The UK is playing catch-up with wind, both on and offshore. Even with an increased budget, the UK’s sixth renewable energy licensing round (AR6) offers onshore wind and solar little more than AR5, while supply chain constraints suggest offshore developers may remain cautious.

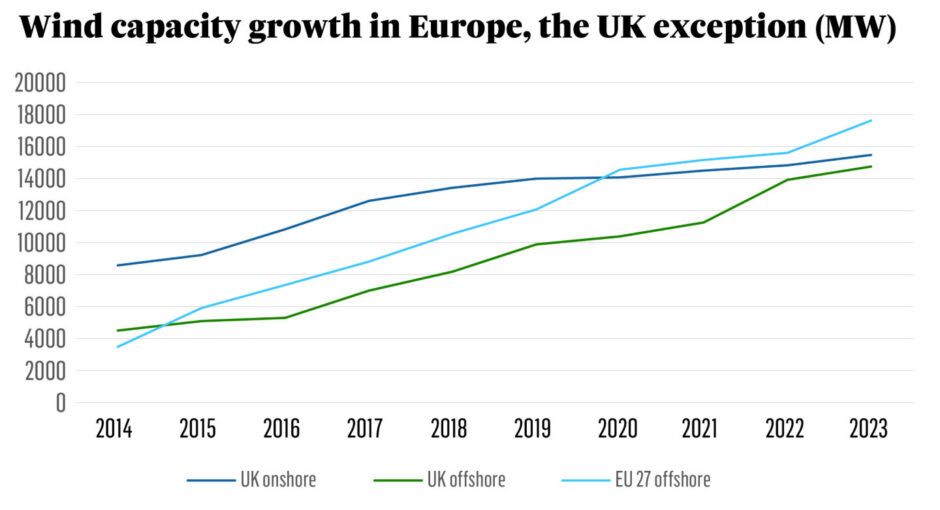

Successive Conservative governments’ heavily political approach to renewables has left the UK unique in the world as having almost as much offshore wind capacity as it does onshore – despite the latter being one of the cheapest sources of power generation, renewable or otherwise.

The neglect of onshore wind denied UK consumers cheap, clean energy and left them more exposed to natural gas prices than they might otherwise have been. Now, as gas prices and the Conservatives’ political fortunes ebb, Labour has an opportunity to revive onshore wind, and, in so doing, pick the low-hanging fruit of the energy transition that the Conservatives ignored.

It is a gift. Onshore wind and solar power are the cheapest forms of power generation. This has been fact for years; whether solar or onshore wind is king depends mainly on latitude, and the UK is northerly with plenty of wind.

In its 2023 Electricity Generation Costs report, the then Conservative government put the Levelised Cost of Energy – a means of comparing different energy sources on a common basis – for onshore wind at £38/MWh (2021 prices) for a project commissioning in 2025. Solar came in at £41/MWh and offshore wind at £44/MWh. In contrast, a combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) had an LCOE of £114/MWh.

The report didn’t bother with nuclear, probably owing to an insufficient number of beads on the abacus.

What if…

…the Conservatives had risked the ire of their rural voters and forged ahead with onshore wind?

The question is, of course, highly speculative. Politically motivated and environmentally questionable though the Tories’ approach to onshore wind was, supporting it would not have avoided the energy crisis. Wholesale electricity prices in the UK work on marginal pricing and gas-fired generation would still have been the highest-cost form of generation, setting the price for all.

More onshore wind would have meant lower emissions and less gas burn, but ultimately would have returned more cash to the electricity companies – or, if governed by contracts for difference (CfDs), to the government.

Offshore wind success

If onshore wind was the Tories’ Hyde, offshore wind was their Jekyll.

The Conservatives hobbled onshore wind in England, but they gave unprecedented support to the offshore sector, creating the largest market globally for what was an expensive technology. Providing a Hobson’s choice for wind developers created the conditions for large-scale offshore development, which in turn fostered innovation, economies of scale and reductions in cost.

Far more rapidly than expected, offshore wind developers were bidding to build new wind farms subsidy-free. In the last decade, the UK brought almost as much offshore wind capacity onstream as the EU, built by the same companies working across multiple north European markets, of which the UK was the largest.

This was an environment that saw the first commercial floating wind farm put into operation off Scotland in 2017 – a development of enormous significance, as it promises a massive increase globally in the accessible wind resource. This was a genuinely successful technology accelerator and a far-seeing policy, even if the underlying motives were as much political as they were environmental.

Downward cost trajectory arrested

Having created a world-leading market, until overtaken by China in 2021, both internal and external events conspired to throw it off course.

Multiple factors impact the cost of wind energy and a number turned against the industry. Interest rates started to rise from the end of 2021, ending a period in which inflation appeared vanquished. Materials prices – cement and steel – started to rise and jumped much higher from the end of 2022. These cost pressures affect offshore wind more than onshore wind, because project sizes tend to be larger and more capital and material intensive.

The offshore wind sector also internationalised just as domestic European markets expanded. Europe’s major wind developers are now building in the US and Asia, stretching resources and supply chains, which have become more specialised with the increase in turbine sizes.

And, in the UK, the government got greedier, introducing acreage fees and reducing the maximum strike price at which it would accept bids – helping, in the process, to push experienced developers abroad. Developers’ margins were squeezed on all sides in an environment in which auctions crystallised the effects of competition.

AR5 – not the first failure

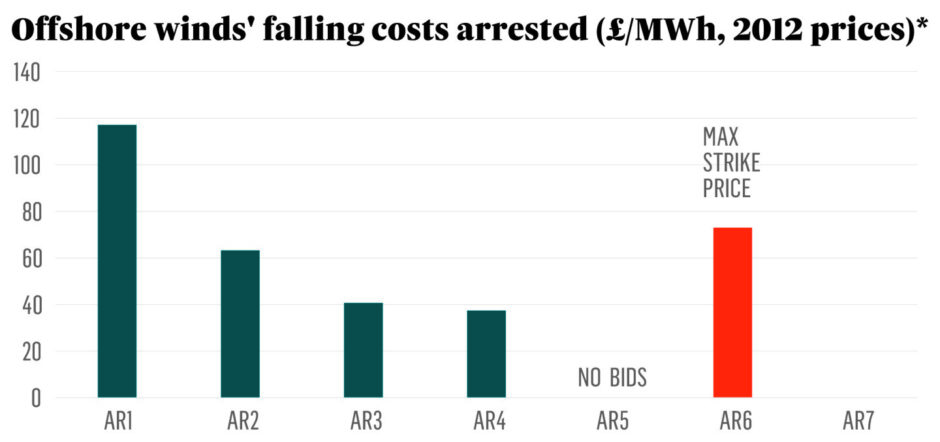

It was no surprise that a maximum bid price of £44/MWh (2012 prices) for offshore wind in AR5 attracted no interest, and, in the process, raised the heat for AR6.

Unfortunately, despite easing up to a degree on onshore wind, AR6 still reflects the Tories’ prejudices. The maximum bid level for offshore wind is a more realistic £73/MWh (2012 prices). The CfD budget is the largest ever, but even with Labour’s additional cash injection announced in August, AR6 is heavily weighted towards offshore wind (£1.1 million) versus £185 million for established technologies – i.e. onshore wind and solar – and £207 million for emerging technologies.

For onshore wind and solar, even with the increased budget, there is, in practice, little more in AR6 than in AR5, even though Labour has been quick to put onshore wind back on an equal footing with other infrastructure projects.

Maximising awarded capacity depends on bids coming in below the maximum strike price, and the shortfall to meet the 2030 target for offshore wind is more than 20 GW. This needs to be awarded in AR6 and AR7, given the long lead times required.

Auctions are curious beasts and the devil is always in the detail. Competition is good for consumers, but an overly competitive environment can result in bids that are too low. A lack of stringent non-delivery penalties increases this risk. In contrast, their presence tends to raise bid levels (some research says not) but increases the chance of delivery.

The success or otherwise of an auction does not lie in low bids, but the actual construction of projects at a price affordable to consumers and sufficiently profitable for developers. Under-delivery from earlier rounds make them just as serious a failure as the absence of offshore wind bids in AR5.

Consequently, a bout of competition fever in AR6 would not necessarily be positive.

The fact is that Labour has to play catch-up – both on and offshore. The government needs to boost the onshore sector without detracting from offshore activity. Not an easy task. Ultimately, whatever the outcome of AR6 in early September, AR7 will need to be a monster for both sectors.

Ross McCracken is a freelance energy analyst with more than 25 years experience, ranging from oil price assessment with S&P Global to coverage of the LNG market and the emergence of disruptive energy transition technologies.