“We will ensure the long-term security of the sector, extend the lifetime of existing plants, and we will get Hinkley Point C over the line.”

That was Labour’s manifesto commitment to nuclear power, and the government has already put money on the line. In late August, it announced additional funding of up to £5.5 billion for the proposed Sizewell C plant, which would be only the UK’s second nuclear construction project since the completion of Sizewell B in 1995, if built.

However, for the UK consumer, nuclear new building means expensive electricity and offers little in terms of addressing climate change.

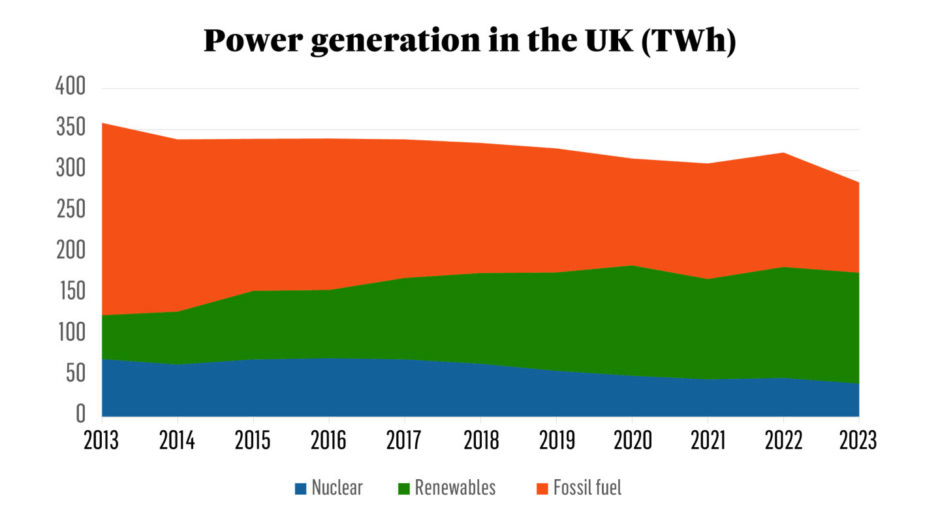

Capacity decline

The UK’s operable nuclear capacity declined from 12.2 GW in 1996 to 5.8 GW in 2023. Only nine reactors are still generating power and two are under construction. Eight of the operable reactors came online between 1983 and 1989, making the youngest 45 years old.

Last year, the Hartlepool and Heysham 1 plants gained modest life extensions to 2026, and operator EdF hopes to extend the lives of its other Advanced Gas Cooled (AGRs) reactors to 2028.

However, there is little likelihood that the eight remaining AGRs can continue in service beyond these dates. They were initially designed to last about 30 years, with the decision to decommission based on the deterioration of irreplaceable components such as the graphite core and boilers.

Three AGRs – two built in 1976 and one in 1983 – are already defueling, a preliminary step to decommissioning. As a result, by 2030 at the latest, all of the UK’s AGRs will be out of service.

Decommissioning costs the consumer money, and the Nuclear Liabilities Fund has not kept up with the cost of decommissioning. In its third report of 2022-23, the House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts noted that the government had already been forced to provide additional funding of £10.7 billion and that there remained “a strong likelihood that more taxpayers’ money will be required”.

In addition, despite the first nuclear reactors coming into service in the 1950s, there is still no clear plan for the permanent storage of the most hazardous forms of radioactive waste.

With the AGRs gone, the 1.2 GW Sizewell B will be the only nuclear plant left operating in the UK. It is a Pressurised Water Reactor licensed to operate until 2035, but with a likely life-time extension to 2055.

Hinkley Point C

Two reactors are under construction at Hinkley Point with combined capacity of 3.2 GW. The cost of Hinkley Point C has climbed ever higher since its start in 2018, and the likely commissioning date has receded. In January, EdF said the plant would not be ready until 2029-2031 and that the cost had risen again to a massive £31-35 billion in 2015 values. According to the Bank of England, a pound in 2015 is the equivalent of £1.34 today.

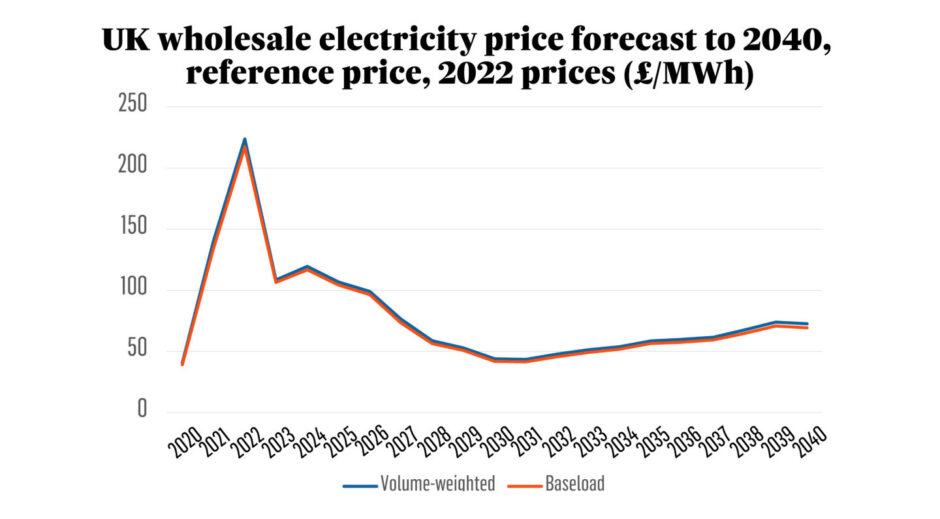

Electricity generated by Hinkley Point C will be paid for via a contract for difference (CfD) with a strike price of £92.50/MWh based on 2012 prices. The strike price rises with inflation and the state pays the generator the difference between it and the wholesale price of electricity, if the latter is lower.

The government’s most recent energy and emissions projections, published in November 2023, forecast the volume-weighted wholesale electricity price in 2030 at between £36.6/MWh, in a low fuel price scenario, and £58.5/MWh in a high fuel price scenario.

The UK’s latest licensing round for renewable energy, the results of which were announced in September, returned CfD prices for solar projects of £50.07/MWh, onshore wind at £50.90/MWh and offshore wind at £58.87/MWh (2012 prices).

At over £100/MWh in today’s money, even without a further five years of inflation, Hinkley Point C is a chronic deal for the UK electricity consumers.

However, that doesn’t mean it’s a great deal for EdF. Each month of delay increases the interest paid on money borrowed, and the total construction cost is EdF’s problem. As the costs blow out, the company’s expected rate of return must fall because the revenues are fixed by the CfD strike price.

EdF, which is state-owned, has low borrowing costs and can take a long-term view of returns over the full, potentially 60-year, life of the reactor. Nonetheless, Hinkley Point C is still something of a loss leader – the first European Pressurised Reactor in the UK and one of the first in the world – which the company hopes will lead to further deals, lower construction costs and quicker construction times.

In terms of the energy transition, however, the timing is poor. The UK will have a maximum of 4.4 GW of nuclear power in 2030 – less than today. If Sizewell C sees a final investment decision next year, it will probably not be operational until 2035. And there is no guarantee it will be any cheaper than Hinkley Point C.

The bulk of the targeted 24 GW of nuclear capacity by 2050 will not arrive until the 2040s: too late to have much impact on climate change.

UK consumers will bear the cost

EdF wants a new funding model for both the construction of Sizewell C and the lifetime extension of Sizewell B, indicating that even the large CfD strike price for Hinkley Point C is not enough to build new nuclear in the UK.

This will almost certainly mean UK consumers bearing more of the risk. The adoption of the proposed Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model would see consumers paying for nuclear plants years before they actually generate electricity.

EdF is right when it says the way to reduce costs is “build and repeat”. But this is hard to do in a sector with such high safety risks; reactor designs and safety regimes undergo constant change.

In fact, the only time nuclear newbuild costs have fallen in the OECD was in the 1990s when South Korea and Japan built a series of the same model. However, even that fall in costs would have to be re-evaluated today in the light of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, owing to the resultant (huge) amount of lost operating time, increased spending on safety and early closure of multiple reactors.

Nuclear power does, of course, have attractions. It provides consistent power but so, too, do renewables plus storage – and at significantly less cost, according to Lazard Bank’s latest Levelised Cost of Electricity analysis published in June.

Nuclear provides jobs. Last year, the number of people employed in the UK’s civil nuclear sector rose by 20% to 77,143, the highest level in 20 years, according to the Nuclear Industry Association. The Office for National Statistics puts the number of full-time equivalent jobs in the nuclear sector much lower at 23,100 in 2022, lower than renewables and less than 10% of total low-carbon and renewable energy employment.

And nuclear science is an important area in which the UK should not fall behind.

But is civil nuclear power affordable? The government has already highlighted a “£22 billion black hole” in the public finances left by the previous government.

Embarking on the ‘build and repeat’ programme of new reactors necessary to meet the target of 24 GW by 2050 would be a massive financial commitment, even if cost reductions were achievable. And, under the RAB model, it would hit consumers’ bills early and deliver electricity somewhere around twice the price of renewables. Try selling that to the UK consumer.

Ross McCracken is a freelance energy analyst with more than 25 years experience, ranging from oil price assessment with S&P Global to coverage of the LNG market and the emergence of disruptive energy transition technologies.