The mining industry is currently one of the most significant contributors to planet-warming emissions — but it’s on track to become one of the most important sectors for a net-zero future.

Annual demand for energy-transition metals will grow fivefold by mid-century from 2023 levels under more aggressive action, according to BloombergNEF.

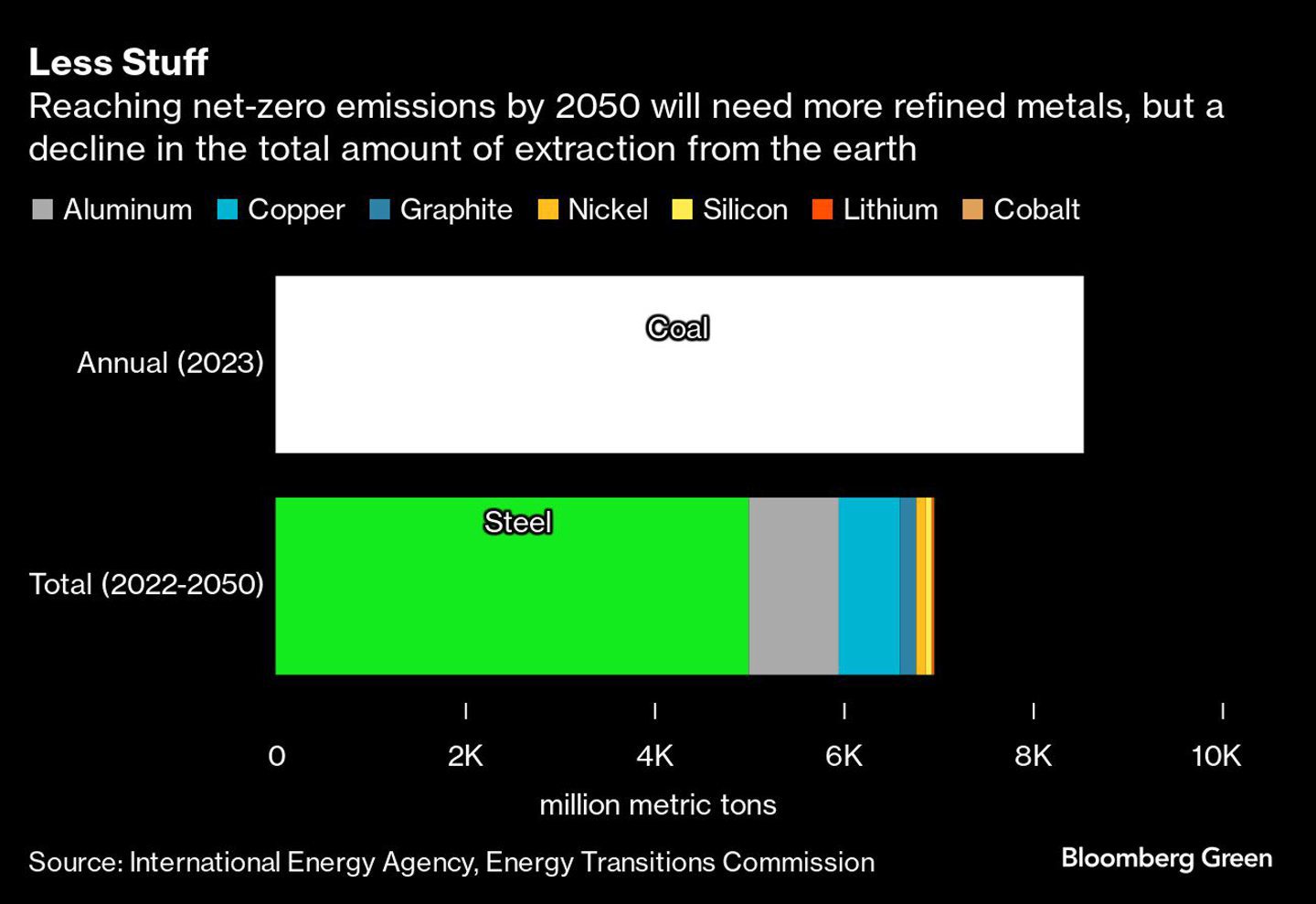

Yet that doesn’t mean we need to extract more stuff — in fact, we need less. While EVs and clean energy infrastructure will mainly consume electricity and require lots of metal, the total amount of materials the world mines will fall. Specifically, we’ll need almost no coal — which still contributes significant revenues to mining companies.

In fact, all the refined metals needed to reach net zero by 2050 will add up to less than the amount of coal mined in 2023 alone, according to think tank Energy Transitions Commission.

It’s worth noting these figures do not include the full weight of extracted ore, which often contains a small concentration of metal. The figures also don’t show the weight of extracted oil and gas. This is important because, all combined, fossil fuel taken out of the ground today still outweighs mined ores.

The metals that will be extracted into the future can also be recycled — unlike fossil fuels — meaning the world isn’t doomed to finding endless new sources. “It’s a shift from a single-use, extractive and linear energy system that has shaped our past energy system where fossil fuels once burned become greenhouse gas,” said Daan Walter of RMI, a clean-energy think tank, “to a multi-use, renewable, and recycled energy system of the future, where the world traps solar and wind power with metals that are used again and again.”

While there’s plenty of room to improve recycling rates of all the stuff that can be recycled from paper to plastic, more than half the energy-transition metals — steel, aluminum, copper and cobalt — are typically recycled after they reach the end of life, according to the International Resource Panel. And RMI’s analysis shows that recycling capabilities are rising rapidly.

Beyond recycling, other technological advances have led to huge declines in the use of metals already, according to a recent analysis from Walter and his RMI colleagues. Those include improving the storage capabilities of battery material and substituting metals with other cheaper or more abundant materials. Without those factors, the world would be consuming 138% more cobalt today, 127% more nickel and 58% more lithium — all metals that are used mainly in lithium-ion batteries.

When you factor in the emissions reductions that come from EVs and clean energy, mining seems to be on its way to becoming a more positive — rather than negative — force on the planet’s climate. But there are other important elements that must be addressed.

First, mining itself is resource intensive and greater strides must be made to improve its efficiency and reliance on zero emissions energy sources. Digging for metals also produces a lot of unusable earth and therefore recycling will become more important over time to reduce the need for continuous exploration. Finally, the sector needs to reckon with concerns of alleged child labor and trampling of Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Yet mining will be crucial to reaching net zero. After all, Walter notes that not reducing emissions from burning fossil fuels will set the planet on course for even greater destruction from climate change.

“We need to be aware of the trade-offs in our system,” he said.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg