On the 3 May 2024, the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) offered 31 licences in the 3rd Tranche of the 33rd Offshore Petroleum Licensing Round.

These included 23 in the Southern North Sea (SNS) and two in the East Irish Sea (EIS) – the first to be awarded in these areas following offers in October 2023 and January 2024 for licences in the West of Shetland, Northern North Sea and Central North Sea.

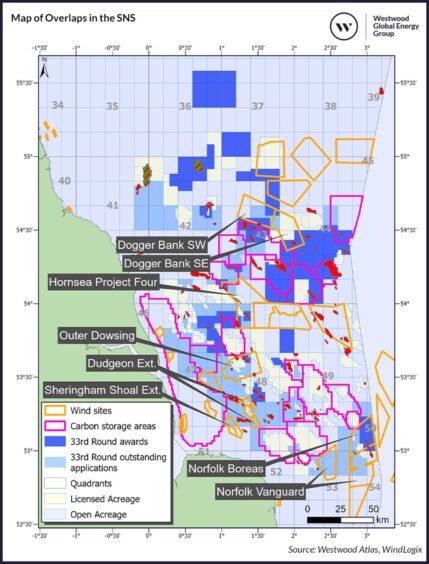

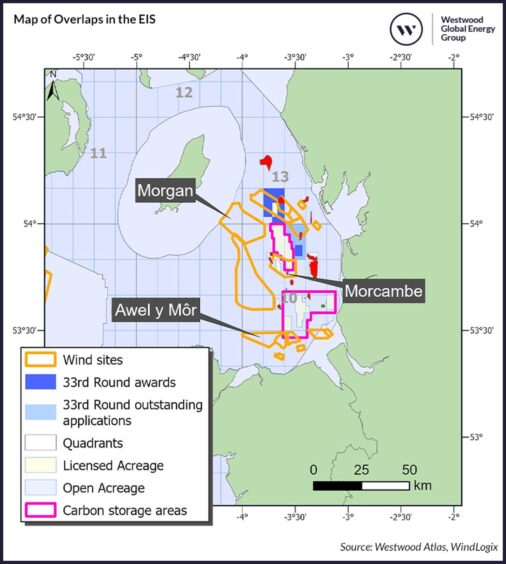

The NSTA stated that there are still remaining applications that might be offered at a later date (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Westwood understands that these licences have specific company issues that are being worked through case by case and will be awarded once issues are resolved.

Some operators believe co-location is one of the issues holding up the awards.

The SNS and EIS were already congested due to carbon storage licences lying near to or overlapping offshore wind farm sites.

These oil and gas licences add to this congestion, creating additional competition for seabed.

As a result of this, a new clause, “Relationship with Windfarms,” has been introduced which relates to O&G licence awards that either overlap with offshore wind lease sites or are within 500m of existing wind farms.

Under this clause, the O&G licensee must enter into a co-location agreement with the offshore wind lease holder before undertaking any activity.

Overlapping issues

Although the addition of this clause is a good first step, further legislation will be required to ensure that overlapping projects do not delay each other.

In total, 31 offshore wind projects are overlapping or near either carbon storage or O&G licences in the SNS and EIS.

A breakdown of the current status of offshore wind projects in the SNS shows that 11 offshore wind projects are operational, three projects have a status of EPCI[1] and eight have a status of planning[2].

The makeup of projects in the EIS are six operational wind farms and three projects that have a status of planning.

The wind farms that currently have a status of planning (as highlighted in Figure 1 and Figure 2) are the primary projects that will need to navigate any potential issues that may arise due to co-location.

Site assessments and construction activities at these wind farm areas may clash with planned activity at the awarded O&G and carbon storage sites, as drilling equipment and pipelines can potentially interfere with the placement and operation of wind turbines.

Examples of such overlaps include the Dogger Bank South wind farm being planned in the north of the INEOS-operated Greater Pegasus area, and the Outer Dowsing project which overlaps with the Perenco-operated Olympus discovery, where a firm well is planned.

In addition, Norfolk Boreas wind farm overlaps the Orcadian-operated blocks that include the 50/26b-6 Earlham discovery, which it plans to develop as a gas-to-wire project, connected to the wind farm.

Furthermore, co-location clashes may also occur when it comes to operations and maintenance activity on an operational wind farm, as marine space will be required for vessels to navigate around the infrastructure that is put in place for O&G and carbon storage projects.

Careful marine planning guidance will be required to ensure that all projects can operate without hindrance, reducing the risk of disputes that can delay project development timelines.

We have already witnessed a dispute over an overlapping zone in the SNS between the BP led Northern Endurance carbon capture, usage and storage project and Orsted’s Hornsea Project Four wind farm, which took two years for the two parties to resolve.

The developers of the two projects had entered into an Interface Agreement in 2013, to ‘regulate and co-ordinate their activities with a view to managing potential and resolving actual conflicts’, however the dispute still occurred.

It resulted in a five-month delay to the Development Consent Order (DCO) for the wind farm, further highlighting that reliance upon an agreement between parties may not go far enough.

Turning challenges into opportunities

While the spatial overlap in the SNS and EIS poses significant operational challenges, it also opens avenues for innovation and collaboration.

Electrification of platforms via wind farms on shared sites could present an alternative route to market for offshore wind projects.

Rather than constructing export cables to shore and waiting for grid upgrades to connect wind farms, the developers of the projects highlighted on the map could seek to strike a deal with the O&G licence holder, supplying power to their infrastructure via the wind farms.

This would also be advantageous for the O&G developers as power from these wind farms would help them to reduce their production costs and, most importantly, emissions.

Moreover, collaboration between project developers across the overlapping areas could take place by sharing data on the characteristics of the site and potentially utilising the same supply chain companies for similar activities.

Geological and geophysical surveys as well as environmental assessments are required for all three types of projects, creating a potential area for these synergies.

Furthermore, both wind and O&G projects utilise similar components such as foundations, topsides, and power cables, creating an additional area in which they could co-ordinate on timings for installation activity, contracting the same company to undertake installations for both type of projects across the shared site.

Enhancing efficiency and reducing conflicts

To mitigate conflicts arising from the overlapping use of marine space in the SNS and EIS, it is crucial to implement comprehensive marine spatial planning and enforce stricter regulations beyond the current clause introduced.

Promoting collaboration between offshore wind, O&G and carbon storage project developers can enhance efficiency, reduce emissions and streamline operations through shared infrastructure and data.

These solutions can ensure that the development of these essential projects proceeds smoothly and without unnecessary delays. In turn, this can help the UK to meet its energy goals while minimising conflicts and maximising the benefits of shared marine resources.

[1] A project with a status of EPCI represents projects that have taken FID. Typically, most contracts related to the manufacture and installation of associated components / stations have already been awarded at this point.

[2] A project with a status of planning represents projects that typically have developers already assigned to a specific lease site. At this stage, projects undergo Environmental Impact Assessments and follow through with national and state level permitting.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Westwood

© Supplied by Westwood © Supplied by Westwood

© Supplied by Westwood