“You could have a platform running off of net zero methanol now – without any doubt,” says the Net Zero Technology Centre’s (NZTC) Lewis Harper, “if you had a facility in, let’s say in Aberdeen, that was using the industrial CO2 available as a feedstock”.

UK oil and gas assets need to slash their emissions dramatically, by 50% by 2030, to meet the targets of the North Sea Transition Deal (NSTD) signed with the UK government in 2021.

Power generation offshore is the big problem. Electrification, reducing the need for diesel and gas generators, is only going to work for some assets – meanwhile grid connection isn’t going to be available in many cases until it’s too late.

Many other assets therefore face a premature end to life because they can’t get a handle on their emissions.

But there’s a rising tide on alternative fuels – green methanol, in particular – which could provide an answer.

Siemens Energy, an industry leader, said green methanol or traditional methanol is the “most likely transition fuel” for aero-derivative gas turbines used for offshore oil and gas – and can provide a quick “win” much sooner than hydrogen, or full or partial electrification.

That’s a position backed up by the NZTC in Aberdeen, who say green methanol – e-methanol or biomethanol – is much more promising than ammonia and other fuels.

“The analysis that we’ve done up until now show there are no real technical barriers to conversion to use it offshore,” says NZTC project manager Charlie Booth.

“In terms of the handling of the fuel, the storage of it (NOV is working on a subsea storage solution in Norway), we can do all of that – and even the capex isn’t too bad.”

The main issues are supply, and the associated cost of methanol or biodiesel versus traditional fuel gas, of which more later.

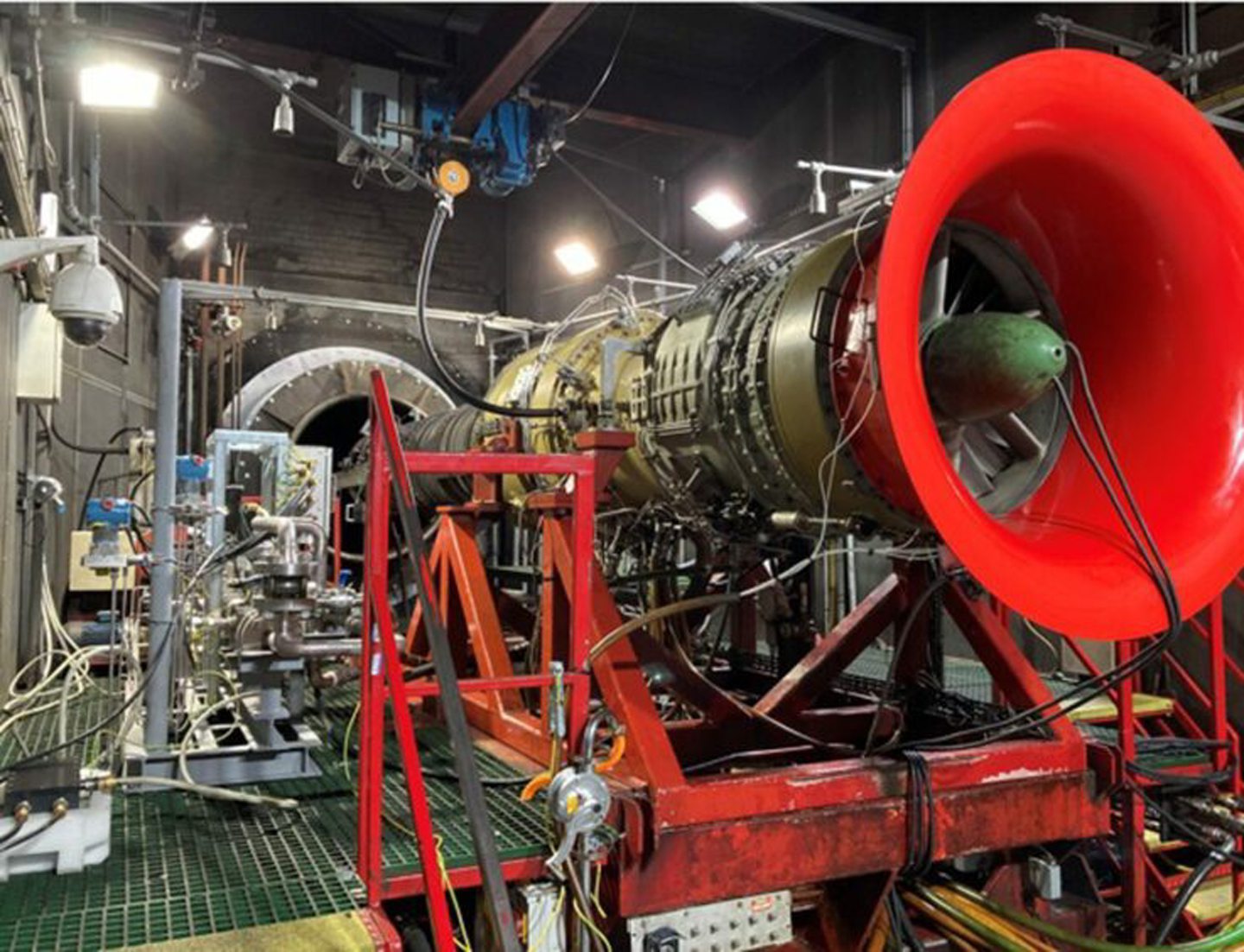

The NZTC carried out a test earlier this year with Siemens Energy – for a project brought on by the NSTD – on whether a 50-year-old gas turbine, like those used offshore, could take green methanol.

With minimal retrofitting – a change in the fuel injector system – the test worked, and found that green methanol could cut emissions by up to 75%.

Siemens Energy has 160 such turbines in the North Sea, according to the Methanol Institute, so “the potential there is really large”.

Each offshore asset in the UK North Sea is unique, and “all have to be considered individually,” says Mr Booth of the NZTC.

But he’s clear this can apply on a wide-scale: “Basically anywhere you’ve got onboard fossil fuel power generation”.

‘It is just a case of getting on and doing it’

Is it as easy as that? His colleague Lewis Harper, an emissions reduction project engineer, says yes.

“We’ve been saying for the past six months now, if you want to reduce 70% of your emissions, change your fuel. And it sounds ‘oh, it’s just as easy as that’.

“I’ve worked offshore for 10 years and yes, sometimes it is just a case of getting on and doing it. And this is one of those things that we actually can just get on and do it. It’s not one of those that goes in the bucket of ‘oh it’s not quite as easy as that’.”

It doesn’t have to be an immediate switch either. An operator could take “stepping stones” from traditional diesel, to a biodiesel blend, moving to full biodiesel, then onto e-methanol and biomethanol as the supply of those cleaner fuels becomes more available. Much of that optionality is due to methanol being a liquid.

Transport for methanol would be no different to how fuel is carried now for offshore vessels, and the environmental impact of a spill is far reduced compared to traditional fuels.

Meanwhile innovations are being made around flaring; emissions-busting firm M2X has a containerised system which can take flared gas offshore and convert it into methanol – preventing emissions from reaching the atmosphere.

Methanol tech for oil and gas

The technology is there, and certain North Sea assets have been looking into the use of biofuels, like EnQuest on its Kraken FPSO and Saipem on its 7000 crane vessel. In 2022, Odfjell Drilling successfully tested biofuel on its Deepsea Atlantic, cutting emissions by 80% versus fossil-based generation.

In Europe, the orders for newbuild dual-fuel methanol capability for offshore support vessels are rising – Orsted, RWE, Vestas, Sal Heavy Lift are among them.

Maersk, the shipping giant, launched its Laura Maersk methanol vessel last month – it has stuck with methanol because it knows the fuel works for retrofitting and for newbuilds. The firm has 24 others on order for delivery from 2024-27.

The technology is there for production assets in the UK, so why hasn’t this been done more broadly?

What’s stopping us?

Supply is “one of the biggest problems we’ve got,” says Mr Harper, when talking to UK North Sea operators.

“Straight away, they’re going to say ‘why am I going to tanker fuel from Holland, Denmark, or Iceland even, round to my asset, what, three times a month to refuel? When I could use my associated fuel gas?’”

By contrast, the NZTC “jumps” when a firm has assets in the Dutch sector, where they can point to “at least three or four different sites” to take green methanol.

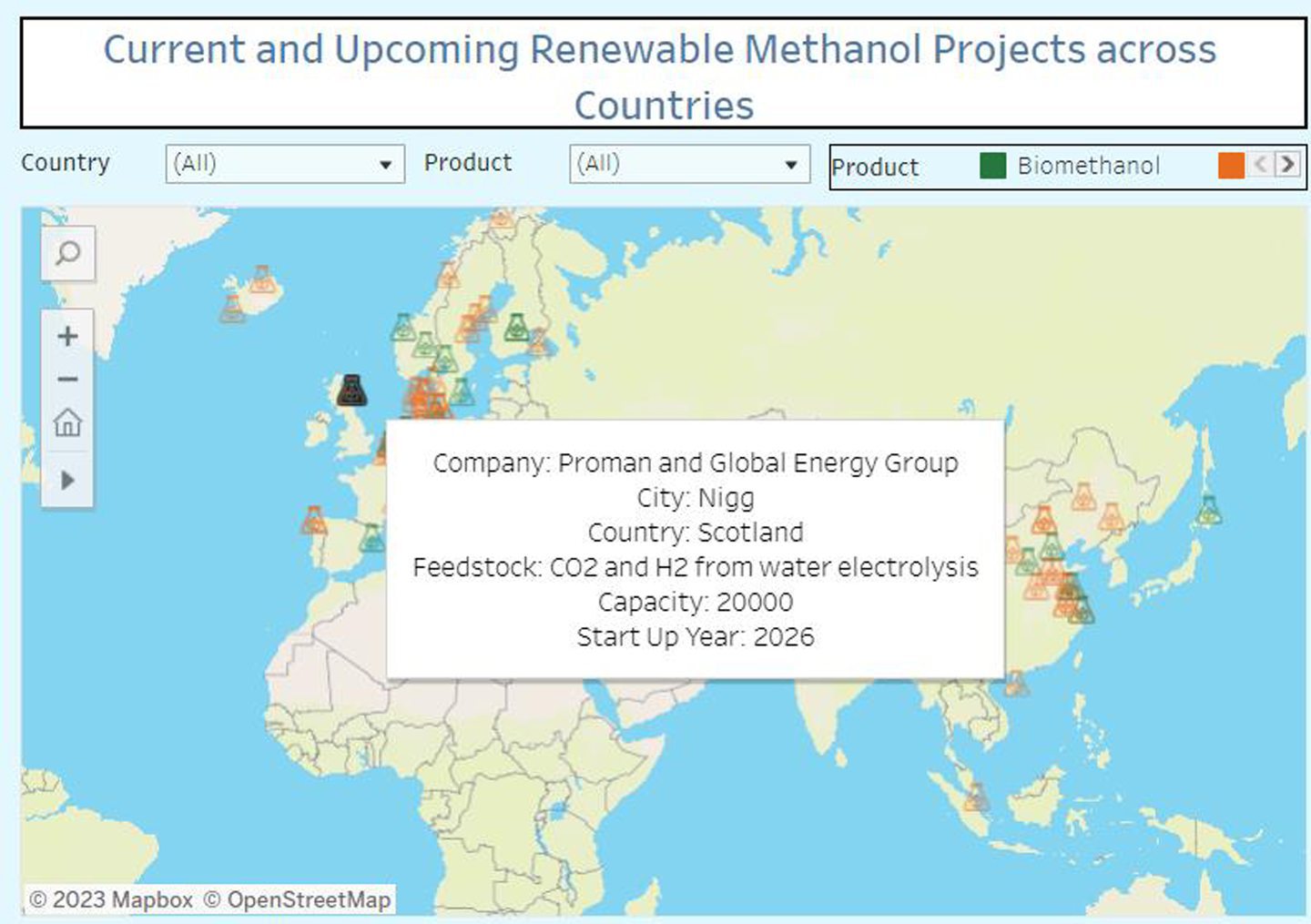

Unlike Europe, there are no green methanol production facilities in the running in the UK right now, according to the Methanol Institute.

Just one site had been mooted for renewable methanol – in 2021, Global Energy Group and Proman announced plans for an e-methanol site in the Highlands at the Nigg Oil Terminal.

However, nothing has been disclosed in the two years since, and the terminal is being decommissioned.

Global Energy Group and Proman did not respond to a request for comment.

In Denmark, by contrast, Maersk and renewable energy firm European Energy have built their own facilities – owning a slice of the supply chain to serve their vessels.

“There is a market there, if you can bring the cost down to a better level,” says Mr Booth.

That’s not just for oil and gas assets and offshore service vessels for wind, but for cruise liners and other vessels needing to cut emissions.

Another main barrier, Mr Booth adds, is a lack of understanding on how the carbon market in the UK applies to the use of these fuels.

“It’s something that we’ve identified that that we perhaps need to look into in far more detail.”

The NZTC’s “Energy Hub” is carrying out studies right now on improved supply of green methanol.

Costs and options

Greg Dolan, CEO of the Methanol Institute, said eight million tonnes of renewable methanol will be in the market by 2027, and around 200 new-build vessel orders using the fuel are on the way.

On cost – there is nuance on how it might apply to UK oil and gas assets, and it depends on the extent to which operators blend the fuel.

They might take a portion of cheaper “grey” methanol from natural gas – still with a better CO2 profile than diesel – and blend it into more costly “e-methanol”, for example.

“Because methanol is a liquid and ambient temperature pressure, it’s the same molecule, whether it’s grey, blue or green, right – so you have the ability to blend it,” says Mr Dolan.

“You can take some of the higher cost biomethanol and e-methanol and blend it with conventional methanol from natural gas which actually costs less than water. I mean, right now I think the selling cost of methanol in the US is less than a dollar a gallon.

“You have the ability to essentially dial in whatever carbon intensity you want for the fuel by blending the grey, blue, or green against your ability to pay or your willingness to pay.”

Methanol for oil and gas: When will the UK get going?

Why aren’t there facilities for this in the UK? Mr Dolan thinks it’s a “chicken and the egg” situation on when supply or demand will come first.

UK ports – linked to offshore wind projects – could be ideal for production of E-methanol, he says, though the barrier there is costly electrolysers, which Scotland lacks manufacturers for.

Biomethanol, on the other hand, is in our market now – a small portion of it is in our petrol – and could be produced at varying scales due with the variety of CO2 feedstocks available, from landfills to dairy farms.

The infrastructure is relatively simple, modular and scalable. For small vessels, it can even be delivered directly via fuel truck.

Shifting to the fuel “is a technology development” but one that is available right now for many offshore installations.

“Offshore platforms really do need to cut their emissions, and the big driver for emissions is burning the associated natural gas, to the point where you’re going to see platforms retired really before their end of the life just to control emissions.

“So if you can find a way to reduce those emissions with a cleaner fuel like methanol, then you can extend the life of those assets and keep them operating again.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by NZTC

© Supplied by NZTC © Supplied by NZTC

© Supplied by NZTC © Supplied by EnQuest

© Supplied by EnQuest © Supplied by Methanol Institute

© Supplied by Methanol Institute © Supplied by NZTC

© Supplied by NZTC © Supplied by Methanol Institute

© Supplied by Methanol Institute © Supplied by Saipem

© Supplied by Saipem