DEEP is looking to “revolutionise the way that humanity more broadly accesses, interacts, and ultimately understands the ocean,” the firm’s president Sean Wolpert says.

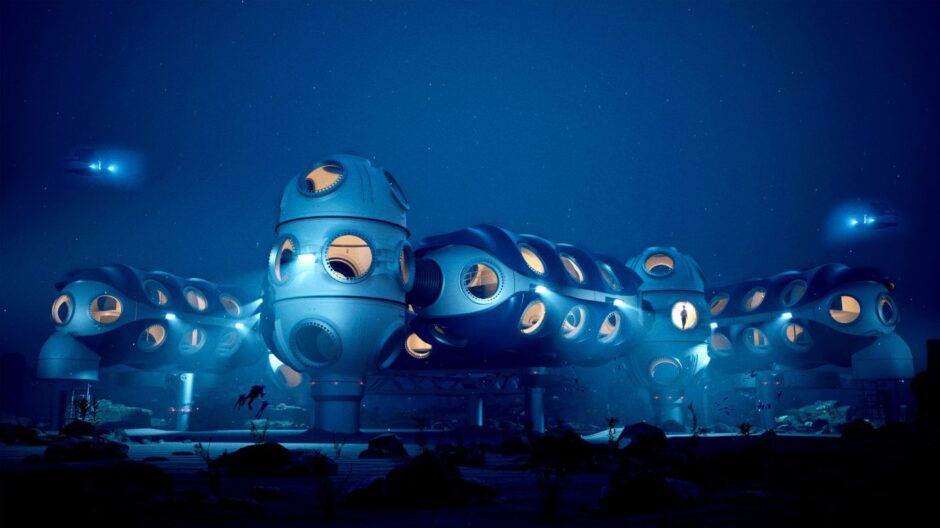

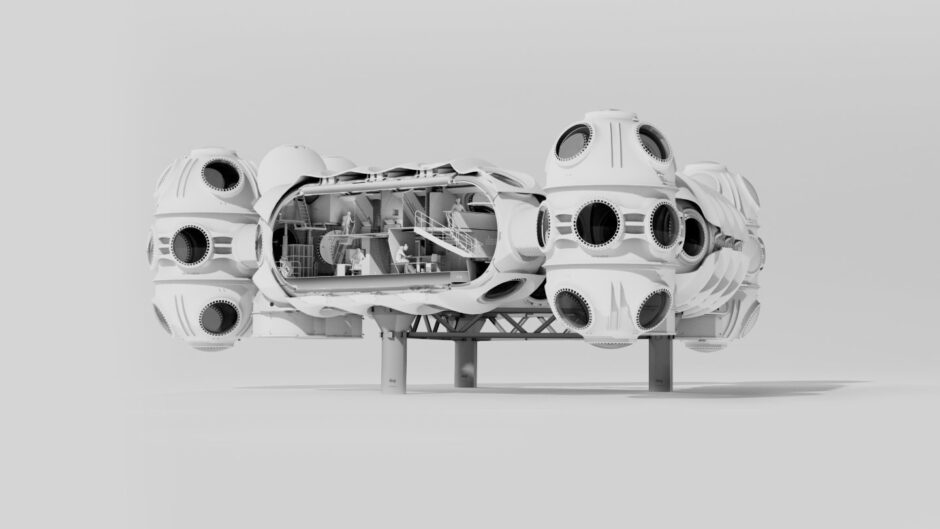

This is where DEEP’s Sentinel research base comes into play. This research facility can be deployed on the sea floor may look like something from a Jules Verne novel but in fact it may become a reality sooner than you’d think.

Mr Wolpert told Energy Voice: “We would expect to have the Sentinel system in place and deployed in the ocean by 2027. So, on this side of this decade.”

When asked if subsea bases, like Sentinel, could support the energy industry the DEEP president said it “absolutely” could.

“If you look at a lot of the work going out with wind farms, you can have this be your central observatory, your central communications hub and maintenance hub.

“You can have that operating envelope in and around that that Sentinel system. That absolutely could be there to support, it can be an ingestion of data having that set of eyes on this to make sure when that’s being deployed, it’s being done properly, observing what that kind of impact is to the local ecosystem as well.”

Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) are often used to carry out this work, providing operators a figurative set of eyes on the ocean floor. However, by having people on site firms can gather more date, Mr Wolpert argues.

“Most of the conventional methods at the moment, whether it’s looking at diving or ROVs and so forth, they’re discrete. You only observe it at that particular point in time.

“But the ocean is a very dynamic system. Having that continuous presence greatly increases the amount of data that you collect, and you understand what the consequences are from those decisions, the longer term for that ecosystem.”

Testing to kick off at the start of 2025

DEEP is aiming to test its system at its quarry site in Chepstow, which used to be the National Dive and Activity Centre. This will take place in the first quarter of next year as DEEP looks to incrementally assess its system.

“Now the key thing here is it’s incremental, right? So, we’re not going to go and build this and go straight to the deepest part possible,” the president of DEEP explained.

“We’ve only mapped about 50%, now why is that?” Sean Wolpert questioned.

“We look up and see the stars and we have that connection, we have that affiliation with it.

“The ocean, we just see that glossy surface, now in the in the oil and gas sector of course they have experience going down there, but the majority of the population around the world has not had that benefit.

“That disconnect means that people don’t truly grasp the understanding of the importance of the ocean to everything we take for granted up here and again, that’s something we’re looking to correct with our habitat system.”

The DEEP president says that what can be found beneath the waves is “out of sight, out of mind” and this is something his team aims to correct.

“It’s not The Four Seasons, but it’s something that creates a much more comfortable type of environment,” he joked.

‘Leaps, not marginal improvements’

Mr Wolpert and the DEEP team were at Subsea Expo at the end of February where the company president took part in the Aberdeen event’s opening plenary session.

Last month Global Underwater Hub’s chief executive, Neil Gordon, likened the technical challenges of the DEEP’s Sentinel research base to “putting people on Mars”.

The Sentinel system is modular, allowing it to be customisable and enabling “short-term through to semi-permanent deployments, anywhere on the Continental Shelf.”

One thing that sets DEEP’s system apart from traditional seabed research bases is that it can be deployed in one location then moved and redeployed in another once operations are complete, and the base is no longer needed.

Mr Wolpert described this feature as “one of the key innovations” of the Sentinel system.

He added: “If you look at what we’ve had before in terms of habitats, they’ve been fixed, they tend to have been quite small, shallow deployments.

“Where we’re looking to have leaps, not marginal improvements, is the Sentinel is deployable to 200 metres [Around 656 feet] and it’s larger. If you cut a Boeing 777 in half, that’s the same interior volume.

“They’re redeployable but they’re not propelled so you can’t turn a key and drive off somewhere else, but you can redeploy it. So, you can fix it in an area of interest for whatever that time frame might be.”

This is something that has created interest with some prospective clients telling the DEEP team “I could do seven days’ worth of work in 30 days if I had access to this type of asset,” Mr Wolpert claimed.

“Then you can remove that [the Sentinel base] and it’s not something that’s a matter of months, this is a matter of weeks of going and finding that next location and redeploying it there.”

The challenges of helium

However, as Mr Wolpert and the team at DEEP aims to make “leaps, not marginal improvements” in existing technology, challenges must be overcome.

“It’s learning how things have been done in the past, the challenges of humans being in saturation, the engineering challenges of putting people down there. These are things that we need to build on and learn from those paths that have been blazed historically,” he added.

In addition to contending with the engineering issues presented by bringing people to the seabed and putting them into saturation, the equipment in the Sentinel base also needs to withstand the pressures.

While in saturation, divers usually breathe a mixture of helium and oxygen to prevent nitrogen narcosis, a side effect of this is they sound chipmunk-like.

DEEP’s president explained: “So there’s big challenges here, particularly when you’re going down in that saturated environment when you have to have mixed gas. For example, when you want to have that fluid access, really being able to kind of access the benefits of that Sentinel system.”

He added: “The way it’s been described to me by our engineers we have, we have at least two dozen engineers and naval architects have been working on this, hyperbaric medical experts and so forth.

“Helium is a very selfish gas where it likes to absorb heat, so if you want to feel like you’re in 20°C you need to heat it to be 30°C.

“Now if you have a 30°C environment with an open moon pool, you’ve just created a rainforest. So, you need to look for those interior systems to be designed to dehumidify.”

Mr Wolpert continued, explaining that helium is also a “slippy gas” and that also presents challenges.

“What you find is if you bring your iPhone down there, for example, and you’re down there for three weeks, it’s not really going to work the same because it interferes with a lot of the instrumentation,” he explained.

“You’re going to run into the same issues with a lot of this equipment as well. One of our key design tenants is to house all of these life support systems, not in a support buoyed surface, but contained within the Sentinel.”

DEEP’s “little over 75 full-time employees” have a lot of work ahead of them to ensure that the Sentinel research base is delivered before 2030, as is intended.

However, Sean Wolpert is confident that DEEP can have its subsea research base in the water on time.

© Supplied by DEEP

© Supplied by DEEP © Supplied by Michal Wachucik/ Abe

© Supplied by Michal Wachucik/ Abe © Supplied by DEEP

© Supplied by DEEP © Supplied by DEEP

© Supplied by DEEP