Shell engineer Denise Neill knows as well as anyone in Aberdeen, the UK’s oil capital, that the fortunes of a city that gets its income from one source can change quickly.

The daughter of a farmer, she witnessed in the 1970s how the discovery of North Sea oil transformed the lives of local people, including her father who switched to selling rock from a quarry on his land for the expansion of the city’s airport.

“You had a lot of people suddenly going into businesses they’d never worked in before and within a very short space of time,” Neill, 55, said from Shell’s Scottish headquarters in the city.

Now as a deputy project manager for two giant floating offshore wind farm developments, she’s at the forefront of another transition that could make or break the Granite City.

Oil prices may be booming again, but growing demand for cheap home-grown energy as Russia’s war in Ukraine squeezes supplies is giving Aberdeen another reason to shift its focus to renewables.

In the process, the city is constantly finding itself beholden to the will of politicians in Westminster and Edinburgh who regularly use the energy sector as a pawn in arguments over Scottish independence and keep flip flopping over whether they want to shut down fossil fuel production as soon as possible or keep investing until the transition to renewables is well underway.

Just this year the UK government has switched from begging the industry to invest more in North Sea oil and gas in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, to slapping a three-year windfall tax on those same companies’ profits as energy prices surged.

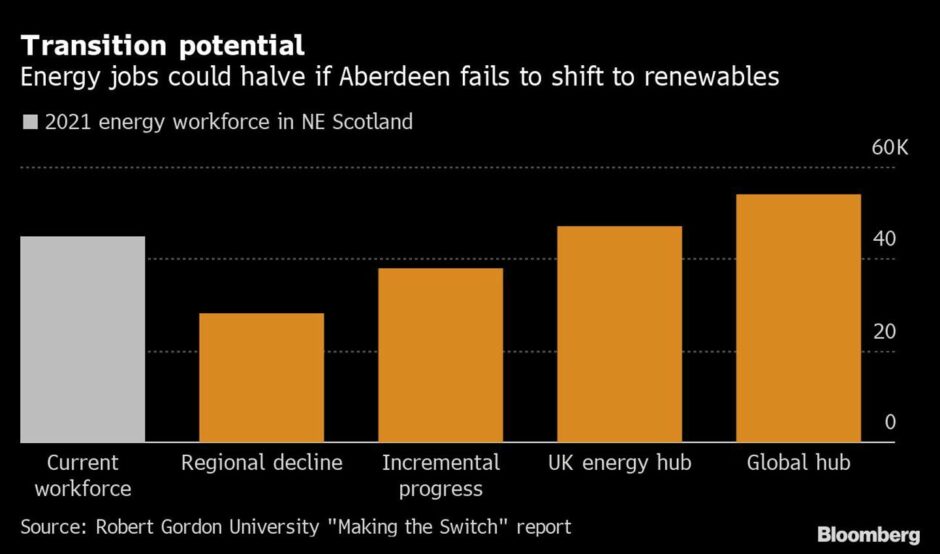

Decades of declining North Sea oil production and back-to-back price crashes in recent years have given residents a taste of what the future holds if they don’t make the transition.

Even with oil near $100 a barrel, Union Street, the city’s main thoroughfare, is dotted with boarded up shops and restaurants.

Dan Andreson, co-owner of nearby Contour Cafe says business is down about 50% since before the pandemic because many clients worked at energy firms which have laid people off.

The city wants to turn the tide on that trend by leveraging its decades of experience in complex energy projects to turn itself into a renewables hub for the UK or even Europe.

Get it right and it could hold on to its status as one of the richest cities in the UK. Get it wrong and that oil wealth could depart as quickly as it arrived.

It’s a challenge faced by oil towns everywhere as governments seek to switch to clean energy and cut dependence on Russian oil and gas without creating a surge in unemployment from jobs linked to fossil fuels.

Aberdeen needs only to look 150 miles south to Glasgow for a reminder of what happens when a town’s main source of income is yanked away too quickly. Once one of the ship-building centers of the world, the city was for many years synonymous with unemployment and rampant crime as yards moved east in the 1960s.

The oil and gas sector has seeped into all parts of life in the city of just under a quarter of a million. The 1.5-hour Monday morning flight from London is packed full of industry folk shuttling up for the week or the day who all seem to know each other.

One in five people in Aberdeen and the surrounding area works in the sector, according to research by the Energy Transition Institute at local Robert Gordon University. That rises to one in three if you include jobs in industries that support it, such as taxis, hotels and catering.

The government in Westminster wants to ramp up renewables production at the expense of fossil fuels in order to reach its target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and Scotland’s devolved parliament is planning for the shift to happen five years sooner north of the border.

“There’s always been a direct correlation between the oil price and Aberdeen happiness,” says Paul de Leeuw, director of the Energy Transition Institute. “That has changed. People realize it’s a different world. Everything is shifting given what we need to do with the energy transition.”

In theory the shift to renewables should be fairly straightforward for Aberdeen. Its coastal location in the far northeast of Scotland makes it a perfect jumping point for offshore wind and its population is already well versed in engineering and services connected to the energy sector.

The transition to wind production in Aberdeen is already well underway, although most of the projects won’t come online until 2030 or later. The Scottish government issued licenses earlier this year for projects to develop 25 gigawatts of power, equivalent to about half of the UK’s wind target for 2030. Two thirds of the permits are for wind fields that are within 100 nautical miles of Aberdeen.

Oil majors BP Plc and Shell, working together with power companies, were among the winners of the tenders and are using technology usually reserved for building oil platforms to install wind turbine foundations in the seabed off the Scottish coast.

The city is hoping to soak up the bulk of the logistics and service jobs connected to the farms, like it did with the oil rigs in the past. A new harbor has been added to the Port of Aberdeen with more space for the large vessels required to build and service offshore wind.

Near the harbor, Ian Wood, former head of Aberdeen-based oil services firm John Wood Group Plc, is chairing an industry-backed project called the Energy Transition Zone, which aims to create a manufacturing cluster to serve low-carbon industries.

“Having massive oil and gas reserves off our shores was a massive stroke of luck,” said Wood, who is one of Scotland’s richest people. “I hope we’re going to have a big stroke of luck again.”

Less certain is the city’s ambition to capture the bulk of the UK’s hydrogen production, partly because the sector is still in its infancy. The UK is aiming to reach 10 gigawatts of installed hydrogen production capacity by the end of the decade, and Scotland has its own target to get to 25 gigawatts by 2045.

To produce hydrogen in large quantities, you need a power supply, which needs to come from renewables if the UK is to meet its net zero targets. So Aberdeen’s close proximity to offshore wind farms could help it be a major player in the sector.

So far the city is showcasing the fuel’s potential via a fleet of 15 hydrogen-powered busses and a joint venture with BP aims to build a refuelling facility that will produce over 800 kilograms of green hydrogen, enough to power 50 large vehicles. The plan is to scale up production later for use in rail, freight and marine transport, heating and potentially for export.

If it works out, hydrogen could provide a major source of new jobs. Currently the oil and gas sector supports about 90% of the energy workforce in northeastern Scotland, according to De Leeuw at the Energy Transition Institute. He estimates that most of those workers have “medium to high transferability” from the fossil fuel to the renewable sector, while about 10% will struggle to find work if oil and gas dries up in the region completely.

Richard Haydock, who leads BP’s offshore wind projects in the region, says about half of his team come from fossil fuel production. He made the shift after a long career working on oil and gas projects around the world because he was attracted by the challenge of creating huge wind farms from scratch.

Shell’s Neill, who spent three decades working on some of the biggest hydrocarbon developments in the world before changing to wind, says most of her team has a background working in oil and gas and found it relatively easy to make the transition, though there’s a lot to learn.

She sees similarities between the growth of the renewable sector now and the oil boom that was creating jobs in the region when she was a chemical engineering student at Edinburgh University in the 1980s.

“If I was a graduate in today’s world, I would be excited to see the kind of opportunities that we’re creating,” Neill said. “We created a global oil and gas industry and I think we can do the same in renewables.”

Recommended for you