Money and lots of it . . . public and private . . . is needed to initiate a credible wave and tidal energy power generation sector in the UK, which a new report claims could be worth up to £76billion to the economy.

However, the idea that the oil and gas supply chain can kick-start the market “is not easily realised” because it is “too expensive”, according to a new report by the Glasgow-based ORE Catapult initiative.

It claims that this is because the oil and gas supply chain designs and makes equipment to “operate at extreme depths, in benign tidal flows, and low oxygenated waters”.

The report gives zero credit for the fact that a lot of the North Sea does not require “extreme depths” technologies or that the waters West of Shetland are in fact highly oxygenated.

ORE Catapult is, however, correct in stating that “developing a supply chain that understands the market and is then prepared to invest and support the non-core enabling technologies is essential for the success of the overall industry”.

But a putative supply chain can only develop when there are sufficient projects to bid into and therefore to enable investment in the necessary wherewithal to enable a credible capability to emerge.

Even in the very highly developed oil and gas industry supply chain, many technological advances do not make headway unless there is money on the table and a significant proportion of high-end support vessels and drilling tonnage is only invested in against a long-term contract.

The report admits that wave and tidal energy technologies are still in the development stage with low levels of deployment to date and that the “levelised costs” are relatively high compared to other renewable energy sources. The sector is floundering.

It says: “Effectively harnessing this large, indigenous resource will unlock major benefits to the UK, including greater security of energy supply with a lower carbon intensity and material economic growth.

“Government (including regional governments) are therefore keen to promote advances in these technologies and have put policies in place to create a more attractive market for this embryonic industry.

“This includes the Contract-for-Difference mechanism as part of the recent Electricity Market Reform, a market-based solution to channel grant funding to the relevant technologies and technology components.”

ORE Catapult seems content with the level of government support for marine energy but states that there is a strong need for private sector investment over the next few years, alongside the available public sector support, as these technologies move towards commercialisation.

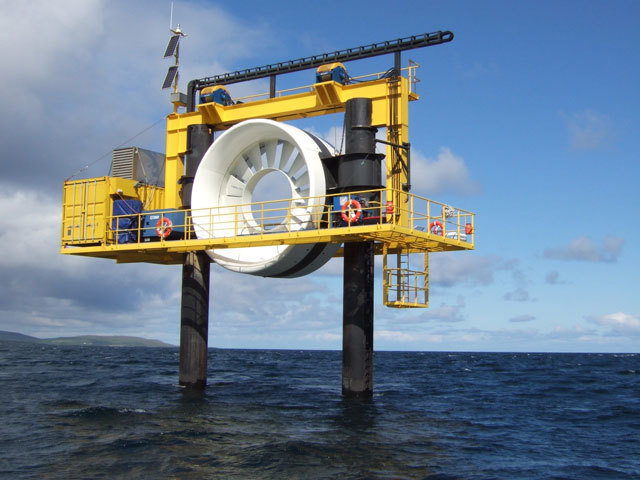

It says too that the gap between the technology readiness for wave and tidal has widened in the past few years: tidal energy devices have been through the proving stage and are now coming to the point of contracting the first demonstration arrays, while wave technologies are still at the device proving stage.

As a result, different interventions and support are required for each.

On tidal, Ore Catapult warns: “Looking at a typical project, we estimate that between 30% and 50% of the required funding has yet to be secured in some cases.

“The need for private sector funding in these initial tidal array projects is urgent. The public sector funds that have been allocated are conditional upon securing private sector investment as well.

“Due to the nature of public sector budget periods, the conditional funding has an expiration date, as we have just seen with DECC pulling back £10million it had provisionally allocated to the Marine Current Turbines (MCT) Skerries project, after the project was delayed beyond agreed deadlines.”

ORE Catapult continues: “If we assume that the remaining three initial tidal arrays require a similar amount of funding on average, then in the range of £72million to £129million is needed to get these arrays to financial close.

“There is a dearth of investors willing to take on the risks and unknowns (namely the short and long term performance and returns) associated with these projects, thus project developers are looking towards the public sector to facilitate funding solutions.”

Turning to wave, coverage of which is skimpy, ORE Catapult says: “In the wave sector, leading wave developers have reached full scale demonstration, and the EMEC test centre in Orkney has been central to providing a dedicated testing environment.

“However, further technology development is still required to demonstrate truly commercial devices which provide high confidence in performance and survivability, and potentially to reduce levelised cost of energy (LCoE) that utilities and project developers require to move forward with first array projects.”

The report mentions the need for around £50million of funding for two or three projects over a period of five years, but not much more.

Energy inquired as to whether ORE Catapult’s report was completed prior to the collapse of wave device leader Pelamis, or the decision by Siemens to shut down MCT and offer it for sale, or Aquamarine’s downsizing.

We were told there are references on pages three and 14, but none are specifically named.

Recommended for you