After years of discussion and disappointments, amongst them at least two false dawns, the UK’s carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS) industry is starting to fall into place.

The North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) recently revealed that 12 companies had bagged 20 offshore storage licences in the regulator’s first-ever carbon licensing round.

While the announcement itself was somewhat scant on detail, the regulator hailed it as an “exciting and important day” in the UK’s energy transition.

Meanwhile, the ‘Track 2’ piece of Westminster’s CCUS funding competition continues to roll on.

Still, the UK is some way from first injection, and even further from the ambition to capture and store up to 30 megatonnes (Mt) of carbon emissions per year by the end of the decade.

More needs to be done to shore up business models that will allow emitters to use what is, currently anyway, an expensive means of abatement.

Several models in development

“There are a number of ‘business models’ being developed for CCUS, each designed to provide operational support to cover the additional cost of operating with CCUS, whether it’s an industrial plant, a power plant or a hydrogen production plant,” says Ruth Herbert, chief executive at the Carbon Capture and Storage Association (CCSA).

“Business models are also being developed for engineered greenhouse gas removals such as bioenergy with CCUS and direct air capture. Each one has a different basis for the strike price and the reference price for the difference payment, depending on the market it is playing in.

“For example, the power CCS business model is a dispatchable power agreement (DPA), which aims to dispatch gas-fired power stations with CCS after renewables but ahead of unabated gas. The Industrial Carbon Capture (ICC) business model is a carbon-based CfD, linked to the current Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS).”

In the main, contracts for CCUS will operate outside the power market, setting them apart from the CfD scheme that has successfully reduced the cost of offshore wind in the last decade.

Cluster sequencing setting schedule

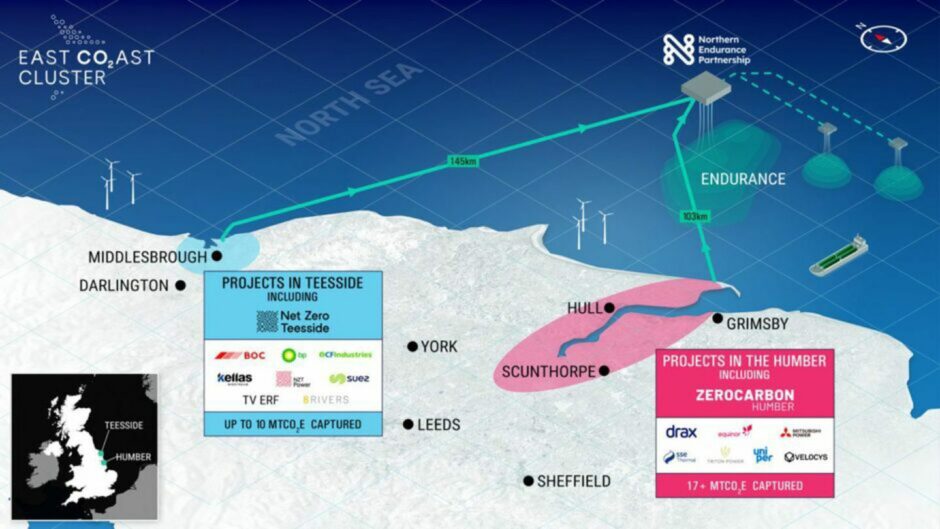

As it stands, only eight projects within the ‘Track 1’ clusters – HyNet in the North West of England, and the East Coast Cluster – are able to move forward to bilateral negotiations over price and contractual terms on ICCs, DPAs and hydrogen models.

For CCUS operators, the key will be the carbon price; the higher the price, the less operational support will be needed from the public purse.

Capture projects will also pass on a proportion of their operational support payments to network operators for taking away emissions.

Ms Herbert added: “If more volume is added to networks then the costs of transport and storage (T&S) per tonne of CO2 could come down. The users of the network pay the T&S company a fee to transport and geologically store CO₂, with the T&S company making a reasonable regulated return on investment.

“The Economic Regulatory Regime (ERR), proposed to be regulated by Ofgem, sets the regulatory framework, such as allowed revenues, outputs and incentives – this is supported by a suite of mechanisms.

“In the early stages of CCUS, T&S fees will be a pass through cost in user business models funded by the exchequer and consumers. Construction of early networks is also supported by part of the £1 billion CCUS Infrastructure Fund.”

Learnings from elsewhere

Given that CCUS is still in its infancy, and there are still those who question its efficacy, there is limited ability to copy and tinker with proven models from overseas.

In the Netherlands, there is a scheme called the SDE++, which funds the operational costs of carbon capture projects through a levy on consumers.

It enables CCUS facilities to bid for carbon-based CFDs, similar to the UK’s proposed ICC business model.

Notably, such schemes don’t create a new carbon market, rather they are linked to the current ETS, which “already recognises CO2 captured and stored from would-be emitters as ‘not emitted’, where storage is provided by an NSTA-licensed operator”, explains Ms Herbert.

She added: “However it also needs to recognise the value of carbon dioxide removals from the atmosphere. Equally important is that there is alignment and mutual recognition between the UKETS and the EUETS, so that CO2 stored in the UK is recognised by the EU as not emitted. The UK has huge potential for offshore CO2 storage and will be well-placed to export storage services to help other countries decarbonise if we move quickly to develop our infrastructure.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by CCSA

© Supplied by CCSA © Supplied by BP

© Supplied by BP