Nuclear power once seemed like the world’s best hope for a carbon-neutral future. After decades of cost-overruns, public protests and disasters elsewhere, China has emerged as the world’s last great believer, with plans to generate an eye-popping amount of nuclear energy, quickly and at relatively low cost.

China has over the course of the year revealed the extensive scope of its plans for nuclear, an ambition with new resonance given the global energy crisis and the calls for action coming out of the COP26 Climate Summit in Glasgow. The world’s biggest emitter, China’s planning at least 150 new reactors in the next 15 years, more than the rest of the world has built in the past 35. The effort could cost as much as $440 billion; as early as the middle of this decade, the country will surpass the US as the world’s largest generator of nuclear power.

China’s Catching Up

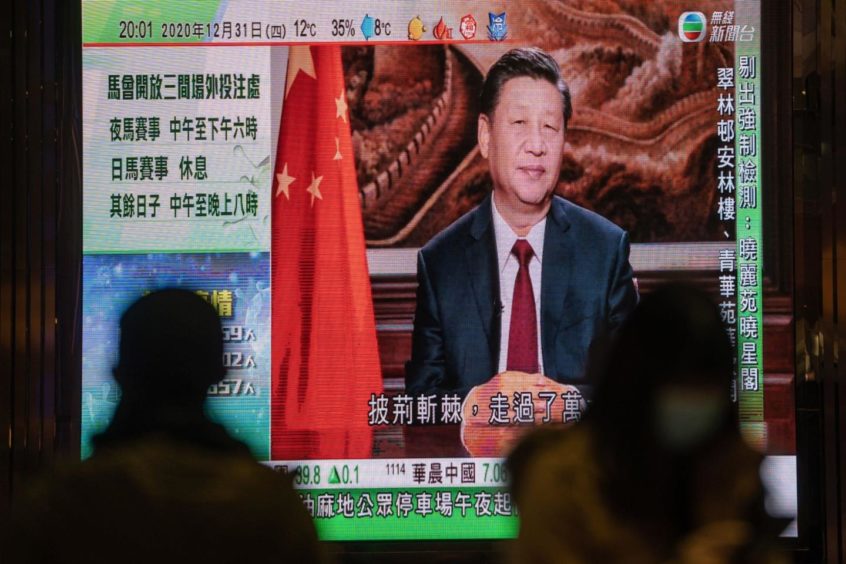

The government’s never been shy about its interest in nuclear, along with renewable sources of energy, as part of President Xi Jinping’s goal to make China’s economy carbon-neutral by mid-century. But earlier this year, the government singled out atomic power as the only energy form with specific interim targets in its official five-year plan. Shortly after, the chairman of the state-backed China General Nuclear Power Corp. articulated the longer-term goal: 200 gigawatts by 2035, enough to power more than a dozen cities the size of Beijing.

It would be the kind of wholesale energy transformation that Western democracies — with budget constraints, political will and public opinion to consider — can only dream of. It could also support China’s goal to export its technology to the developing world and beyond, buoyed by an energy crunch that’s highlighted the fragility of other kinds of power sources. Slower winds and low rainfall have led to lower-than-expected supply from Europe’s dams and wind farms, worsening the crisis, and expensive coal and natural gas have led to power curbs at factories in China and India. Yet nuclear power plants have remained stalwart.

“Nuclear is the one energy source that came out of this looking like a champion,” said David Fishman, an energy consultant with The Lantau Group. “It generated the whole time, it was clean, the price didn’t change. If the case for nuclear power wasn’t already strong, it’s a lot stronger now.”

China says its plans could prevent about 1.5 billion tons of annual carbon emissions, more than what’s generated by the UK, Spain, France and Germany combined. For those who see nuclear power as critical to weaning off planet-warming fuels like coal, it’s a wildly exciting experiment at a scale proportional to the problem.

And yet, even if China can develop the world’s most cost-effective, safe, flexible nuclear reactors, the US, India and Europe are unlikely to welcome their biggest global adversary into their power supplies. CGN has been on a US government blacklist since 2019 for allegedly stealing military technology. In July, the UK began looking for ways to exclude CGN from its Sizewell reactor development. Iain Duncan Smith, Tory Member of Parliament, put it bluntly: “Nuclear is critical to our electric power, and we just can’t trust the Chinese.”

China’s ultimate plan is to replace nearly all of its 2,990 coal-fired generators with clean energy by 2060. To make that a reality, wind and solar will become dominant in the nation’s energy mix. Nuclear power, which is more expensive but also more reliable, will be a close third, according to an assessment last year from researchers at Tsinghua University.

Other countries would have to stretch to afford even a fraction of China’s investments. But about 70% of the cost of Chinese reactors are covered by loans from state-backed banks, at far lower rates than other nations can secure, said Francois Morin, China director at the World Nuclear Association.

That makes a huge difference because most of the cost of atomic energy is in upfront construction. At 1.4% interest, about the minimum for infrastructure projects in places like China or Russia, nuclear power costs about $42 per megawatt-hour, far cheaper than coal and natural gas in many places. At a 10% rate, at the high end of the spectrum in developed economies, the cost of nuclear power shoots up to $97, more expensive than everything else.

“People say nuclear is expensive in the West, but they forget to say it’s expensive because of interest rates,” Morin said.

China keeps the exact costs a state secret, but analysts including BloombergNEF and the World Nuclear Association estimate China can build plants for about $2,500 to $3,000 per kilowatt, about one-third of the cost of recent projects in the US and France.

The 2035 goal of an additional 147 gigawatts would cost between $370 billion and $440 billion, a potential windfall for investors in CGN Power Co., China National Nuclear Power Co., and China Nuclear Engineering & Construction Corp. As it is, shares in listed units of all three state-owned companies are up between 19% and 43% since August, compared with a 2.3% drop in Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index.

China also expects its domestic projects to persuade potential overseas buyers. In 2019, the former chairman of China National Nuclear Corp. said China could build 30 overseas reactors that could earn Chinese firms $145 billion by 2030 through its Belt and Road Initiative.

Its most eager customer has been Pakistan which, like China, shares a sometimes violently contested border with India. China’s built five nuclear reactors there since 1993, including one that came online this year and another expected to be completed next year.

Other countries have been more hesitant. Romania last year cancelled a deal for two reactors with CGN and opted to work with the US instead. A 2015 agreement with Argentina has been stalled by economic upheaval and changes in the country’s leadership. Memorandums of understanding to build reactors with countries including Kenya and Egypt have yet to develop into anything concrete.

Along with the potential for geopolitical fallout, potential partners have other concerns. China hasn’t signed on to any of several international treaties that set standards for sharing liability in the event of accidents. It also hasn’t offered to take back spent fuel, an added disadvantage when competing with Russia, which does.

Still, versions of China’s first homegrown reactor design, known as Hualong One, continue to operate safely in Karachi and Fujian province. And in September, China announced a successful test of a new, modular reactor that could be enticing overseas. China Huaneng Group Co. said it had achieved sustained nuclear reactions in a domestically designed, 200-megawatt reactor that heats helium, not water. By making the cooling process independent of external power sources, it should prevent the potential for the kind of massive meltdown that required the evacuation of more than 150,000 people in Fukushima.

China’s modular reactors, if successful, wouldn’t require new power plant construction. In theory, they could replace coal-fired generators in existing thermal power plants, according to Morin at the World Nuclear Association.

“The world needs more flexible supply options,” said Prakash Sharma, a Singapore-based analyst at energy research firm Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “The advantage of a small modular reactor is that you can fit them better into the overall power supply.”

China’s willingness to help fund projects and share expertise has also helped its argument, said Chris Gadomski, an analyst with BloombergNEF. “With nuclear, China is stepping up to the plate with financing,” he said.

Prior to the meltdown at Fukushima, China’s nuclear goals were even bigger. Within a week of the tsunami that triggered a meltdown at the Japanese atomic plant, the Chinese government put a moratorium on new projects and began a deep safety review of its entire program. By 2014, it decided against building any more reactors that required active safety measures, like the one at Fukushima did. It paused approvals again for several years until it was satisfied with its new technology.

Fukushima, Chernobyl, Three-Mile Island: Each new disaster underscores the most obvious risk in nuclear energy. Plants house incredibly dangerous radioactive material — even after 10 years of cooling, spent fuel can release twenty times the fatal dose of radiation in one hour. And in the event of a leak or an explosion, the potential for immediate and long-term damage is enormous. In Chernobyl, 350,000 people had to be evacuated after an explosion shot radioactive material into the atmosphere, and dozens of workers died of radiation poisoning within weeks. More than 30 years later, there are still reports of dangerously high levels of radiation in locally produced milk and grain.

Scientists say the technology has improved, and so far, the longer-term effects of the meltdown at Fukushima have been less severe than many feared. But public support for nuclear power has waned to the point that new investment is politically untenable in most democracies. At COP26, applications by the International Atomic Energy Agency and industry advocates to set up shop at a more public and visible area were rejected. Japan’s efforts to restart its fleet are mired in court actions and public opposition, Germany will take the last of its reactors offline next year, and France has pledged to cut its reliance on nuclear energy from 70% to 50% by 2035.

Beijing’s own record was largely spotless until June, when reports emerged of an issue at the French-designed plant in Taishan. Any report of a problem at a nuclear plant is alarming, let alone one at a facility within 100 miles of both Hong Kong and Shenzhen.

The incident underscored the potential problem with big nuclear projects, and how they can be made worse by Chinese firms’ typical lack of transparency or public accountability. While media reports and rumours swirled about a possible problem at the plant, CGN insisted everything was fine. Its partner, the French utility EDF, wasn’t so sure, and eventually took its case to the public as a way to push for more information, at one point alerting the US government.

It took weeks before Chinese officials clarified that the problem involved a few damaged fuel rods, which is common and in this case, experts agreed, unthreatening. The plant was eventually shut for maintenance, which EDF said would have happened as a matter of course in France.

While the incident ended up being largely uneventful, it widened the already gaping trust gap between China and the global marketplace for nuclear technology. China’s business practices are often opaque and sometimes downright hostile to the world’s other big emitters. The US, India and others are unlikely to build critical infrastructure around Chinese technology, even if it does prove safe and cost-effective.

“China is a gigantic part of our economic life and will be for a long time—for our lifetimes,” UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in an October interview with Bloomberg Editor-in-Chief John Micklethwait. “But that does not mean that we should be naïve in the way we look at our critical national infrastructure.”

Chinese firms are welcome to invest in non-strategic parts of the economy, but Johnson refused to say what he’d define as “strategic.” It’s clear, though, that the line has moved in a short period of time.

In 2016, China’s CGN invested in three UK reactor developments, part of an effort to upgrade an ageing nuclear fleet. Now, even as the country confronts a potentially crippling energy crisis this winter, government officials are trying to minimise CGN’s involvement in one of the projects and buy out its stake in the other two.

Crisis or no, it’s hard to see the country move actively toward more nuclear now, given the country’s fraught relationship with China, said Michal Meidan, director of the China Energy Research Programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “The lack of transparency and concerns about working relationships have become deeper,” she said.

Recommended for you