A new report finds that the UK’s carbon capture and storage (CCS) capacity is likely to fall short of 2030 targets and complains of ‘disproportionate’ support for blue hydrogen schemes over electricity generation.

Analysis by the Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis (IEEFA) finds that current CCS cluster capacity will not meet levels set out by the Climate Change Committee (CCC) in its Sixth Carbon Budget.

Currently eight projects are set to receive support across the two ‘cluster’ schemes – East Coast Cluster and HyNet – which secured backing under the 2021 “Track 1” sequencing process.

Included in these are power projects such as Net Zero Teesside, as well as industrial sites such as Hanson Padeswood Cement Works, Viridor Runcorn Industrial CCS and HyNet Hydrogen Production Plant 1 (HPP1).

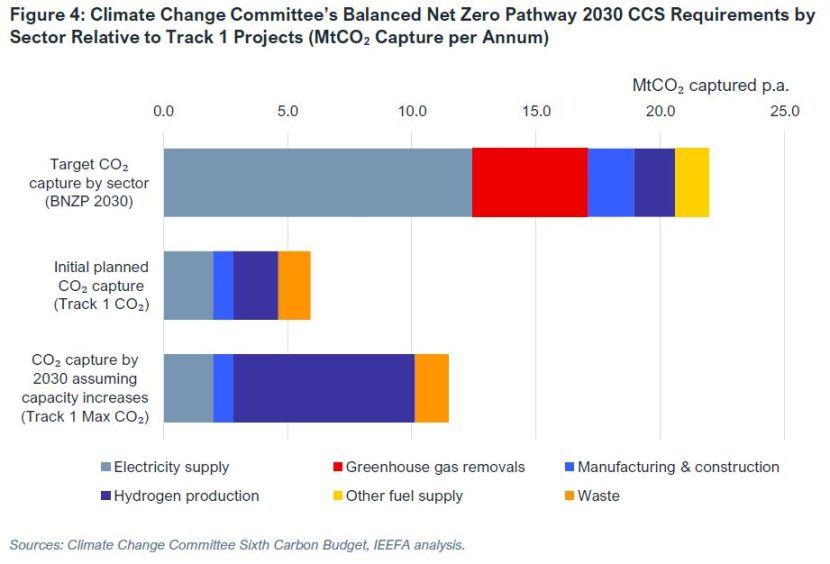

The eight projects are expected to capture around 6 million tonnes of CO2 per annum during their initial phase, meeting only 27% of the CCC’s 2030 forecast of around 22m tonnes.

“Assuming capacity is increased from follow-on phases before the end of the decade, the projects will continue to fall short, meeting only 52% of the carbon capture target,” the think tank said.

The government meanwhile aims to capture and store between 20-30 million tonnes per year by 2030, and over 50m tonnes by 2035.

To get there it has pledged a £20bn funding package over the next 20 years, which Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said would help pave the way for schemes “everywhere across the country” by 2050.

A further two “Track 2” clusters – Acorn and Viking – are also set to receive support, and contain 10 prospective CCS-linked projects within them. However these were not included in the IEEFA analysis due to the early nature of discussions, and a lack of indication as to which projects will be included.

Together these schemes could store an additional 15 million tonnes per year by 2030, bringing targets within reach, though timelines for delivery will depend on current negotiations with government.

‘Excessive’ focus on blue hydrogen

At the same time, the authors point to a “severe lack of support” for CCS schemes which help decarbonise electricity generation and/or are being retrofitted to gas-fired power – putting the UK’s target for a net-zero electricity sector by 2035 at risk.

As it stands, Track 1 projects are set to meet only 16% of the 12.4m tonnes per annum required to support the decarbonisation of electricity supply by 2030, casting a shadow over plans for all gas power generation to be abated or have CCS retrofits by 2035.

Meanwhile, CCS for hydrogen production will overdeliver, reaching as much as 444% of its CCC target.

Notably however, IEEFA also finds that an emphasis on power projects over hydrogen at the Acorn and Viking clusters would “reverse the current gap in decarbonising power supply as per the CCC projections.”

“It is clear that the UK government needs to focus its attention on supporting CCS projects that increase decarbonisation of electricity supply while the UK energy mix transitions to lower-carbon sources,” said Andrew Reid, co-author of the report and a guest contributor at IEEFA Europe.

“A disproportionate amount of support is currently targeting blue hydrogen production, which not only risks meeting the CCC targets but is questionable longer term as the UK increases renewable power generation and the potential for green hydrogen production.

“The announcement in July this year increasing the number of clusters that would be considered for support to include Acorn and Viking presents an opportunity for the government to prioritise power generation projects over blue hydrogen, getting back on track with the Climate Change Committee’s projections,” he added.

Danger of fossil fuel “lock-in”

The report also points to the “significant technical, economic and environmental risks” across various CCS applications, and the poor performance from existing projects.

Analysis by the think tank last year found that of the 13 CCS projects in operation globally, “failed or underperforming projects considerably outnumbered successful experiences”, while more recent research found that all have fallen short of an industry benchmark of 95% emissions captured.

Chevron’s Gorgon development, for example, has yet to deliver on targets agreed with local government to store around 4 million tonnes per year since its start up in 2019, and now expects to store less this year than last amid issues with water management and seismicity.

In contrast, CCS proponents argued IEEFA’s 2022 analysis was “too simplistic” and focused on under performance while not adequately considering why successful projects perform well.

Finally IEEFA also warned that project may “lock in” fossil fuel use for decades to come, with 81% of captured emissions from Track 1 projects set to come from processes that require fossil gas use.

IEEFA reports that “most of the support” for the schemes is being directed at oil and gas project owners, who account for an estimated 59% of total emissions during project startup, rising to 78% with further expansion.

“It is concerning that the UK government is being influenced in this way,” the report states.

“Previous analysis from IEEFA has highlighted the environmental and cost issues related to blue hydrogen production relative to green hydrogen, or using gas as opposed to renewable power.

“There are concerns about locking in long-term fossil gas demand when greener, cheaper alternatives with greater security of supply exist.”

© IEEFA

© IEEFA