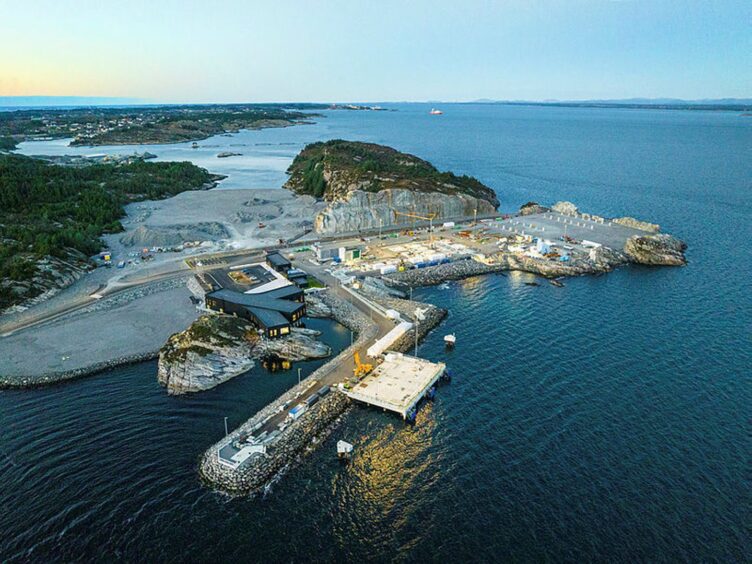

A dozen glistening storage tanks on a windswept island in the North Sea are one of the few visible signs of a costly experiment aimed at making a tiny fraction of Europe’s industrial pollution disappear.

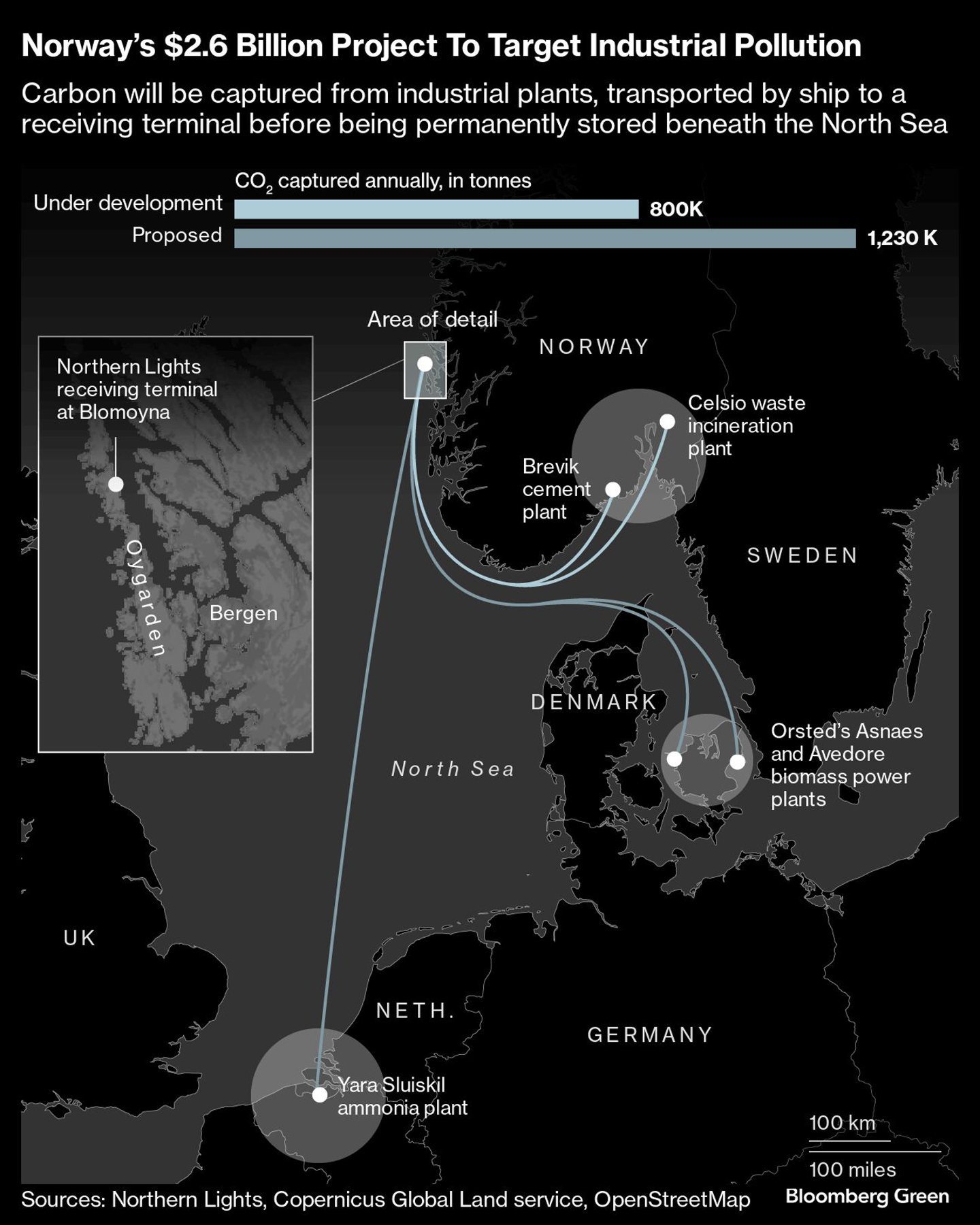

Part of a $2.6 billion network, the facility on Norway’s Blomoyna is set to pump climate-warming carbon dioxide from manufacturing sites in the Netherlands and elsewhere into an untouched saline aquifer deep below the seabed. The first injections could start as early as next year and pave the way for a new international trade in industrial emissions.

That is if the pollutant can be neatly captured at smokestacks, legally shipped along an untested transit network and reliably stored at a significant scale. Those are big ifs, but desperation by Germany to support manufacturers is helping to fuel the momentum.

“Offshore storage in the North Sea is inherently more costly than onshore,” said Jens Burchardt, a Berlin-based partner with Boston Consulting Group. “The solutions currently under discussion pose a threat of making the technology prohibitively expensive.”

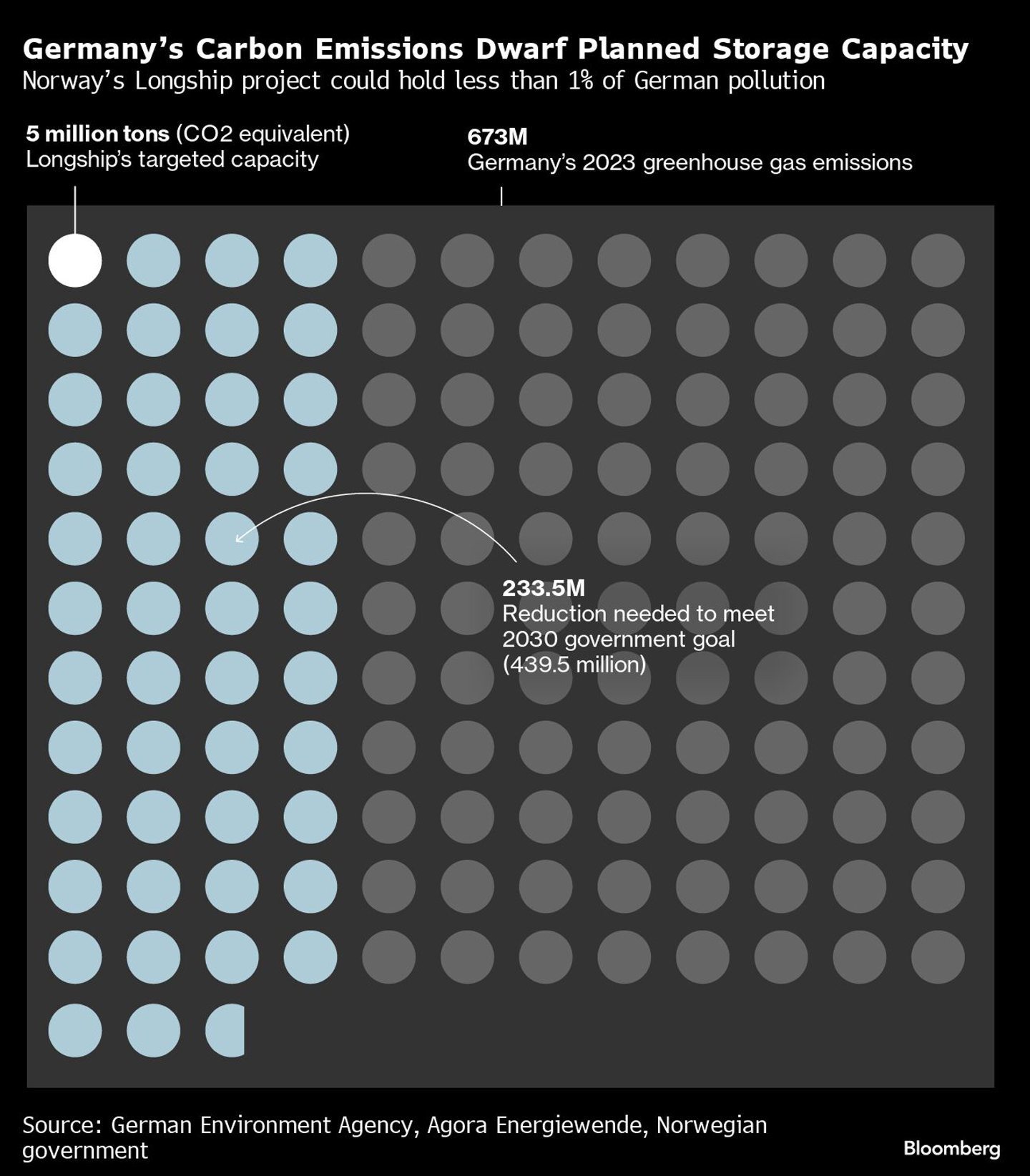

But such concerns aren’t deterring backers of a European network for carbon capture and storage (or CCS), including Germany. The region’s biggest polluter — which spews out more emissions than the next two countries combined — is now counting on the technology as its industrial base struggles with challenges from high energy costs to Chinese competition.

Abandoning previous objections, the government in Berlin is now throwing its weight behind the initiative on the condition that it only be used for industrial sectors like cement, fertilizers and steel and not to burn more oil and gas, according to Ingrid Nestle, a lawmaker from the co-ruling Green party.

“We are open for usages in hard-to-abate sectors,” said the 46-year-old, who in the past had joined protests against plans to store carbon dioxide below the soil of her constituency in northern Germany. She’s now helping to rewrite laws to allow carbon to be transported across borders and then buried under the sea.

While Germany may want to restrict the technology to justify a political u-turn, the European Union is backing wider usage. According to a proposal from the bloc’s executive arm, as much as 450 million tons of CO2 will need to be captured annually by 2050 to achieve net-zero goals, including 100 million tons from generators powered by fossil fuels.

Amid cost and feasibility issues, current plans aren’t even close to those volumes. That makes the project in Norway an important test, with ramifications for Germany as well as the global oil and gas industries.

The technology involves complex systems that isolate CO2 from factory emissions. The pollutant is then compressed, dried and cooled into a liquid state so it can be loaded on to a ship or sent via pipeline to a storage terminal like the one on Blomoyna.

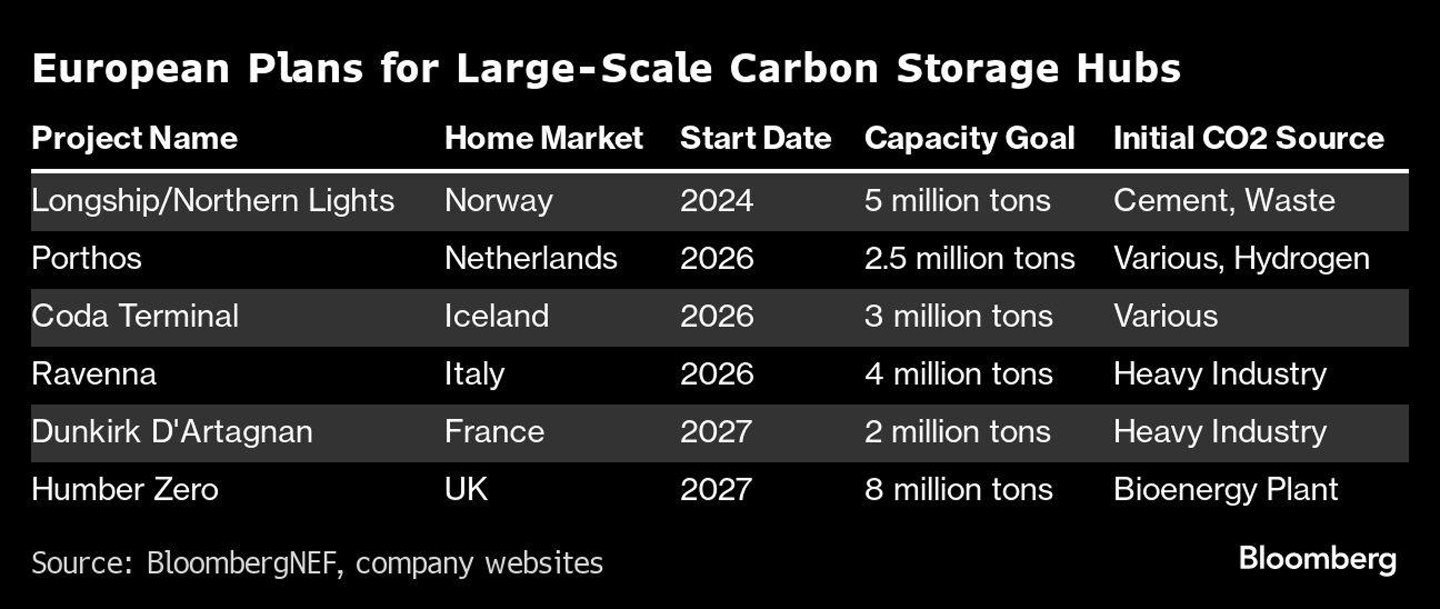

Worldwide, there are plans for about 30 large-scale carbon capture hubs offering transport and storage, according to BloombergNEF. Most are linked to fossil fuel companies, and only a handful are under construction or in advanced development.

Norway’s 27 billion-krone ($2.6 billion) Longship project is due to be the first CCS hub in operation. The receiving terminal at Blomoyna will hold the carbon dioxide in 12 tanks — each about as tall as a 10-storey building and together capable of holding 8,000 cubic meters. The liquefied gas will then be pumped via pipeline to a reservoir 2.6 kilometers (1.6 miles) beneath the floor of the North Sea.

The plan — two-thirds financed by the Norwegian government — is part of the country’s pivot away from fossil fuels and toward cleaner commodities like blue hydrogen.

The project also reflects Norway’s decision to de-couple its CCS strategy from oil and gas, according to Ingvild Ombudstvedt, CEO of Oslo-based IOM Law, which specializes in CCS issues. After failing to successfully deploy the technology at two natural gas facilities over a decade ago, “Norwegian authorities went back to the drawing board,” she said.

Controlled by Equinor ASA, Shell Plc and TotalEnergies SE, Northern Lights —the transport and storage component of the CCS hub — aims to connect the Blomoyna terminal and its North Sea reservoir via ship with manufacturers across Europe. The first of four vessels is due to be delivered next year.

“I think people imagined CCS as a network before, but it wasn’t possible because the storage and transport options weren’t available,” Grete Tveit, Equinor’s head of low-carbon solutions, said in an interview in November.

The Norwegian oil giant has been injecting CO2 into the seabed at its Sleipner West field since 1996. A second reservoir at the Snohvit field in the Barents Sea was added in 2008. Both projects faced teething issues, including interruptions during injection and measures that didn’t fully strip out the carbon dioxide. But backers insist such issues are fixable.

“We know the technology works, but should still expect challenges in the first year,” said Philip Ringrose, a professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. There are a lot of moving parts to divert the CO2 from the atmosphere to the ocean floor. “Things have to line up,” said the geologist, who worked on Equinor’s Sleipner and Snohvit projects.

At Blomoyna, work is 90% finished. On a recent visit, workers preparing to pour fresh cement stood ankle deep in snow overlooking a tunnel dug through the island and out into the fjord. In March, the final leg of a 100-kilometer transport pipeline will be laid out to the reservoir. The project has attracted attention, with 6,400 people visiting since 2021.

But the sector is littered with failed initiatives, and costs for users remains a big hurdle. Belgian lime producer Lhoist SA — which works on various carbon-capture projects — says its models show that the carbon price would have to double if not triple from its recent range to make a business case for storage, without public subsidies.

Nevertheless, some manufacturers are ready to take the plunge. Early last year, UK’s INEOS Group Holdings SA and Germany’s Wintershall Dea AG were the first to transport carbon across national borders — from Belgium to Denmark.

Fertilizer giant Yara International ASA and Danish wind-power company Orsted AS recently signed long-term contracts with Northern Lights. And around 100 companies have asked Germany’s grid operator OGE to hook them up to a CO2 pipeline network.

Heidelberg Materials AG is due to be the first to send emissions through the Longship network, targeting some 400,000 tons of CO2 annually from its Brevik cement factory west of Oslo to Blomoyna. By removing the carbon, the German cement maker can produce an exclusive greener version.

“This will be a one-of-a-kind product with unique characteristics that will demand a completely different price point,” said Chief Executive Officer Dominik von Achten.

If it all works out, Norway expects to be at the center of a self-sustaining market within a decade and Europe’s industrial polluters will have a lifeline for the low-carbon era.

German Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck, a Green politician who’s been forced into numerous compromises in his role overseeing economy and climate policy, visited the Brevik plant on a snowy day in January last year. “In my view, I would rather have CO2 in the earth, than in the atmosphere,” he said.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg © Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg © Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg