As the UK aims to reach net zero by 2050 we will see more and more wells decommissioned both on and offshore; geothermal specialist CeraPhi believes it can use some of this infrastructure to heat buildings and power installations across the country.

The Great Yarmouth-based firm believes that by using existing decommissioned wells and its closed-loop geothermal system, heating can be provided to a range of building types at a stable cost as the world experiences a cost of living crisis with the fluctuating price of oil and gas.

Despite making headlines with its partnership with Petrofac and EnQuest on the Magnus platform the geothermal company’s primary focus is onshore.

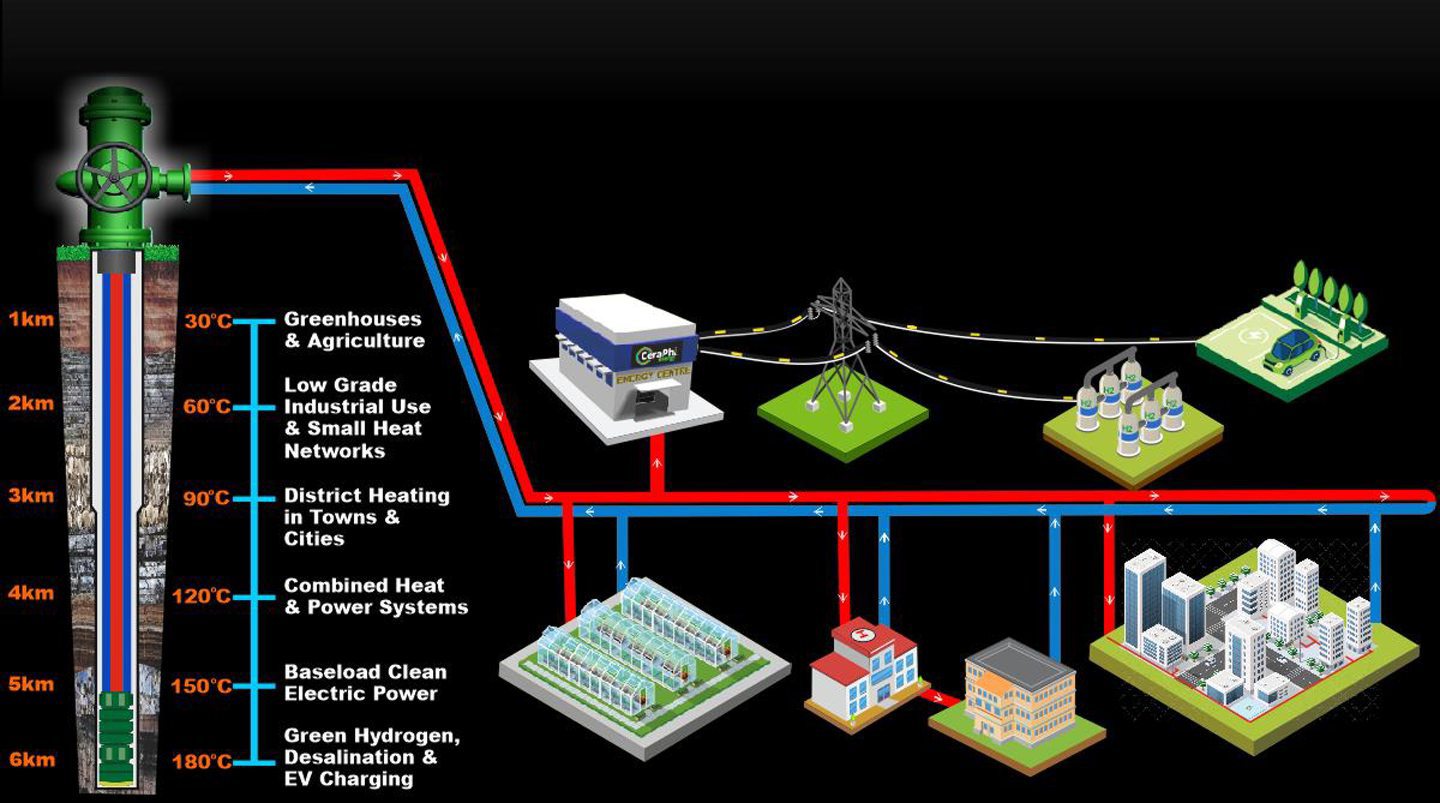

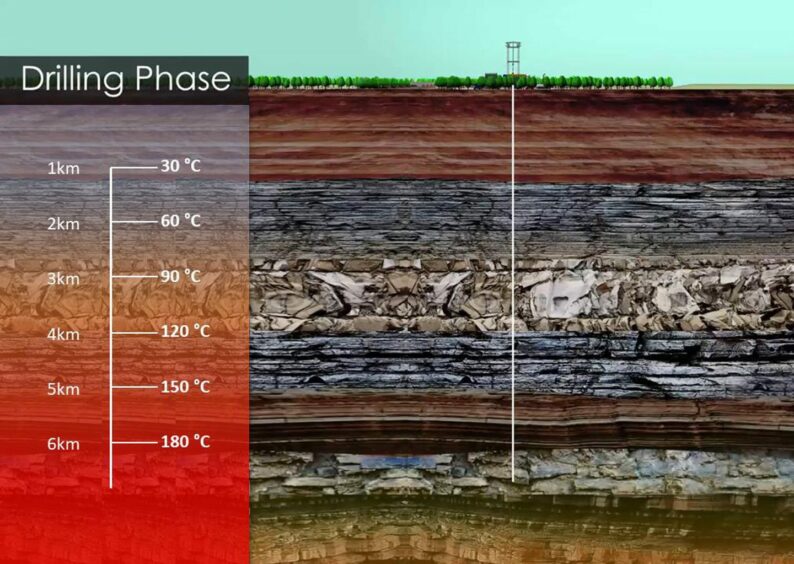

Geothermal is a type of renewable energy taken from the heat that comes from the earth’s subsurface, contained within rocks and fluids.

Gary Williams, the firm’s co-founder and chief operations officer told Energy Voice: “Probably 90% of what we’re doing as a business is looking at onshore geothermal developments, be it repurposing existing assets from the fossil fuels industry or drilling new wells using the fossil fuel industry. ”

Chief executive Karl Farrow added: “In the UK we are in a sort of onshore side of depletion like we are offshore.

“Onshore, I think there are still some 600 plus wells in the UK that probably, on average, could produce half a thermal megawatt each, some more, some maybe a little bit less, but even there you’ve got 300 megawatts of potentially usable energy, which is 10s of thousands of homes of potential usage.”

Farrow explained how this company can use the decommissioning process to gain extra value from wells at the end of their lifespan: “When we repurpose on a well – and I think this has been quite an important thing for people to understand – you’re already going into an element of decommissioning.”

The geothermal company planw on providing geothermal infrastructure for hospitals.

One hospital that the firm spoke to claimed to have spent “nearly £900,000” on gas bills for heating in 2021.

According to Williams: “We could put a geothermal system in there and based on what they’ll be paying for gas now, which is probably double, they could recoup that cost for the geothermal system in about 5 years.”

The CeraPhi co-founder says that having its own well will also allow a hospital (or any large-scale building that has purchased a well) to sell heat produced at the site to nearby hotels, entertainment centres and homes as they are built around the space.

The logistics of providing geothermal heat to new buildings, such as housing developments, is no more difficult than fitting gas boiler infrastructure to a home, said CeraPhi’s chief operating officer.

“Say you’re building 1000 houses” Williams said, “20 years ago you’d think nothing of putting a gas pipe into each house.”

“What you would now want to do is have your same type of pipework going into the house, so the approach is no different, except instead of bringing gas, you’re just having a geothermal well somewhere nearby feeding directly into that and you’ve got absolute control of cost there.”

The focus of this project is on new builds as Williams told Energy Voice, “It’s more of a challenge retrofitting existing systems.”

“Putting it in is part of the planned development of new projects, so new housing, new hospitals, it’s a lot easier then because you factor that in as they develop.”

Less heat is required while keeping homes and hospitals warm

Mr Farrow explained that geothermal systems heating homes are more energy efficient.

He explained that historically heat sources come from producing high temperatures, something that CeraPhi claims is not an issue when using geothermal energy.

“The historic way that heat networks have been built is primarily on waste heat recovery, so heat coming from a power plant or some sort of coal plant or something like that, even in Eastern Europe and places like that,” Farrow said.

“They’re only obviously taking that waste heat at the temperature they receive it, so it’s always been quite high, like 80 to 90 degrees.

“So historically heat systems and heat networks have been built on high-temperature feedstock coming from fossil fuels.

“Whereas the next generation of heating that we’re now looking at is what they call low-temperature systems, which don’t need that high temperature.

To produce room-temperature heating, CearPhi will only have to drill wells of one or two kilometres (a maximum of 1.2 miles) in depth.

CeraPhi: trading ‘space-age’ tech for existing equipment

Speaking on how their company was founded, just over two years ago, Gary Williams told us how his partnership with fellow co-founder Karl Farrow came about.

“So we’ve known each other in the industry doing different things for 20 years. We’ve worked close to each other alongside each other but never worked together directly and the other guys that founded the business with us,” Williams said.

Being laid off from a research and development firm based in Bratislava after the Covid-19 pandemic forced the company to downsize, which is when Williams and Farrow came to a realisation.

“Whilst their idea of plasma drilling and all sorts of space-age stuff was great, we kind of proved to ourselves that there was actually a viable business based around a different approach to geothermal using existing technologies and equipment, but in a different way,” Williams said.

Farrow added: “We sort of batted things around for a month or two, then come the 1st of September we kicked off in earnest.

“We’ve grown from there, so there was originally five of us founded, the business. One of the founders had to step away from the business. So this left is the four of us.

“We’ve attracted investors who were keen to see us grow, and they’ve supported our journey so far and we’ve now got to a point where we’ve got around about 30 people working with us.”

The firm went from having four members of staff, the company founders, to 30 in less than two years, Williams told Energy Voice.

The firm’s founders are confident that the company will continue to grow in strength moving forward.

Farrow said: “We have recently signed a multimillion agreement with Halliburton for drilling services globally as an exclusive agreement.

“You know Halliburton aren’t the sort of company to sign an agreement with someone like CeraPhi if they don’t see, there’s a huge potential in that market and there is a huge potential.”

Bringing geothermal energy to North Sea platforms

CeraPhi working on providing geothermal power to EnQuest’s Magnus platform, which Gary Williams, said is still at a “very early stage.”

Mr Williams told Energy Voice: “The first phase of this project is basically just to assess the viability of the wells that they have available at Magnus.

“EnQuest is providing us with the data that we need for the study, our part of the project is to look at the wells and anything below the surface.

“We’ve contracted to work with Petrofac and they are looking at the surface equipment, they are obviously equipment specialists so they’re looking at the service infrastructure that would go on the platform.”

The UK-based geothermal firm signed a deal with Petrofac earlier this year and Jonathan Carpenter, vice president at Petrofac New Energy Services, said the study “could be a game changer” in decarbonising oil and gas assets.

CeraPhi does not plan on powering all off the Magnus platform as Williams told us: “It’s just to make a contribution to decarbonising that platform, the primary thing is to see what we can do with the wells.”

If this first stage of the study is successful, the company will get in contact with the Net Zero Technology Center (NZTC) and look to roll out its technology to more North Sea operators to “develop a wider plan” where the geothermal company will look to “help individual platforms and maybe create networks” between platforms.

Karl Farrow said the goal of phase one is “to understand the framework of parameters around working on the offshore environment”, looking into weather conditions and environment.

Mr Farrow later explained the future ambitions of the project, saying: “What we can do going forward is, if we were to design wells to be able to produce hydrocarbons whilst producing geothermal energy to then be able to use that to power platforms and infrastructure in the future to be totally independent, a sort of stand-alone and be completely decarbonised.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by CeraPhi

© Supplied by CeraPhi © Supplied by CeraPhi

© Supplied by CeraPhi © Supplied by CeraPhi Energy

© Supplied by CeraPhi Energy © Supplied by CeraPhi

© Supplied by CeraPhi © Supplied by EnQuest

© Supplied by EnQuest