The ScotWind offshore wind programme has been hailed as an unprecedented boon for Scotland and the UK, providing jobs, cash and infrastructure – but how do government and industry ensure these local benefits are delivered?

Seventy-four bids have been submitted by companies and consortia looking to secure awards in the 10-gigawatt (GW) ScotWind offshore wind leasing round. Many have promised billions of pounds of investment and thousands of jobs in Scotland if they make good on their bids.

Orsted, for example, has identified £12 billion of potential investment across its five bids, while BP and partner EnBW have promised a £10bn spending package if successful.

For now, however, these are promises rather than contractual commitments – leading to fears that some may never be delivered.

Unions have pointed to the 2010 Scottish Government Low Carbon Economic Strategy for Scotland report which predicted 28,000 direct jobs in offshore wind for Scotland as the industry kicked off; in the end, less than 2,000 direct jobs in Scotland were delivered over the period.

Progress has been made in recent years. As part of the Offshore Wind Sector Deal, the industry as a whole has committed to a voluntary target of 60% lifetime UK content in domestic projects, (up from the current 50%) by 2030, and said it would seek to increase the amount of UK content in capital expenditure.

Hopes are high that ScotWind will see developers make good on those ambitions, with many bidders making explicit their early engagement with local supply chains.

To that end, the Crown Estate Scotland (CES) has asked bidders to prepare a Supply Chain Development Statement (SCDS) as part of the leasing process, with applicants required to produce information on how and where their supply chain expenditure will be spent.

These are broken down into different project stages (development, manufacturing and fabrication, installation and operations) and across different locations (Scotland, rest of UK, EU and elsewhere) – through crucially there are no minimum requirements for each.

Bidders also supply a separate list of “ambition” figures, which show the upside of what they consider achievable in each category.

These SCDS documents can be revised in collaboration with the CES as the project moves forward, to ensure the developer – and the supply chain – is able to move with the market.

“Developers have the chance to evolve their supply chains prior to the point at which legal consequences apply, and can therefore respond to market developments provided they comply with the procedural requirements,” noted Keith Patterson, a partner at Brodies LLP.

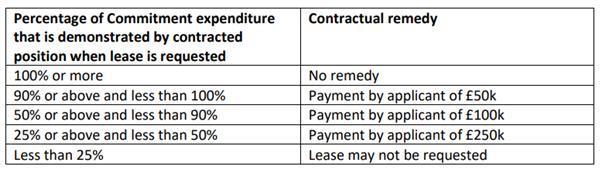

Once in development, bidders then set out the actual expenditure incurred and/or covered by finalised contracts in a contracted position statement (CPS). Failure to match their updated SCDS with committed CPS contracts will result in financial penalties, based on how far commitments fall short. Those who are severely short are unlikely to be awarded seabed leases.

“The contractual remedies in the option are designed to ensure that the developer is incentivised to achieve the commitments they make,” noted Burness Paull partner Neil Bruce.

“The upshot of this is that the developer will have to be realistic about what it is committing to do, and pay close attention to how achievable that is.”

Even so, as Mr Patterson adds: “Crown Estate Scotland intends to impose fines for deviation from the last updated supply chain development plan. However, it has been quite clear that it cannot legally require developers to comply with these plans.”

Contracts for Difference

Separate to CES’ leasing process, projects must also be formally consented to sell power via the UK government’s Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme, for which there are similar supply chain requirements.

Antony Skinner, energy partner at law firm Ashurst, explained that as of the recently opened fourth CfD allocation round (AR4), a bidder’s supply chain plans must be formally assessed and approved by the Secretary of State prior to construction, in order to be granted a CfD.

“This is significant because a project can’t start to receive payments until it has satisfied the operational conditions precedent – and ultimately if this is not satisfied by the longstop date under the CfD, then the CfD will be terminated,” he added.

ScotWind: ‘A very clear commitment’

Gary Bills, country director and managing director for UK and Ireland at renewables consultancy K2, concedes that without a firmer framework from government, the industry’s 60% UK content commitments are not binding.

“Without legislating for a very strict requirement, it’s difficult to see how this will hold together,” he explained.

However, he remained optimistic about the public headline statements made by some of the major ScotWind bidders.

“I would caveat that by saying some developers have made very specific commitments to invest X amount of pounds in X facility. That’s pretty hard to get out of – even if there’s a very small penalty and the reward is better [not to use local resources], it’s a very clear commitment that you’ve made, and I think that would be honoured.”

Paul O’Brien, head of the DeepWind supply chain cluster made a similar point in a recent interview with Energy Voice: “The public announcements from many of the developers and consortia involved in the ScotWind bid represent a significant comment to the Scottish supply chain… Why do we think these pledges will be met by successful applicants? It will be very difficult for these companies to go back on what has been very public statements of intent.”

Instead, Mr Bills said that developers’ intentions to use the UK supply chain and workforce – as set out in SCDS documents and public statements – may well be “differentiators” in the bidding process, rather than minimum requirements.

Those who over-promise and under-deliver may therefore be judged unfavourably – even if there were no legal implications.

“If you’re someone heavily invested in the Scottish economy, I think irrespective of the penalties or the lack of penalties, the reputational damage and the knock-on effects that may come from that would be too damaging,” he added.

Keeping promises

The extent to which the Scottish supply chain could be used will also depend in part on its ability to adapt to provide services to the burgeoning floating wind market.

Sir Jim McDonald, who recently produced a Scottish Offshore Wind Energy Council report on the need for port “clusters” to work together to deliver this, told Energy Voice there has been “convergence” between the “government, industry and prospectively the investment community” to deliver that.

In the context of the significant amount of capacity planned, Neil Bruce argued that flexibility in supply chain procurement should be viewed positively.

“As I understand it, one of the reasons for having the SCDS is so that the different developers involved over the different zones, the Government and CES can look closely at the work required in order to help the Scottish supply chain develop and grow to maximise so far as possible the expenditure from projects in Scotland,” he added.

In that regard, the awards may see some developers commit more to local economies than others to ensure all 10GW is delivered – but the rising tide of offshore wind development would lift all boats.

But, cautioned Mr Bills, it’s important for the whole sector that developers ensure their pledges are kept.

“It is a huge opportunity and irrespective of whether these companies do or don’t [succeed], we really need to keep them on the hook for the promises they have made,” he said.

“As an industry, we need to keep them on the hook for their promises.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by SSE

© Supplied by SSE © Supplied by Crown Estate Scotlan

© Supplied by Crown Estate Scotlan © Supplied by Siemens Gamesa

© Supplied by Siemens Gamesa