The last 12 months have been a busy time for the carbon capture storage space in the UK with the winners of the much-anticipated Track 2 process being announced and the first licencing round in the space being delivered.

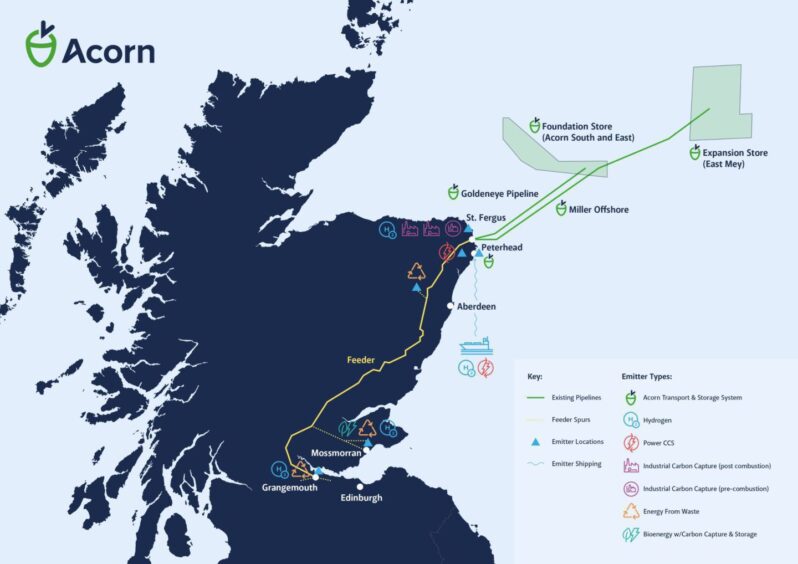

In July, prime minister Rishi Sunak announced that Aberdeenshire’s Acorn project and Humber’s Viking had been selected as part of a £1 billion Track 2 funding competition.

Acorn, at the St Fergus gas terminal, lost out on the contest’s first “track” of funding in 2021, with projects in Wales and Teesside selected instead, and earlier projects in Peterhead being cancelled.

With the Track 2 process helping set up the project that will prove to be the backbone of the “Scottish Cluster”, the process is not sustainable, says Alistair Macfarlane, manager of UK carbon transportation and storage at UK regulator the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA).

He said: “Continuing to fund projects in the way the Tracks 1 and 2 are doing isn’t something that is sustainable, you have to find a levelling off on the support that gets given.”

Currently, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) is compiling a report into this that should be published by Christmas. The NSTA and industry has been engaged in this document with “a couple of roundtables” being held, Alistair Macfarlane told Energy Voice.

Mr Macfarlane explained that in this the DESNZ will “definitely have some signals to what they think needs to happen to move things more to the merchant model approach that some other countries are doing.”

However, it is not easy changing the way in which the Track process is structured, there is a lot to think about when it comes to ensuring the package provides the right levels of support for new carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects.

“I think each of the track ones has got cement manufacturer, they’re obviously going to get support dealing with their emissions,” Macfarlane said, “but there are not only two cement manufacturers in the UK.

“There aren’t, so you distort a bit of the market by giving support if you don’t also support others.”

Despite the challenges, changes must be made to how the Track process works if it is to see longevity and help deliver the UK’s hefty CCS ambitions.

The UK government is currently targeting the capture of 20-30 million tons of carbon dioxide per year by 2030.

“I think everybody commonly accepts that it’s not a copy of Track 1 when you’re on Track 26 or something like that,” Mr Macfarlane commented.

“It’s going to have to be it for purpose, and it’s going to have to enable European imports as well because Track 1 and Track 2 are just focused on UK emissions really.

“The next big step is, how do we bring in EU emissions and how do we build the framework that enables that?”

Accounting for ‘failure rates’ with future licencing rounds

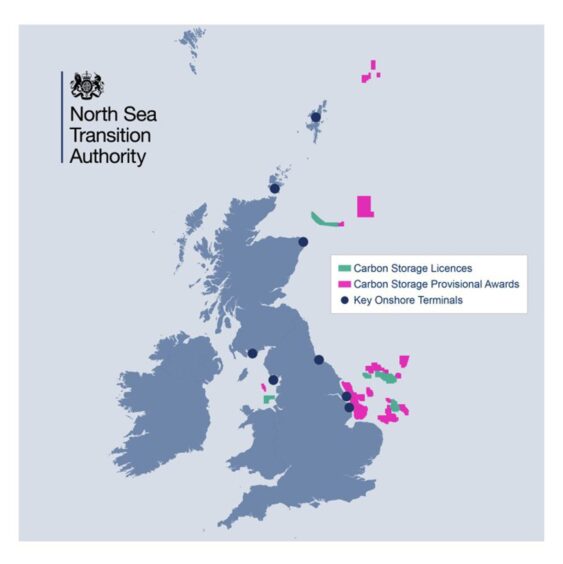

Earlier this year the NSTA announced that 14 companies had been awarded 21 carbo storage licences in UK waters.

Thirteen areas were offered off the coast of Aberdeen, Teesside, Liverpool and Lincolnshire in the southern North Sea, central North Sea, northern North Sea, and East Irish Sea as part of the process, which kicked off last summer.

When asked if the ball was rolling on the next licencing round for CCS, the NSTA’s manager of UK carbon transportation and storage gave the short answer: “no”.

However, that does not mean there is no progress being made towards bringing more CCS projects online.

Mr Macfarlane said: “We’ve got to incorporate the learnings we’re getting from the journey towards grant permits and then and the delivery of projects.”

That being said, we are not going to be waiting “six years until the next licencing round”, he added.

“It will be a lot less than that, but you just have to look at the timings of the phases.”

The NSTA’s manager of UK carbon transportation and storage wanted to make one point “very clear” and that was, if the UK is to meet its targets for storage by 2050, the regulator will need to account for failure rates.

“That’s not once the store is up and running, that’s getting it to become a store,” he explained.

Mr Macfarlane explained that to account for this “you need to have a lot more potential projects in flight and we know that, but you want to make sure it’s the right ones.”

However, a recent report by Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis (IEEFA) found that the UK’s CCS capacity is likely to fall short of 2030 target.

IEEFA’s analysis showed that current CCS cluster capacity will not meet levels set out by the Climate Change Committee (CCC) in its Sixth Carbon Budget.

Currently eight projects are set to receive support across the two ‘cluster’ schemes – East Coast Cluster and HyNet – which secured backing under the 2021 “Track 1” sequencing process.

These findings were not representative of the UK’s CCS landscape, said Alistair Macfarlane.

He said that the IEEFA “conveniently ignored the Track 2 projects which is a bit of a miss because they are critical to helping meet that target.”

Andrew Reid, author of the report and a guest contributor at IEEFA Europe responded to these claims: “There are 10 capture projects associated with the Acorn and Viking sites, and when the government announces which they are going to progress to negotiations for support, we will re-run the analysis.

Mr Reid added: “We really need to wait and see what happens as there is insufficient detail to review how Track 2 will impact the make-up of CCS projects within the UK.”

UK government support for CCS and North Sea decommissioning

Moving forward, the industry will be receiving support from the government to transition oil and gas assets into CCS infrastructure to help meet targets.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt announced in his recent autumn statement that the UK government aims to remove the tax barriers to oil and gas assets being repurposed for use in carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) projects.

The review said these payments will cover the oil and gas company’s share of the decommissioning liability of the repurposed asset and be due tax relief of equal value to the relief available for ordinary decommissioning activities.

According to the Treasury, the changes will allow for “levelling the playing field between decommissioning and repurposing and supporting the transfer of assets”.

In addition, the review confirmed that while the current Decarbonisation Investment Allowance – which provides temporary, additional tax relief for decarbonisation investment – will cease after 2028, the permanent tax regime will continue to offer tax relief of £0.4625/£ on investment, including for decarbonisation.

Looking at CCS in the UK by December 2024

With debate around whether the UK will meet its CCS targets, Alistair Macfarlane looked ahead to what he sees in the sector’s history.

When questioned about the state of the market by December 2024, Mr Macfarlane answered: “I hope we have two permitted projects and that we are quite a bit further down the road on the Track 2s. They have ambitions to be storing very quick.

“And the vision work matured enough so people got clarity over what’s next and they can start cracking on for the next 16 licences that have nothing to do with the current clusters.”

Making moves towards the next round of licences is “quite important,” said Mr Macfarlane as firms have “work programme commitments over the period and while that uncertainty exists around ‘how are we going to monetise this?’, they aren’t going to want to spend lots of money and do lots of activity.”

For the current projects to get moving in the way that Mr Macfarlane predicts, the NSTA needs to finish evaluations of the sites, something he is “100% confident” will happen.

However, for the rest of his prediction to be delivered, there are a number of factors to contend with. As he explained: “For everything else, you’ve got to think business models need to be agreed and negotiated by DESNZ, there’s the potential for a general election that could get chucked into the mix there as well, what will that do to the decision-making process for other bodies?

“That, I can’t tell.”

He said that despite what 2024 holds, the NSTA will “adapt” and that “the appetite from industry and those two Track 1 operators, they’re desperate to be able to get the go-ahead.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Storegga

© Supplied by Storegga © Supplied by Storegga

© Supplied by Storegga