Set in the heart of the unforgiving North Atlantic Ocean, some 175 miles away from its nearest neighbour, Iceland is on the front line of efforts to collar climate change, in all senses.

Internationally renowned for its stunning landscapes and sprawling glaciers – now at risk due to increasing temperatures – the island nation has some of the most ambitious net zero targets in the world, setting a pace for others to follow.

By 2030, Iceland wants to have cut its emissions by 40%, with the ultimate aim of zeroing them out altogether before 2040.

Sat in a small room in the beautiful capital city of Reykjavik, Iris Baldursdottir, co-founder of energy systems start-up Snerpa Power, laid out the country’s decarbonisation roadmap.

“Here in Iceland, we have a very renewable power system, and we’re highly electrified, but we still need to go much further,” she told a group of journalists, of which I was one.

“By 2040, we want to be carbon neutral and completely independent of fossil fuels. That means we have to electrify transport on land, sea and air.”

Fortunately, with a geographical leg on either side of the diverging Mid-Atlantic Ridge fault line, Icelanders have a natural renewable energy source right below their feet.

Geothermal energy, generated by the Earth’s core, is used to heat 90% of homes in Iceland, and accounts for around 30% of the electricity supply.

Combined with hydropower, 100% of the nation’s electricity and house-heating needs are met with renewables, or about 90% of its primary energy supply – the rest is plugged by oil and gas imports.

It means Iceland, with its population of about 372,000, claims the top spot as the largest green energy producer per capita in the world.

A power source that is always on

Key to that impressive feat is HS Orka, the country’s largest privately owned power producer.

During a visit to the company’s headquarters at the Svartsengi geothermal plant, on the island’s southern peninsula, we sat down with the Johann Snorri Sigurbergsson, director of business development.

He said: “We drill into the ground, about 2 kilometres down, to harness the heat below us. But, to get the energy that comes with that, you need something to carry it to the surface, so you pump cold water in to fracture the rock. Fluid is then pumped up and, once it reaches the surface, it goes to a separator, where steam and fluid is parted – the steam then powers the turbines, which creates electricity.”

Benefitting from the low carbon, cheap energy produced at Svartsengi, one of HS Orka’s three power plants, are a number of nearby businesses.

Ranging from life sciences to fisheries, they form the basis for the Resource Park, which also includes Iceland’s most popular tourist attraction, the legendary Blue Lagoon – the result of geothermal drilling at the site.

And while we didn’t visit that specific hot spring during our trip – organised by trade group Green by Iceland – there was a tranquil couple of hours spent in Reykjavik’s Sky Lagoon, watching the sun slowly set over the North Atlantic.

Indeed, Iceland’s abundance of low-cost, renewable power has helped to make the country a hotbed (pun intended) for business start-ups, while its modest population means that collaboration – far from being reserved for conference speak – is very much the done thing.

Of course, the UK has geothermal ambitions of its own, with hopes that the Earth’s natural heat can provide a portion of the baseload clean power needed for net zero by 2050.

But as industry leaders pointed out during chats at a Business Iceland mixer on the first night of our visit, what works for Iceland, may not necessarily work for others. Systems that serve a country with roughly the same size population as Stoke-on-Trent are unlikely to translate effortlessly.

Oil and gas skills can be harnessed to generate geothermal

Nevertheless, there is still an opportunity for Iceland to export its skills and knowhow to inform the development of geothermal energy systems elsewhere.

Mr Sigurbergsson said: “Iceland has already exported a lot of its knowledge to different countries with geothermal ambitions. Not so much in the UK just yet, but to the likes of Ethiopia, and other nations that have relatively easy access to this high heat resource.

“You can’t just get it anywhere, you need to find places along tectonic plate lines and I’m pretty sure that if the UK wants to exploit geothermal energy, there are a lot of different companies in Iceland that will be on hand to help.

“When Icelandic experts are sent to conferences or seminars around the world, usually people don’t want to let them go again!”

What the UK does have in its favour, explained Mr Sigurbergsson, is a wealth of geotechnical skills built up in the North Sea, specifically around drilling.

In 2016, Norwegian energy giant Equinor, alongside partners in the Iceland Deep Drilling Project, spudded the world’s hottest geothermal well, and the sector is an area that oil and gas companies are increasingly looking to target.

Mr Sigurbergsson said: “Equinor (OSLO: EQNR) drills 5 miles deep all the time, so this was nothing new for them. There is definitely crossover, and a chance to share learnings between geothermal and oil and gas. That’s the reason why Equinor came into the IDDP partnership.”

Greening geothermal

But while geothermal energy is renewable, it isn’t entirely green.

Naturally occurring carbon dioxide accounts for a minute fraction of production, but it is a fraction that Iceland is working to eradicate.

Local company Carbfix has developed a novel solution that involves dissolving CO2 in water and injecting it into basalt, commonly found across the island.

After a few weeks in the formation, the liquid turns to stone, offering long-term emissions storage – a natural version of carbon capture and storage, if you will.

At the time of writing, since 2014 Carbfix has injected 90,895.8 metric tonnes of CO2 at the Hellisheidi power station, the largest facility of its kind in Iceland that also doubles up as a geothermal energy exhibition.

On a particularly wet, windy and foggy visit to the facility, we took refuge in one of Carbfix’s three injection sites to hear from Olafur Teitur Jonsson, the group’s head of communications and marketing.

He said: “Carbfix isn’t limited to geothermal areas at all. In fact it may even be, in some instances, more favourable and more economical to be in places without such heat. We have been mineralising CO2 here now for a decade, and it is estimated that we have used less than 0.01% of the capacity of the site. The resource is enormous, and theoretically the basalt in Iceland could store all of the CO2 that is emitted by mankind. There are limiting factors, but it’s definitely not the capacity of the rock to receive carbon.”

Carbon transport market

Such a bountiful resource has unsurprisingly caught the eye of nearby countries, and work is ongoing to create the Coda Terminal, a cross-border carbon transport and storage hub.

Small volumes of carbon has already been transport from Switzerland for injection, with further emissions coming from Climeworks’ on-site direct air capture (DAC) technology, which sucks CO2 out of the atmosphere.

And while Carbfix’s system is unique, there are synergies with carbon capture and storage, meaning there is an opportunity to share learnings and experiences.

Edda Sif Pind Aradottir, the firm’s chief executive, said: “It’s the same value chain, but typically you don’t have the depleted oil and gas fields in the same geographical area that we find our sites. The technologies are complimentary because they open up so many more areas around the world where you can inject CO2 for storage.

“We can certainly provide insight for other types of storage, and vice versa – there are definitely things we can learn from CCS projects too. It is all a collaborative effort to get these value chains up and running.

“Carbfix has had a lot of interest from oil and gas companies, as well as other large emitters, including steel and cement.”

During a presentation at Hellisheidi, Ms Aradottir also issued a sobering reminder as to why Iceland is so desperate to be among the first nations across the net zero line.

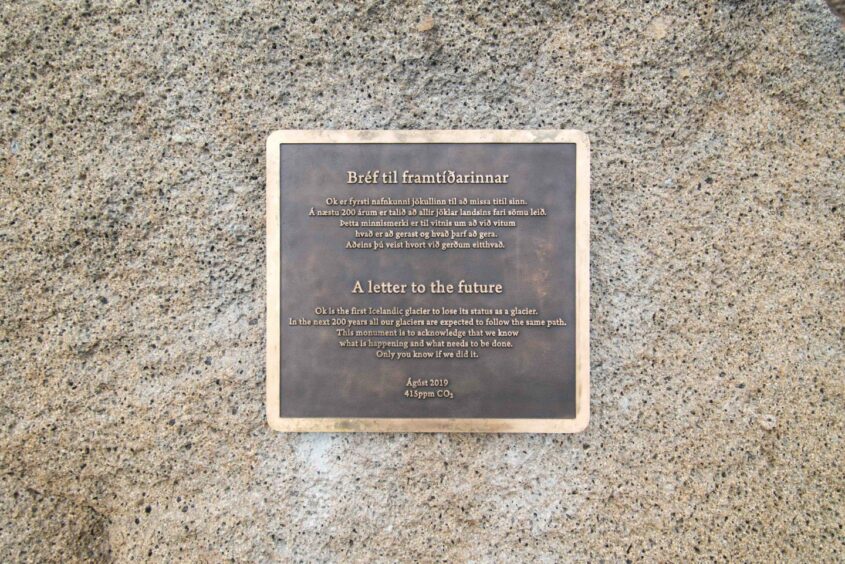

Located north-east of Reykjavik, there is a plaque on the former site of the Ok glacier, which was declared dead by a leading geologist in 2014.

Ok was Iceland’s first glacier to lose its status, and Ms Aradottir says that in the coming decades, all of the nation’s other major ice bodies will go the same way, unless the brakes are put on climate change.

Installed in August 2019, at 415 parts per million, the plaque – fixed to a rock on what now acts as a memorial – is inscribed with a letter to the future.

“Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you will know if we did it.”

Recommended for you

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock © Supplied by HS Orka

© Supplied by HS Orka © Shutterstock / biletskiyevgeniy.

© Shutterstock / biletskiyevgeniy. © Supplied by Equinor

© Supplied by Equinor © Shutterstock

© Shutterstock © Shutterstock / Boris_Niehaus

© Shutterstock / Boris_Niehaus