My first ONS conference in Norway brought one key issue into sharp focus: energy firms are sitting on an asset that could make a huge difference to our drive towards sustainability.

But a heady mix of confusion, ignorance and conservatism make it unclear whether the industry has the inclination or ability to tap this resource.

We’re not talking about some dazzlingly innovative widget either. Every single firm already has the asset I’m talking about.

It’s the endless reams of data that energy firms generate every day, but which many find challenging to turn into usable knowledge; knowledge that could help us make rapid advances towards sustainability.

Imagine that

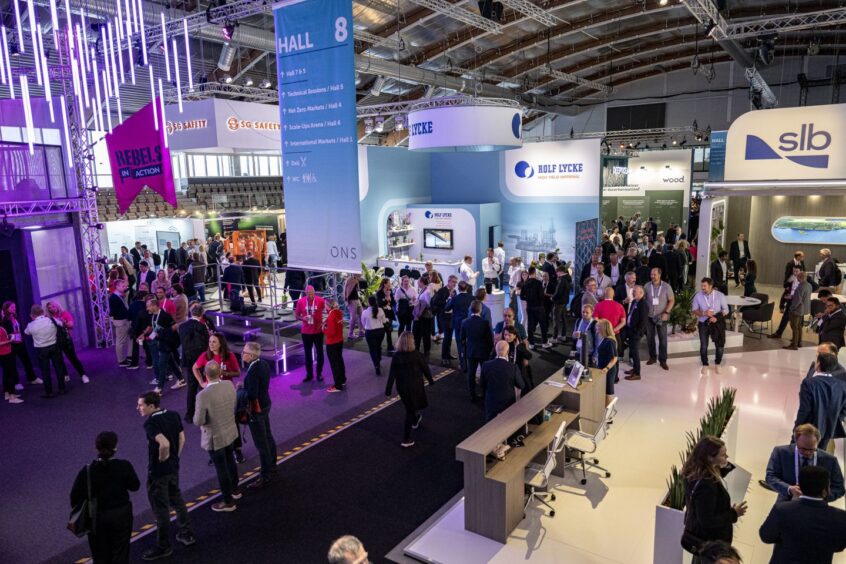

The central theme of ONS this year was ‘Imagine’, posing the question: ‘What if the worst of times brings out the best of technology to enable it all?’

And the huge conference halls were packed with technological innovation. I was briefly stalked by a robot dog.

But while there was plenty of talk, there were far fewer solutions designed to effectively free up data trapped in many organisations.

It felt like firms would have more luck finding oil buried 4,000 metres under the nearby continental shelf than extracting and using all that latent knowledge.

Conference goers I met highlighted five big questions that stand between releasing data, translating it into knowledge, and using it to drive a sustainable future.

1. Can we democratise data?

If there was an award for making data easily accessible on an ONS stand, it’d have to go to Carlo Caso, digital transformation director at THREE60 Energy.

Embedded in his company-branded t-shirt was NFC technology that brought up a host of THREE60 information if you put your phone next to it.

Caso said his t-shirt is designed to get people talking about the need to democratise data.

“In today’s energy transition industry, performance depends on how easily an enterprise accesses its own knowledge,” he said.

“Every day there’s way too much effort going into dealing with fragmented data and in different formats – no one’s consolidating it in a systematic way to liberate that knowledge and really drive core activities.

“Take an engineer who processes a large number of emails, reports, PDFs and Excel spreadsheets,” Caso explained. “There’s a huge amount of manual work to extract the information that you want.

“Instead, tech could collect, analyse and present all that data, and free up lots of time so people can concentrate on more important tasks.

“And if that’s done properly, that information is no longer the domain expertise of one engineer – it becomes knowledge that a whole organisation can benefit from.”

Caso’s lesson is simple: if an enterprise becomes more aware, it can operate more sustainably.

Avoiding the trap

The problem of fragmented data was widely recognised by people I spoke to, but for many just seemed a fact of life.

An exception was Mari Kollsgård, vice president of IK Topside, experts in working on live pressurised systems. Her view is clear.

“The green shift is being hampered by the inability of firms to turn data into knowledge,” she said. “There’s just too many bottlenecks.”

Unlike many, she’s taking steps to make sure her firm doesn’t fall into this trap, with a campaign to store every project in one ‘Lessons Learnt’ database.

“Like everyone, we have a lot of important knowledge sitting in people’s c-drives,” she said. “We are growing fast, and we need to have a management strategy to stop this becoming a problem.

“We can’t have three different ways of documenting projects; everything needs to be archived and shareable.”

The goal is faster innovation and improved outcomes for clients: a win-win.

2. Will data owners take one for the team?

It’s easy to divorce tech solutions from the humans who will make or break their implementation.

One conference attendee said they had adopted a new platform to collect, analyse and present their data.

“This was great; we got real insight quickly and easily,” he says. “But the data told a different story than we were getting from some people about performance and results.”

“Is it because the data is open to interpretation or because we’re not getting the full story? Either way, we’ve got a problem.”

Careful management got to the bottom of the issue in this case, but this begs the question: can you expect colleagues – particularly longstanding ones – to change their behaviour and adopt new processes and platforms when it could put their reputation at risk?

3. Is there too much money about?

There was an exuberance among ONS attendees. It’s understandable; these are heady times for many firms as profits rocket.

Amid the crowds, noise, giant TVs and constant supply of free ice cream (optimistic, since it rained most of the time), one conference-goer I asked about tech and change archly replied: “Look around you, how easy do you think it is to suggest that now’s the time for changing the way we do things?”

Over at the University of Stavanger’s stand, Marte Solheim, vice-rector for innovation and society, voiced a similar opinion.

“Innovation requires rethinking business models and when profitability is so high there often isn’t such willingness,” she said.

“The movement is much more likely to come from smaller players and suppliers who want to do things differently – better and faster – because they have to.”

4. Should we go easy on the big firms?

Of course, there’s more to the problem than just blaming ‘greed’ for big firms letting this opportunity go by.

You can have the best intentions in the world and still become a victim of the bureaucracy, politics and conflicting demands that dog big firms.

This is exacerbated by individuals constantly moving roles, which makes finding and implementing new systems difficult.

And this works both ways.

“The biggest challenge for a small tech company, in general, is finding the person who’s responsible for the problem you want to solve,” one tech entrepreneur in the data management space told me.

“Even when you succeed in doing that, frequent reorganisations can mean starting over with someone new,” she added. “I know someone who won a deal but it took five years for the purchase order to get signed off.”

5. Are tech firms doing their bit?

Remember ONS’ question: ‘Imagine… what if the worst of times brings out the best of technology to enable it all?’

I mentioned this to another attendee, in the context of data and knowledge. It was not well-received.

Scowling, they explained how they’d bought a tech platform that promised to gather, analyse and deliver data with ease.

“I was promised that one-size-fitted all and it did nothing of the sort,” they said. “Now I’m stuck with something I don’t use 80% of the time and needs a team to implement and maintain it. That’s before I even try to get people to use it.”

Carlo Caso, resplendent in his tech-enhanced t-shirt, said many tech firms were failing to deliver on their promises.

“If you want to succesfully turn data into usable knowledge, there’s a lot to think about and most providers haven’t done that,” he said.

Three difficult steps

“Firstly, your tool has to work, get going fast and offer value so people buy into using it,” Caso said. “It has to be easy to use too, otherwise people will lost interest.”

“The tech then has to retain this expertise indefinitely and make it easy for everyone to access. Only then does it become a knowledge base with a purpose.”

“Finally – and this is a killer – it actually has to solve your specific problem and fit with your operational habits. So many solutions are one-size-fits all and they just can’t deliver that.”

That’s a lot to ask of technology, and you have to wonder whether the latent potential of turning data into knowledge will truly be exploited to drive the energy transition.

6. Will a new generation of workers turn the tide?

Millennials and Gen Z are forever being lambasted for their desire for quick fixes and easy solutions, all to help drive their quest for purpose.

But when it comes to the energy industry this could force change.

Manpower’s green business development director, Steinar Instefjord, said digital natives expect systems that chime with their experience of using the likes of Spotify or Uber.

They have a low tolerance for scrabbling around emails and PDFs for information.

“There are plenty of employers who don’t think it’s reasonable to give recruits the same kind of digital experience that they expect from the platforms they have on their phones,” Instefjord said.

“But tech – and the workplace experience that offers – is absolutely part of the employer proposition.”

“Of course, company heritage, opportunity and money play their part, but if you want the best people, you can’t just rely on that anymore.”

Rebel yell

There’s clearly a lot to do if we’re going to mine this deeply buried but rich sustainability resource. Is it too much?

I’d argue ‘no’. For one, the spotlight is definitely on data. The awareness at ONS proved that.

Moreover, the tech will improve (and fast), and there are people working hard to deliver solutions that will be truly fit for purpose – and that can be delivered before contacts move jobs or lose interest.

Perhaps then, we should ignore ONS’ request to ‘Imagine’ and be more like Aker BP, the self-proclaimed ‘Rebels’ of the conference.

They emblazoned one wall of ONS’ monstrous halls with a different message.

‘Don’t Imagine: Act’.

Michael Millar is co-founder and partner at SmplCo, helping the energy industry to innovate fast by creating their own digital platforms, products and services.

© Supplied by ONS

© Supplied by ONS © Supplied by ONS

© Supplied by ONS