As oil and gas operators try to tackle emissions on the ground, MethaneSAT aims to locate and quantify them from orbit – with data published for all to see.

Devised by the US-based Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), the satellite’s mission is to both “motivate and enable” the global oil and gas sector to slash methane emissions by 45% by 2025, and 70% by 2030.

Of all methane emitted by human activity, oil and gas operations account for around 38%. And while gas does not linger in the atmosphere as long as CO2, it is more potent, with more than 80 times the warming power in the first 20 years.

If its reduction targets are met, EDF has said it would have a similar climate impact over that 20-year period as closing one-third of the world’s coal plants.

The project – which is aided by Harvard University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory – will monitor at least 80% of global hydrocarbons production, in many cases down to specific sites and assets.

With all data to be made publicly available, it means anyone from governments to investors will be able to see and compare results – by company, country or production basin. A recent New Yorker article likened the system to CCTV for the planet.

MethaneSAT: CCTV for the planet

Despite a year or so of pandemic-related delays, MethaneSAT’s lead chief scientist and EDF senior VP Steven Hamburg says the project is now on track to launch in “early 2024” when it will be sent skyward on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

“We will start collecting data very quickly but it will take a little bit of time until we turn the valve completely open,” he says.

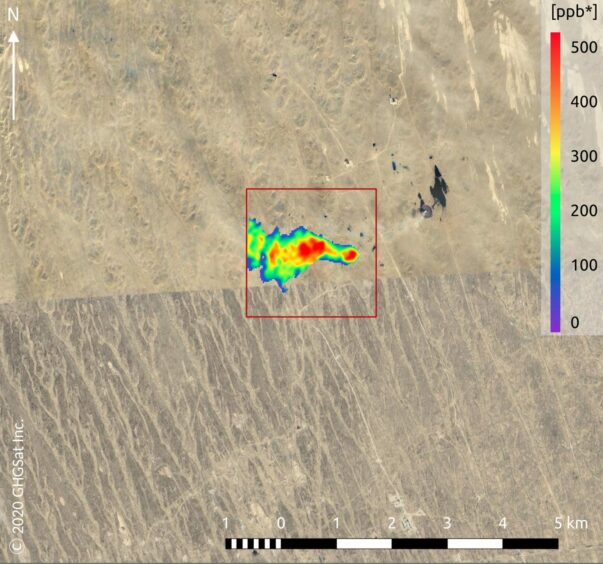

The detail offered by the technology is unprecedented. Using two passive infrared littrow spectrometers, the unit will be capable of detecting excess methane at levels of 3 parts per billion – a level of scale and detail unmatched by other systems launched to date, such as GHGSat or the European Space Agency’s TROPOMI.

In practice, that will enable it to quantify regional methane output sites down to areas of around 1km square, picking up sources down to around 500 kg/hour. At a larger scale, it can aggregate emissions from thousands of smaller sources together, offering a clearer picture than ever before of how much methane is escaping.

Once launched and calibrated, the focus of the satellite is also highly strategic.

“We are looking at targets,” says Mr Hamburg. “Because we have such fine spatial scale and a wide swathe – we have a 200km swathe and a native pixel size of 100m x 400m – we are collecting an enormous amount of data for a 200km line.”

Weather forecasting will be taken into account to ensure each pass is valuable –necessary, he explains, because the capacity of data transfer to the ground is one of the satellite’s main constraints.

“We have identified where we want to look and we look ahead at the weather conditions, and if the weather is not going to be good we don’t bother collecting, because we don’t want to waste that capacity,” he explains.

In the meantime, he says progress is going well.

“The satellite is fully constructed, all the tests are meeting or exceeding the requirements

“We have completed the data platform which for the first time will take all the raw data and calculate concentration and all the flux data on how much is being emitted and where it’s being emitted – so that’s really exciting.”

At present the instruments are being tested on aircraft via sister project MethaneAIR – a feat in itself, which Mr Hamburg says will produce “the first comprehensive map of emissions in North America.”

“We’ll also be testing our data platform and analysis systems so we can wring out any issues so it’s ready to accept and quickly process data from MethaneSAT when it launches,” he adds.

“With a satellite, you’ve got to get it right – you don’t have the option to tweak it later.”

Data open to the public

Elsewhere he says EDF’s data and stakeholder teams are reaching out to stakeholders to make sure users will be able to understand and harness the data posted by the satellite once launched.

This may come in different formats for companies, governments, financial institutions, science, society, he continues.

“They’re all going to be using the data in different ways, so we’ll have multiple products.”

How has the industry reacted to these plans? Mr Hamburg is diplomatic.

“I wont put words in their mouth…but I think there’s awareness of what’s going on and a realisation that we’re about to enter an era of radical transparency, which is a game changer.

“The key here is that these data will be produced – though we’ll be careful to ensure it’s high quality and validated – and it will be open to the public. That’s a whole new world.

“And it will be policy relevant in that we will know how much is being emitted, where it’s being emitted and how much it’s changing over time.”

Regardless of one’s opinion of the project however, it’s clear that many industries will now be held to a higher standard as the pressure to fully decarbonise intensifies. Future phases of the deployment, for example, will include attempts to quantify agricultural emissions too.

“I think we have had a positive reaction, but change is hard,” Mr Hamburg says.

“We’re introducing a whole new level of transparency so I’m sure there will be multiple reactions to it. But for the most part we’ve been talking about this for quite a while so certainly much of the industry and many governments are getting their arms around what will be possible in the near term which was not possible before.”

© Supplied by GHGSat/European Spac

© Supplied by GHGSat/European Spac