to “in the 2030s.”

The outcome of the talks is disappointing on both overall climate ambition and coal power, and stands in stark contrast to the G-7 summit, according to BloombergNEF head of global policy Victoria Cuming. “At the G-20 event, it appears that they need to devote time to explaining why the 1.5 degrees target is important,” she said.

In other key climate questions:

- The leaders agreed to be “vigilant of the evolution of energy markets”, a reference to surging prices for oil, natural gas and coal that have rocked much of Europe and Asia. The G-20 said it was key to ensure “affordability” of energy.

- They reaffirmed a commitment to support the green transition in developing countries by jointly mobilising $100 billion annually through 2025.

- The final text no longer has tangible commitments to cut methane emissions, which was in earlier drafts. It now only acknowledges that methane emissions are a significant contribution to climate change.

- The communique recognises the efforts of some countries to ensure at least 30% of global oceans and seas are conserved or protected by 2030 but only encourages others to make similarly ambitious commitments.