Industry experts have made a call to action over the “collapse” of geoscience skills in the UK.

Academics say the number of first year undergrads has dropped by “more than 40% in just a few years” despite a requirement for such skills in development of key technologies like offshore wind and carbon capture.

Among recent closures are the petroleum geoscience degree at Imperial College London, while earlier this month Aberdeen University’s department was ordered to trim a third of its staff by next summer as part of wider cuts.

In a new report, the Subsurface Task Force, a not-for-profit group of experts, said the collapse of interest and talent will lead to a skills shortage and knock on challenges for net zero.

The STF said that a director-level civil servant in the UK Government told them recently that they “do not see the benefit” in geoscience to reach net zero, despite the need for such skills in carbon capture, offshore wind, geothermal and nuclear waste sequestration.

STF chair Graham Goffey said the government’s lack of understanding was “deeply concerning”.

A UK Government spokesperson said they “do not recognise these claims”, adding the government is “focused on delivering green jobs of the future to reach net zero, with over 80,000 green jobs currently supported or in the pipeline as a result of new government policies and spending since 2020”.

They pointed to the energy department’s Green Jobs Delivery Group to support its ‘Green Jobs Plan, which will set out how the UK workforce “will develop the skills needed to deliver net zero”.

Lack of career appeal

A lack of career appeal, including limited job security, has been cited among the challenges, as well as many of the current workforce ageing out through retirement.

“Between climate change, energy transition, the encroachment of AI/Machine Learning the awful way people were treated during the downturn and a lack of future job security – experienced professionals are leaving and millennials don’t want to join the industry,” said one person in the industry.

“Therefore university departments are folding their subsurface degrees. It ensures a lack of talent pipeline for Aberdeen.”

Heriot-Watt’s Centre for Doctoral Training, entitled GeoNetZero, is unfunded and this current cohort is to be its last, the report warns.

What’s to be done?

The STF is proposing a series of measures, including company internships, additional support for geoscience education, long term recruitment, retention and training policies and supporting staff to be outreach ambassadors.

One expert said energy companies are unwilling to allocate that due fiscal uncertainty in the UK.

Constructing a positive narrative around the positive future role of the sector is also key, as students are unwilling to work for firms which are not making that positive case.

‘Simplistic narratives’ harming sector

Chair of the STF, Graham Goffey, said: “The ‘taint’ of the extractive sector which comes from simplistic environmental narratives, misdirected university campus lobbying against extractives, etc. is one of several factors deterring students from university geoscience courses.

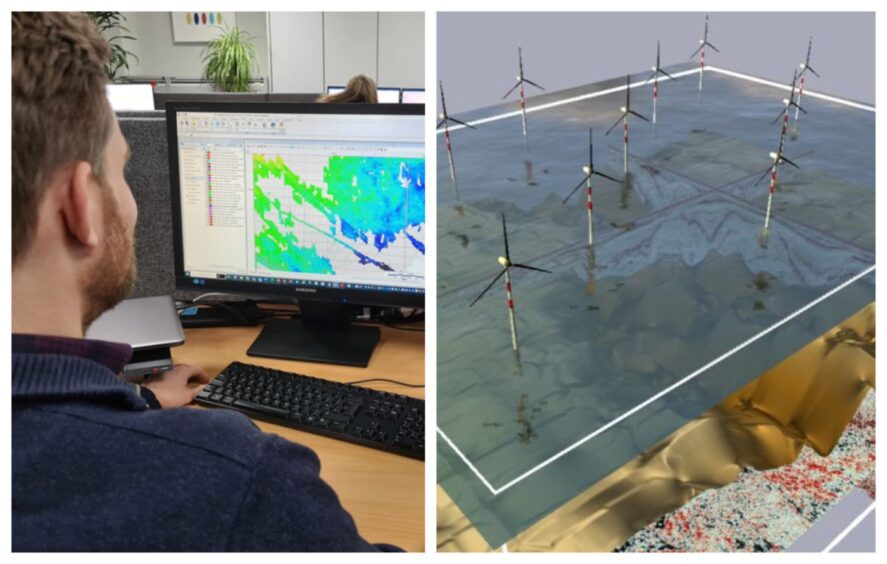

“Yet geoscience is key to our energy future and achieving net zero. It is fundamental to CCS, hydrogen and gas storage, geothermal energy, radwaste sequestration, critical minerals extraction, offshore wind development and lower emissions oil and gas extraction whilst the UK continues to consume oil and gas at twice the rate of UK production.”

Alongside the need for a more strategic approach from government, such as university funding and research, companies will need to do more to address the skills crisis through measures like internships, he said.

At school level, Scotland stopped offering geology highers in 2015, unlike England and Wales where it is still offered at A-level.

Professor Nick Schofield, from Aberdeen University’s geology and geophysics department, said the sector “relies on enthusiastic teachers to turn students to geology”, but the Scottish curriculum “is working against us.”

Beyond that, perceptions around the industry – even from academia – is causing issues.

“It must be realised that that many Universities across the UK have actively turned away from any association with the Oil and Gas sector. Many academics across the UK also have strong views against the Oil and Gas sector, which they share with students. This obviously influences undergraduates and their eventual career choice post-degree.

“We also need to look at overall where the UK energy sector is, and in particular the Oil and Gas sector. The proposed changes by Labour to the Energy Profits Levy (windfall tax) and its allowances, if it enters government, is sowing fiscal uncertainty. Due to this uncertainty, companies are understandably currently reticent to commit funds for scholarships or educational programs, in the long term at least.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by DCT Media

© Supplied by DCT Media © Supplied by Soliton Resources

© Supplied by Soliton Resources © Supplied by Aberdeen University

© Supplied by Aberdeen University