Storegga is behind multibillion-dollar emissions-busting plans for north-east Scotland, including the Acorn carbon capture and storage (CCS) project. CEO Nick Cooper sits down with Energy Voice to assess the landscape.

Nick Cooper was waiting on a train back in October when crucial news arrived on the government’s aptly-named “Track 1” awards.

His company Storegga had made a “competitive, compelling” proposition for the Scottish Cluster, in which the Acorn development near Peterhead is the backbone, to be selected as one of the first two developments in the UK, taking a share of £1 billion funding.

“When the decision was announced, I was so surprised I almost . . . I was waiting at a train station and I almost fell on the tracks. And I don’t shock easily.

“It was a massive shock, not because we lost a competitive process but because there were aspects – and there still are – of the Scottish Cluster and the Acorn project specifically which offer benefits not just to greater Scotland but to the greater UK and to the other clusters.”

Anyone following industry or local press will be well aware that Acorn was picked as a “reserve” in Track 1; “running up and down the touch line, but not on the pitch” as Cooper puts it.

“We’re on the verge of a commercial European CCS industry”

“You’re never complacent going into a competitive process”, he says, and Storegga had planned for a negative outcome. But it’s the strength of the fundamentals of the Scottish Cluster which gave rise to a reasonable sense of confidence in its position.

Be it on emissions storage or jobs, the mooted figures are clearly attractive.

The first phase of Acorn – a multi-billion pound project – will see 5-6 million tonnes of CO2 stored, but there’s geological potential to “easily” ramp that up to 20 million tonnes per year and even double that again to 40 million tonnes, matching the current global total.

Utilising those carbon stores, and the potential to ship emissions in from elsewhere in the UK and even Europe, is a key strength of the project to get the industry up and running.

“I think there’s a lot of entities in government that recognise we need resilience in the early phases of this industry, because there’s a lot of bottlenecks in the system as you build any infrastructure class out and one of the major advantages of Acorn is it can bring a lot of volumes from elsewhere and support other clusters to get going.

“Not only does it have its own merits; unique things like direct air capture and shipped volumes and central belt, power stations, security of power supply, all of those aspects, but it also offered resilience and de-risked the government’s 2030 targets.”

Delivering a strong baseline “and more”, then, but it’s the latter that might have got lost in the government assessments, Cooper conceded.

Jobs-wise, some 21,000 roles are expected to be created for phase 1, directly and through supply chain.

“A simple proxy for jobs would be: it’s 21,000 for 5-6 million tonnes, imagine what 20 million tonnes would do, across various sectors and the supply chain”, says Cooper.

Depending on whether you look at Peterhead, Greater Aberdeenshire, Scotland, the UK and beyond, he has high hopes on the industrial benefits for this multi-user carbon disposal market.

“I think the positive shockwaves are going to be at least as strong as when the oil and gas industry first turned up here.

“Not Storegga solely, but in terms of the whole supply chain and the attendant first and second order developments that will follow these carbon chains.”

So where does the reserve status leave the Scottish Cluster for timing, having previously been mooted for first injection by 2026?

Cooper says it is still “just about possible” to hit that 2026 target but “the longer the government leaves us in this ambiguous situation, the later we can start”.

He adds: “if we are asked by the government to participate in another track process, there’s Track 2, and then to abide by those rules, we may be asked to start two or three years later.

“I think from a commercial perspective that’s criminal, because the commercial opportunity is there.

“I think from a climate perspective it’s more than criminal that we should be sitting on our hands when this is such an obvious thing to get on with now.”

Asked whether that delay is the most likely scenario: “We don’t know but that could well be the case.”

The UK energy minister Greg Hands has promised more details on Track 2 this year, but timing, for the UK and worldwide, is key.

According to the Global CCS institute, some 2,000 large scale facilities are needed to meet climate targets, with just 27 currently fully operational (though 135 are in the pipeline).

The world effectively has just 28 years to go through the process of reproducing the entire energy complex.

“That is a frightening task, a daunting task in many ways”, says Cooper, “but you’ve got to start somewhere.

“Unfortunately most people are still approaching this as if it’s a peacetime scenario.”

More of a “wartime mentality” is needed see the urgent action that is needed, he argues.

The commercial side of the coin is also demanding urgent action. With the carbon price rising to around £80 a tonne in the UK, many emitters are seeking a solution but can’t find it.

“Europe is potentially facing a chronic shortage of storage, as is the UK. Not longer-term, but certainly in the second half of this decade through the first half of next decade.

“So if you’re an emitter in the UK and continental Europe, you’re scratching your head. I know of European emitters that are planning on taking CO2 to the US because the US is moving faster.”

Storegga, and many in the north-east business community are thereby arguing the case that all these projects, Track 1 or otherwise, should be allowed to progress immediately.

“The world has moved dramatically in terms of the carbon price and the net zero imperative in the last five to 10 years.

“We’re on the verge of a commercial European CCS industry, we should just let it happen without trying to pick winners and losers.”

Storegga itself seems to have moved dramatically in recent years, going from a “blank sheet of paper” pre-2019 to a vehicle “purpose-built for the energy transition”.

The grand plans are backed up by strategic investors with pockets big enough to scale them up; Australian banking giant Macquarie, Mitsui, GIC, M&G and, most recently, European gas infrastructure operator Snam, are all in that number.

Although CCS has the characteristics of an oil and gas business in reverse, it is lower-margin, so a big focus now is on costs and standardisation “the things that wind and solar have demonstrated”.

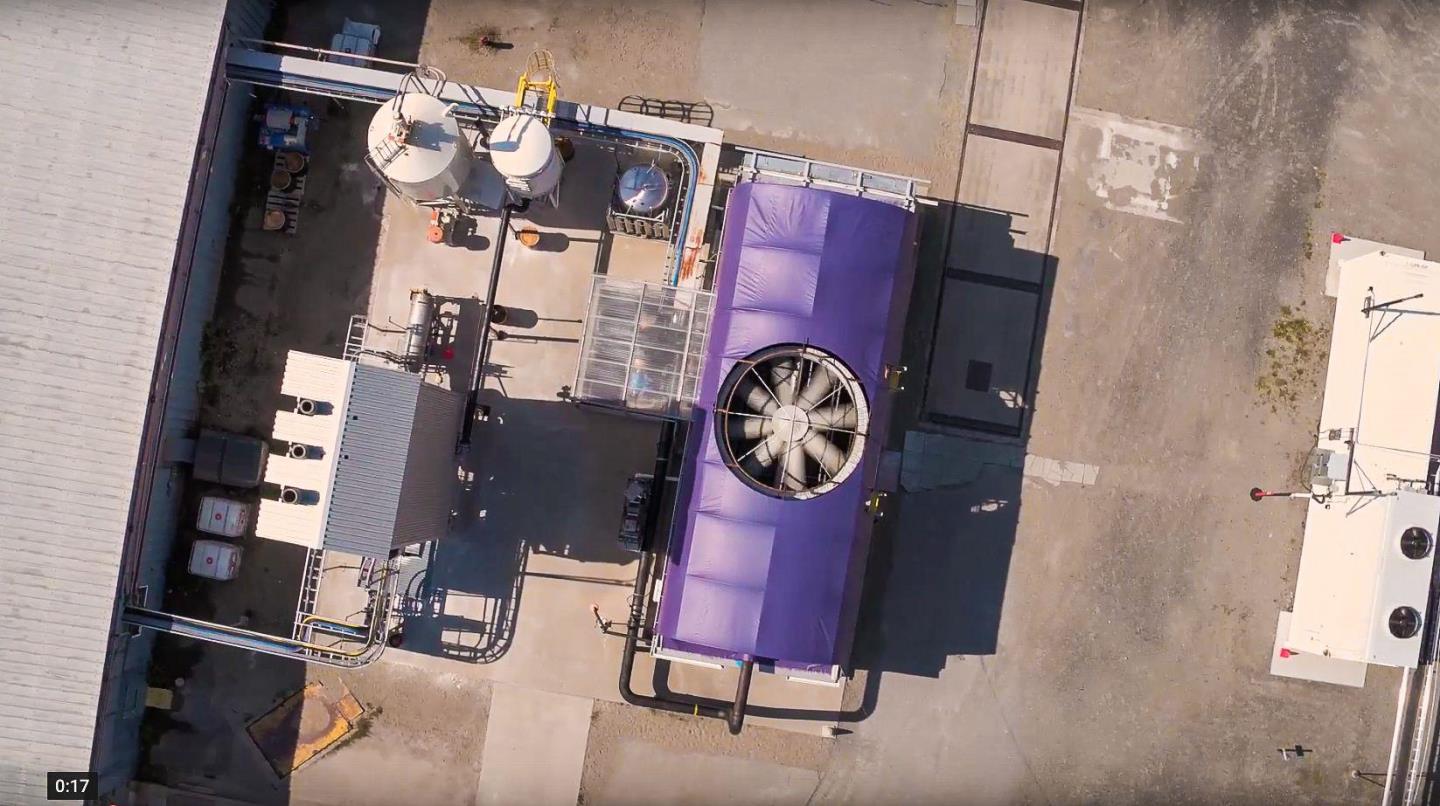

One aspect of Storegga’s plans which are expected to see a dramatic reduction in cost is Direct Air Capture (DAC).

Described like a “vacuum cleaner for the atmosphere”, it captures the public imagination, and that of policymakers, more than hydrogen and more than CCS.

Storegga hopes to have a 1 million tonne DAC plant operational from 2026, if government gets behind it.

“That will be Europe’s first at massive scale DAC project. Pretty big deal.

“We’re also scouting two or three other sites elsewhere for doing the same again.”

For Cooper, one of the more stark figures to arise from COP26 was that nature-based solutions can only tackle around one-third of the carbon offsetting measures required, setting the case for DAC and bioenergy into CCS.

He was at first sceptical there’d be enough early adopters tro get it off the ground but was “delighted” to be proven wrong.

Storegga is partnered with Carbon Engineering on the scheme – a Canadian firm already working with the likes of Occidental in the US on DAC.

Occidental plans 70 such facilities by 2030, giving strong hopes for economies of scale.

“This is a cracking opportunity in the UK to build a supply chain to be part of that wave and to learn from what we did right from the offshore wind pioneering and correct the bits we didn’t do so well – so the supply chain – and just crack on with it.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Shell

© Supplied by Shell © Supplied by Storegga

© Supplied by Storegga