The Xlinks Morocco-UK Power Project, which “exists to capture the power of nature to generate a near constant, affordable energy supply and connect it to the point of consumption in real time”, is more than just an already-sizeable project. It is the first step toward realising Xlinks’ shared concept of the ‘Global Grid’ – a series of interconnected, mutually supportive supply balancing systems laced across the globe.

In our exclusive interview, Energy Voice spoke to Xlinks chief executive James Humfrey to discuss the scope and hurdles facing the nascent 3.6 GW renewables megaproject.

Humfrey has over 25 years’ experience in the energy industry, most recently as EVP for growth and industry in ADNOC in Abu Dhabi. He also led ADNOC’s New Energies Division, developing the region’s first world-scale Blue Ammonia plant and CCS pilot and delivered the acquisition of a stake in Masdar and the formation of Masdar Green Hydrogen.

Energy Voice: Where is the project right now in terms of recent milestones? What do you have in the pipeline?

Energy Voice: Where is the project right now in terms of recent milestones? What do you have in the pipeline?

James Humfrey: Recent milestones would be on the financing side where we closed Series B and further enhanced our strategic blue-chip investors, with GE Vernova joining as well as Africa Finance Corporation (AFC). That complemented TotalEnergies, TAQA and Octopus Energy.

We also announced the appointment of our advisors on the debt side, JP Morgan and Societe Generale, and they’ve been helping us lead in – in terms of preparing the financing side. On the permitting side, we’ve undergone public consultation as part of the DCO process as a nationally significant infrastructure project. That happened over the summer and that’s a matter of record, including town halls in Devon, while our wind management campaign continues on site.

I think that’s now one of the longest-running measurement campaigns and we continue to get the data – that’s over two years’ worth.

On the route itself, we’ve got three survey vessels out at the moment, which are doing some of the environmental studies as part of the installation permit work that will come next year. So lots of activity on the marine side, and then in terms of the technical work we’ve got a huge amount of procurement – we’ve probably done about 95% of all of the procurement tenders that are out in the market, and we’re getting the first bids back. That will complete next year.

So there’s a lot of work there on the technical commercial side with our supply chain partners and lots happening across many fronts.

Where does the project stand in terms of securing finance?

We’ve been fortunate to have these excellent equity investors. They are strategic blue chips who share our overall vision of the Global Grid, the importance of long-distance transmission in supporting the decarbonisation of the grid and mitigating some of the intermittency challenges that renewable energy brings – but while benefiting from its low cost and proven technologies.

When it comes to the construction phase, we will be project financing as it’s a substantial size project. Construction sort of £22 to £24 billion and that will be project financed and they’ve been helping as we prepare for the market with that engagement with commercial banks with Ecas in order to do market assessments and soundings. So that can be ready towards the end of next year.

So how close would you say it is to being a done deal?

A done deal is when we reach financial close and we’re working hard towards that and making lots of good progress – but that will be in 2026. So we’ll continue to work towards that.

There are some constant themes when you’re developing large mega projects. I think one of the important things is that you need to maintain the momentum across a wide range of fronts. You can’t let some pieces get ahead of others, and that’s similar to other large-scale mega projects I’ve worked on before.

In that sense, the rhythms and challenges feel familiar. You have to constantly be looking to mitigate your risks. You take your opportunities and you progress all the different workstreams in lockstep.

Beyond the financial challenges, could you go into more detail on the physical challenges involved in constructing such a long-chain project? From constructing the generation facilities in Morocco through to other potential hurdles on the road to making this project a reality, where do you anticipate the greatest challenges?

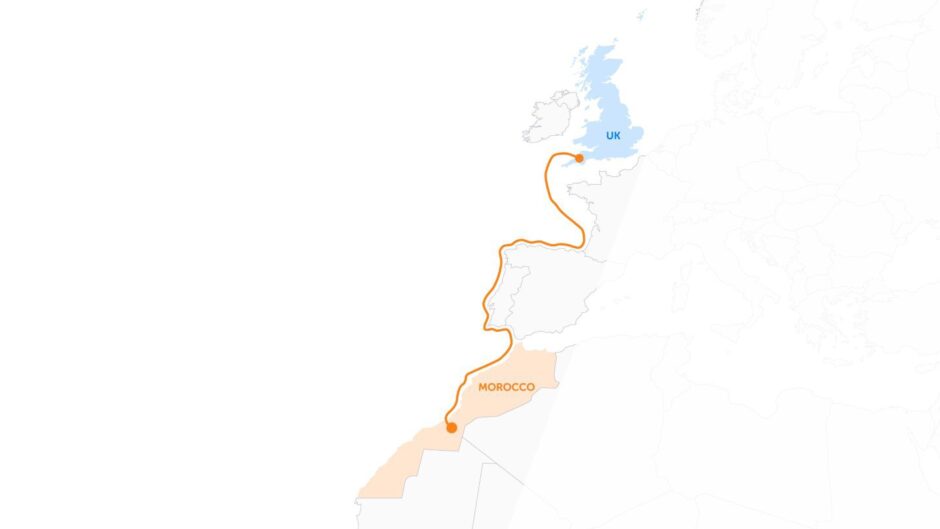

The greatest challenge on projects like this is bringing all the pieces together. Let me take you through the route and you’ll get a sense of the scale to better understand what we’re undertaking.

Fundamentally, you start with the site itself in Morocco. It’s a very large-scale site, it’s remote and we’ll need to build camps and utilities so that we can develop the site.

You’ve got the 140 km connection of the route to the coast, so all of those connections have to be built. You then have the subsea cable, which will arrive in North Devon. But, of course, that involves the installation of the cable and a significant series of marine campaigns – all of that has to be prepared.

And then you move on to North Devon where you have the work to the converter next to the substation, and then that enters the grid. So you’ve got work taking place in two different locations, two countries – you’ve got the marine work and all of that technical work has to be developed in terms of the design, engineering and then supply chain and procurement.

All of those are divided into packages and you’ve got to have the right suppliers ready to mobilise and then execute, once you’re into the construction phase.

Do you already have a site confirmed for the construction of the renewable generation combination of solar, wind and battery?

We do, in agreement with the Moroccan government, and that’s where we’ve been doing our measurement campaigns the last few years. That’s all been agreed, and all of our technical planning is based on that.

To recap, we have about 11.5 GW of wind and solar – that’s about 7 GW of solar, 4.5 GW of wind and then 5 GW of battery. Morocco has terrific renewable energy resources and the reason for this is that you have not only high radiation levels somewhere that far south, and on the edges of the Sahara – at least two times more than the UK – but you also have a different type of wind.

You have these trade or convection winds that come up in the evening as the land mass cools down, and those are very consistent winds. So you have this combination of strong solar during the day and winds that pick up late afternoon into evening, and this allows us to offer a really attractive energy profile to the UK – we’ve optimised it around when the UK grid needs it most: roughly between 4pm and 7pm.

You also have the ability to be very flexible in the supply. And if you have a period of low wind, sometimes called a ‘dunkelflaute’, our project profile provides consistent energy. In fact, we’ve done the analysis of the wind patterns in Morocco versus the wind patterns in the North Sea, and they’re actually slightly negatively correlated.

That’s to say that, if you have a dunkelflaute, there is no impact on the wind – the consistent winds that you’re getting in Morocco. Whereas if you have periods of low wind in the North Sea, you know that’s also going to impact other neighbours and their own offshore wind and wind generation into their own grids and the interconnector market.

So having this lack of correlation is really important, because we can offer a diversified supply with a really unique profile for the UK grid – and it all comes down to, effectively, the differences in the solar and wind patterns.

If you think about it, that’s really the key element of the Global Grid vision. The idea of moving electrons in time and space is so that you can take advantage of different seasonal patterns, different sun and wind patterns, so as to make the grids more resilient. And that’s why we believe in it as an overall concept.

Obviously, the first thing we’re focused on is the Morocco-UK project to demonstrate that it can be done at scale. But I think as we do that the idea will further gain traction and that, just as you’ve seen internet cables crossing the world, you’ll also see the Global Grid expanding in a similar way.

Is the Global Grid concept an initiative you share with other companies or is it something that Xlinks is leading on?

We like to think we’re leading in terms of the advanced nature of this project. And I hope that on the back of experience we’ve developed on this project, and some early-stage future projects, that might make us a good choice to develop other projects going forward.

But I also think it’s a big world. And yes, there will be other players – but you know, that’s good. That’s good for the industry. That’s good for the Global Grid and there’s a huge amount of work to be done around the world, and that needs many players. So we’re very supportive. We want to be at the forefront of the industry, but of course you want many more people involved.

On the subject of the physical challenges around interconnections and the practical challenges of actually balancing the UK grid, are you able to provide a bit more clarity on where the project is at in terms of offtake agreements?

We’re in discussions with the UK government for a contract for difference (CfD), which is obviously a familiar mechanism for many industries in other contexts. We’re making good progress with the government through that, and that’s a multi-stage process.

So that’s in terms of the offtake and that’s important because a UK government CfD does very much support the project finance I mentioned earlier. And then in terms of the grid, yes, we have our National Grid connections, which are all signed.

I think one of the advantages of subsea transmission cables is you’ve actually got some flexibility where you come on shore. And one of the advantages in discussion with National Grid of coming in at Alverdiscott (North Devon) is that you don’t need grid upgrades there. The Southwest is a part of the country with high power demand, and therefore bringing supply into that corner of Great Britain is actually very advantageous from a grid perspective – it could save £5 billion in dispatchability costs.

That’s another advantage of the Global Grid – it also helps to mitigate some of the grid congestion issues that many countries are working through.

In the sense that if you if we were able to establish a global grid that would help balance grids at a national level?

Indeed, that’s one dimension – grid resiliency ultimately grows with scale and diversity of inputs and outputs but also, in particular, it helps reduce the grid investment that’s required – and so that’s more cost efficient.

You know, if you’ve got everyone trying to come in through the same part of the grid you’ll greatly increase the cost of upgrades etc. and congestion, and so that’s really the advantage of coming in via the Southwest – for the grid connection.

How can Xlinks maximise the potential of the decline in the cost of renewable power?

In essence, the whole concept of Xlinks and the Morocco-UK Power project is to benefit from the reductions in the cost of renewable energy, and that is what allows us – in a cost-effective and affordable way – to provide that electricity to the UK, which is 4,000 km away in terms of our route.

A combination of cable technology evolving with the reduction in the last decade of low-cost renewables, it suddenly enables this to be possible at scale.

That’s what I think will be transformative and will help create the Global Grid. Interconnectors have been around for a good amount of time in the UK – we have been very pioneering in that. But they have typically been on shorter distances and they’ve been interconnectors rather than generation and transmission to a location, which is what the Xlinks concept is. That’s what makes it different to what’s been done in the past.

And finally, what would you say to people who, albeit may not be that familiar with the project, say it will never happen because of the distances involved and the practicalities – how would you counter that?

That’s a reasonable question and I’d say a few things in response. First of all, we have a strong A-Team that’s done these types of projects before – or components of these types of projects. For example, Nigel Williams was the project director for North Sea Link and that team has a lot of experience from building out interconnectors in the past.

So that’s the first thing: we have a great team who were some of the pioneering forces in the 2010s through some of the renewable power build out in Morocco, including our vice chairman Paddy Padmanathan, who was CEO of ACWA Power and pioneers a huge amount of solar and wind. He’s actually sometimes called the ‘Usain Bolt of solar’ because he really drove down the cost.

Secondly, when you look at it from a technical perspective, actually there’s nothing in there that hasn’t been done before. Everyone’s very familiar with battery, wind and solar and Morocco is a well-established market for renewables. The transmission cables themselves, they’re not interconnectors – it’s the same technology that has been used in interconnectors and therefore lots of experience there.

We don’t go to unusual depths. In fact, that’s why we sort of hug the coast. So we’ve taken away the technical risk there – in fact I think the next frontier for long-distance transmission will be deeper waters. But we’re not doing that in this project, so it remains well within the envelope of tried and tested.

I think the difference we’ve got is scale, but actually if you break it down into the component parts, things have been done. We’ve got excellent investors. As I mentioned, we’ve been really pleased with the market sounding from the debt side. So from a financing perspective this is doable as well.

And then, finally, we’ve had great support from the UK and Moroccan governments. I think for the Moroccan government it very much aligns with their green industrialisation strategy. This project will generate a lot of high-quality jobs in Morocco and the UK and many thousands more, through indirect jobs, because we have a lot of supply chain and local content plans as part of the supply chain. So all of this drives good support and benefit for the countries and fits the long-term strategies.

So if you put all of those pieces together I think that’s what makes this project, and all of our investors have done detailed due diligence – they’ve really kicked the tyres and are pleased to support us.

So I guess that means you’re fairly confident that the project will make its mooted launch date of the “early 2030s” for Moroccan-generated renewable energy to flow to the UK?

Yes, the project will begin supplying Great Britain with renewable power from the early 2030s.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Xlinks

© Supplied by Xlinks