Renewables are beating fossil fuels on cost in island nations from the Pacific to the Caribbean, where governments are seeking to limit their exposure to volatile market prices.

“We’re so far-flung from the sources of fossil fuels that by the time they reach us, with all the shipping, you pay a substantial cost,” said Tommy Remengesau, the president of Palau, whose nation is located almost 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) east of the Philippines in the Pacific Ocean. “It’s an economic advantage for us to go for renewables.”

The remarks in an interview at the United Nations climate summit in Paris underscore the economic concerns of island nations. For many of them, obtaining and paying for fuel is a costly struggle that they must manage along with the threat of rising sea levels and more violent storms predicted because of global warming. That explains why these countries are among the more enthusiastic adopters of clean energy.

Palau is seeking to cut a $40 million-a-year fuel bill that consumes about a sixth of its economy, and it’s not alone. In the South Pacific, Fiji and Vanuatu are planning to generate 100 percent of their power from solar, wind and biomass by 2030. In the Indian Ocean, the Maldives is looking to renewables to reduce its almost total reliance on imported fossil fuels, and the Seychelles have set a 20 percent clean power target.

“We’re looking at options such as solar energy, wind energy and other technologies, because we are very much a fuel-based economy,” Maldives Foreign Minister Dunya Maumoon said by phone from the country’s capital Male. “We should be able to see a dramatic increase in the use of renewable energy.”

The Maldives’ climate plan shows why it’s hard for poorer countries to realize their ambitions. “High investment costs pose a major challenge to the introduction of solar,” the government said in its submission to the UN. The pledge doesn’t quantify the finance it needs.

Goals from each nation are spelled out in pledges submitted before the UN talks, where 195 countries are working on a deal to reduce greenhouse gases. While emissions cuts in small islands aren’t enough to even put a dent in the global total, economically they can pay off.

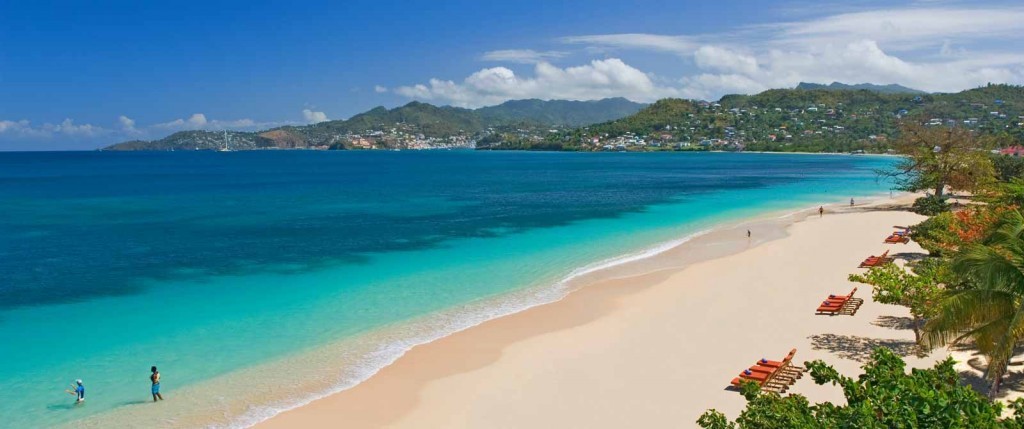

In Grenada in the Caribbean, they’ve done the math. Their carbon-cutting program through 2025 has a $161 million price tag. For that, officials hope to get 40 percent of energy from geothermal, 15 percent from solar and 4 percent from wind. They expect the plan to pay off.

“National savings are expected to be in the order of $300 million a year,” Spencer Thomas, lead climate change negotiator, said in an e-mail. “Substituting renewables for fossil fuels will enhance food and energy security, and improve balance of payments.”

Tumbling costs make the transition easier. Solar panel prices have fallen to 64 cents per watt this year from about $2 at the end of 2010, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. The cost of polysilicon, the raw material used in most panels, last month fell to $13.98 a kilogram, a record low that’s a quarter of the price in December 2009.

“Anywhere where you are competing for electricity generation with bunker or diesel fuel — except for places like Greenland or Iceland — you are better off with solar,” former U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu said in an interview. “If you are in an isolated place in a developing country you can use solar to charge your cell phone, to run your LED lights at night, to pump and purify water, to do a lot of things.”

There are still hurdles. The up-front capital costs can be prohibitive for small countries with limited budgets. According to Yvo de Boer, the former UN climate chief who now heads the Global Green Growth Institute in Seoul, for many investors, projects that are smaller than $50 million are hard to finance because transaction costs are too high.

“They are too small to deal with from a financial perspective,” de Boer said. “The up-front capital cost of renewables is high, but the operating cost is very low. You need to get over that hurdle.”

Some are moving ahead. Vanuatu expects to get power from solar, wind and coconut oil. In the Marshall Islands, almost 90 percent of energy needs are met by imported petroleum projects. It has been pushing renewables since 2008, when a price surge prompted a state of emergency.

“The fossil fuel era must draw to a close, to be replaced by a clean, green energy future,” Christopher Loeak, president of the Marshall Islands, said in a speech in Paris. “Carbon pollution is harming our health, stunting our growth, and suffocating our planet.”

Recommended for you