© Supplied by SSE Thermal

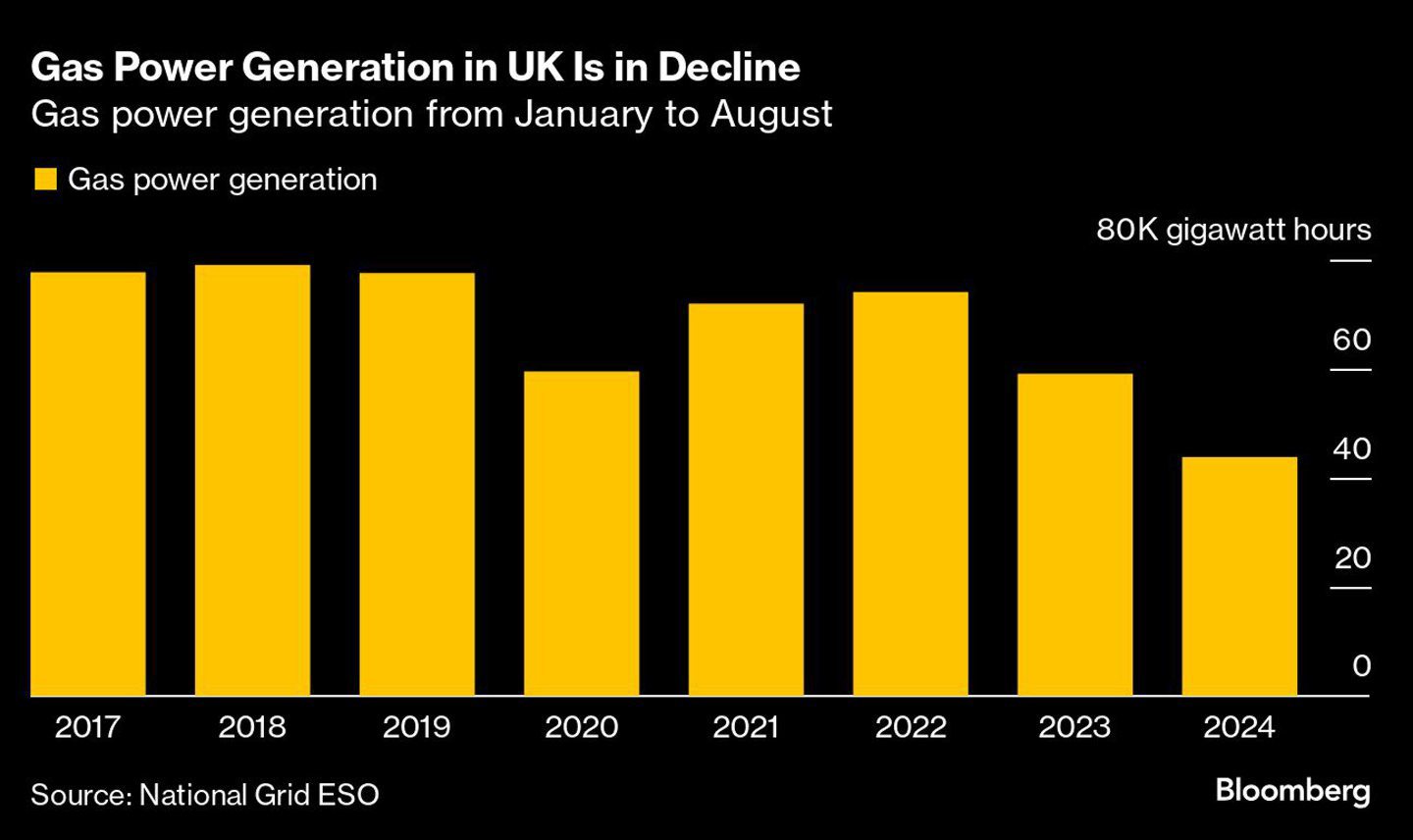

© Supplied by SSE Thermal UK gas-fired power plants are running at their lowest hours of operation since 2017 owing to high levels of wind, solar and imports from Norway and France into the national grid.

According to analysis by UK-based solar data company Kilowatts.io, less than half of combined cycle gas turbines (CCGTs) were online even during the most profitable hours in 2024.

Kilowatts.io developer Ben Watts said that, for over half the year, “only around 20% of CCGT capacity has been in operation”.

The amount of power generated by fossil fuels in the UK fell to its lowest level in over a century in August this year, as wind power capacity topped 30 GW for the first time.

Meanwhile, UK solar power capacity rose to just under 17 GW in July as electricity imports from six interconnector cables also soared to new highs.

France was the leading source of imported electricity to the UK grid, primarily from nuclear power, followed by mainly hydropower imports from Norway.

Altogether, this has led to a marked decline in gas-fired power generation in the UK.

But to ensure a stable supply of power when renewable output is low, gas plant owners across Europe continue to receive capacity payments to keep facilities operational even if they do not run.

This means that if CCGTs run for fewer hours during the year, they require more money from the UK government to stay profitable.

More gas-fired power?

But despite gas-fired power plants operating for fewer hours, the UK may still need to build new stations to decarbonise the electricity grid by 2030.

A report from the National Engineering Policy Centre found the UK will need additional baseload power, and new nuclear power plants will not be ready in time to meet the 2030 target.

The report referred to modelling suggesting that even in a highly decarbonised system, some unabated fossil capacity may be called upon during at least 25% of hours across the year in 2030 “even if only for a small proportion of total generation”.

Maintaining a strategic reserve of unabated gas capacity is “therefore a crucial aspect of ensuring security of supply”, the report said.

In March, the previous Conservative government set out plans to invest in unabated gas power into the 2030s maintain electricity supplies.

Similarly, Labour committed to maintain a “strategic reserve” of gas power stations in its election manifesto.

The North Sea offshore sector welcomed the move and said investment in gas power would protect UK jobs and reduce reliance on imports.

Energy analysts analysts also pointed to the electrification of home heating, which is set to increase winter power demand – requiring more peak generation.

But renewable energy advocates criticised the move, calling for more investment in long duration energy storage options such as batteries and pumped hydro to back up increased wind and solar output.

Hydrogen and CCS

In the event that the UK does invest in new CCGTs, efforts are underway to reduce their carbon intensity.

In December last year, the UK government announced it could support up to 20% hydrogen blending into the Great Britain gas network in “certain circumstances”.

EET Fuels is also aiming to become the first supplier of hydrogen-generated power to the UK grid by investing in a “hydrogen-ready” combined heat and power plant.

Meanwhile, the Scottish government is considering whether to approve a new gas-fired power plant at Peterhead with carbon capture and storage (CCS).