A decarbonised power system is certainly possible and certainly desirable, but it will be no easy task for a large economy historically dependent on fossil fuels. It will require radical changes in the way the UK generates power, the electrical system’s ability to deliver that power, and the way the entire system is operated. All this must happen simultaneously in a coordinated fashion.

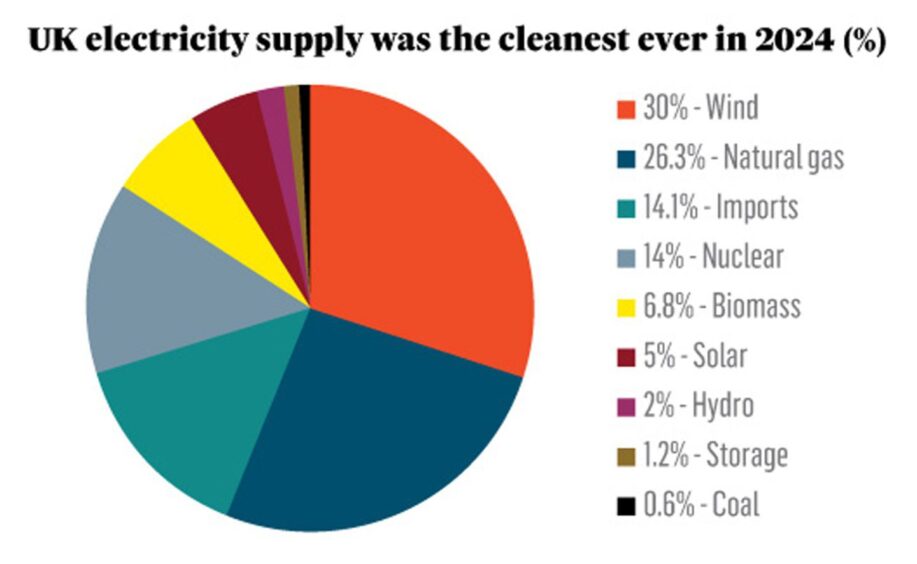

UK electricity demand in 2024 stood at 314 TWh, significantly higher than in 2023 but in line with the average of the last five years. Of this, 14.1%, or about 44 TWh, was imported. Last year, only about 30% – 91 TWh – of power generation came from fossil fuels, primarily natural gas, the UK’s last coal plant having closed in September 2024.

Replacing this capacity with low-carbon alternatives in the short time available is a tall order.

Non-runners in the generation expansion game

The low-carbon elements of the UK’s power system contain some significant non-runners, when it comes to generating bulk power.

Nuclear will be unable to generate more power by 2030. More likely it will generate less. The decision to extend the life of four of the UK’s ageing reactors will still see Hartlepool and Heysham 1 close in 2027, while Torness and Heysham 2 operate until 2030.

The under-construction Hinkley Point C plant is expected to come online around 2030, which would leave it and the Sizewell B facility as the UK’s only operating nuclear power plants. When Hinkley Point C starts operating, the UK’s operable nuclear capacity will still be 1.5 GW less than today.

Biomass, which provides important dispatchable generation, provided 13% of the UK’s power in 2024, but it will not expand because it is not low carbon over short time spans. Wherever one stands on the debate over biomass for power generation, sufficient controversy surrounds wood burning to leave it in the illogical position that it should not contract, because renewable energy targets will be missed, but it must not expand, for the same reason.

Carbon capture and storage might offer an expensive way of digging biomass out of this Helleresque impasse, but it is not a formula for rapid growth.

The UK does not have much hydropower – this is a fact of nature. It does have substantial tidal power potential, enough to more than outstrip nuclear’s declining contribution to the UK’s energy mix. However, for reasons foul and fair, the impetus to exploit this clean, predictable resource has floundered for decades and has no immediate prospect of development beyond a nominal amount of tidal stream turbines.

Depending on the wind and the sun

This means wind and solar have to make up the shortfall in generation implied by the phasing out of gas-fired power. The two stalwarts of the energy transition will also have to meet a likely increase in demand as a result of more widespread electrification. This gap, in bulk terms – given the drop in nuclear generation and expected demand growth – is in excess of 100 TWh.

The omens are not good.

Solar power has been growing incrementally in the UK rather than exponentially. However, comparisons with other north European countries suggest that if the policy settings were more attractive, much faster growth could be achieved.

The Netherlands for example, which is much smaller than the UK, had almost 24 GW of solar installed at the end of 2023 – significantly more than the UK’s meagre 15.6 GW. Between 2019 and 2023, Poland managed to install 14.3 GW of solar to make a total of 15.8 GW, overtaking the UK’s 15.6 GW. For an economy of its size and income levels, solar power in the UK could be deployed at a much faster rate.

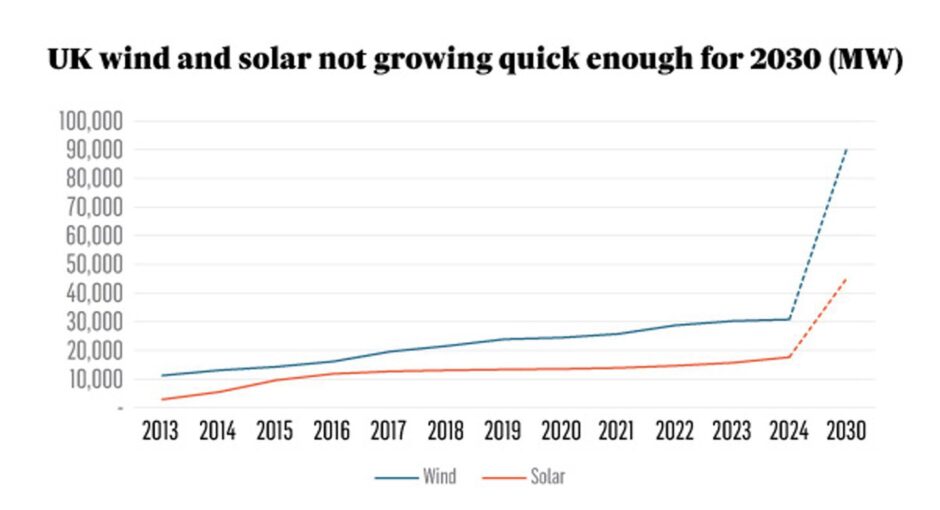

As such, the government can achieve a large part of its targeted tripling of solar capacity by 2030 to 45-47 GW. But to ‘only’ double capacity would take a near tripling of current deployment rates and then provide only about 15 TWh of power. Consultants Cornwall Energy take the view that the target shortfall by 2030 will be 16 GW for a total of 29 GW installed.

Achieving a clean power system in the UK context therefore depends heavily on wind generation, which needs to roughly double in the next six years based on bulk power generation calculus. In reality, capacity needs to treble because of the variability of both electricity supply and demand.

Bungled auctions

The government’s aim is to double onshore wind capacity and quadruple offshore wind by 2030, which would mean an increase in total wind capacity from around 30 GW to 90 GW.

On the current trajectory, this will not be achieved. The blame can be laid squarely on the Conservatives’ antipathy towards onshore wind, coupled with the mismanagement of auctioning rounds. In the period 2019-2023, the UK added just over 6 GW of new wind capacity. Last year, it was some 600 MW.

Even if Labour has moved quickly to lift the effective moratorium on onshore wind in England and Wales, 60 GW of new on and offshore wind is needed in the next six years – a huge step up in construction.

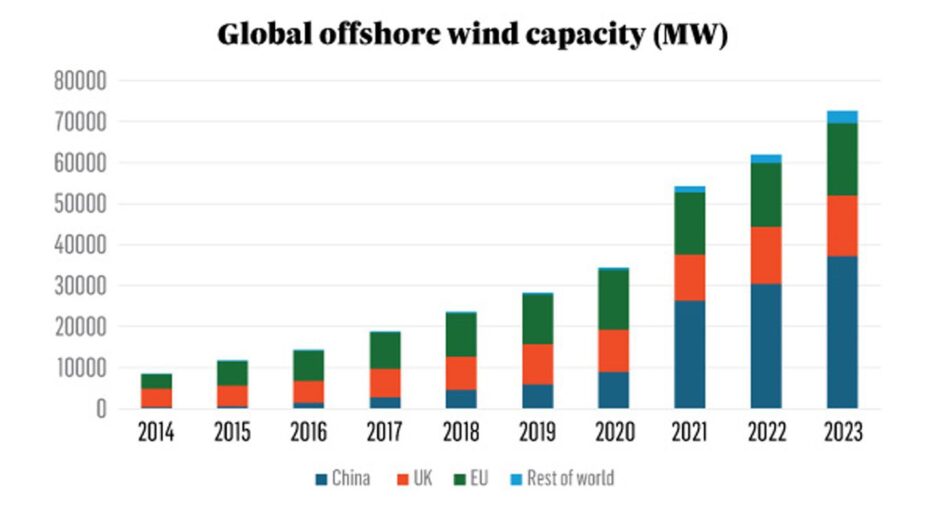

The bungled AR5 auction in 2023 returned no new offshore wind capacity. AR6 returned 3.3 GW of new offshore wind and just under 1 GW onshore. As it takes five to six years to build an offshore wind farm, the UK is already running out of time to deliver the capacity required. This year’s AR7 needs a record-setting result, followed by speedy deployment.

But even if AR7 delivers, there may not be sufficient construction capacity within the supply chain to build the required amount of new wind generation offshore. The UK wants 45 GW of new offshore wind capacity in six years – the entire world managed to build 49 GW in the five years from 2019-2023 and, of this, 32.7 GW was built in China.

So how will the headlines run in 2030? ‘UK misses clean power targets’ or ‘UK builds record new renewable energy capacity’? Both are likely to be true…

In part two of our series, Going to the wire: the biggest upgrade in history, Energy Voice will examine the second critical element of the 2030 target: power transmission. Here, the timeline looks even more ambitious.

Ross McCracken is a freelance energy analyst with more than 25 years experience, ranging from oil price assessment with S&P Global to coverage of the LNG market and the emergence of disruptive energy transition technologies.