With some of the cheapest solar and wind costs in Asia Pacific, as well as virtually unlimited land resources, Australia has great potential to be a leading exporter of green hydrogen.

Australia’s extensive solar and wind resources leave it is well positioned to become a green hydrogen powerhouse. As a result, the country is leading the global pipeline for proposed low-carbon hydrogen projects.

Green hydrogen is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity generated by renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, thereby eliminating most of the emissions associated with legacy hydrogen production that uses fossil fuels.

The Australian government wants to ship green hydrogen to the world – building an export industry to gradually replace Australian shipments of natural gas and coal – as demand for fossil fuels is eventually expected to fall, as economies seek to decarbonise. Moreover, the country’s geographic proximity to major Asian energy demand markets, which keeps transportation costs relatively low, could see it become a significant exporter.

For starters, its National Hydrogen Strategy has set out plans for hydrogen hubs – clusters of large-scale demand and infrastructure to help foster the expansion of the industry. The government has also committed A$1 billion (US$690 million) for the development of clean hydrogen.

Therefore, it should come as no surprise that Australia leads the international pipeline for low-carbon hydrogen producing projects – making up 18% of proposed global developments, or 13 million tonnes per year of capacity, according to energy research firm Wood Mackenzie. Some 72% of the announced capacity is in Western Australia.

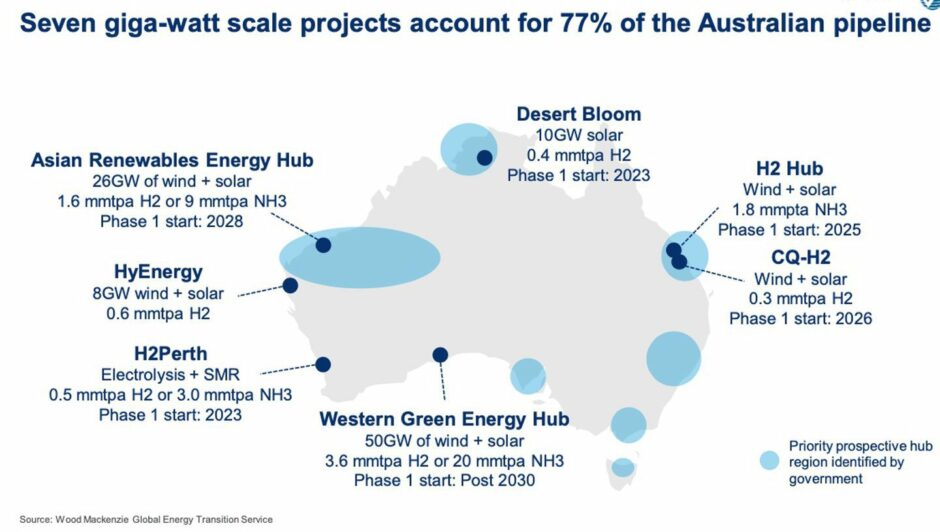

There are 90 proposed Australian projects, but the top seven gigawatt-scale developments account for 77% of the total in the country, Maria Yee, a senior analyst at the company, told Energy Voice. These projects are export orientated, targeting future demand centres – such as Japan and South Korea – that have aggressive decarbonisation targets.

However, infrastructure, demand, as well as technology, remain in the early stages of development. “There are quite a number of challenges, including permitting issues, availability of electrolysers, lack of serious offtake and difficulty securing finance,” added Yee.

Wood Mackenzie expects the early phases of the hydrogen projects to start-up from 2025, initially supplying the domestic market, but with some volumes for export. Significant production is projected post-2030.

Cost is key

All the projects have unique characteristics as they each try to find their own competitive edge. Among the big seven projects alone, they differ in size, export carrier, off-taker, business model, as well as end-technology, which makes the regulators jobs slightly more complicated.

The cost of green hydrogen is also a challenge. But the recent surge and volatility in global natural gas prices has pushed up the cost to produce hydrogen from gas, making the narrative for green hydrogen more compelling.

By 2030 a competitive price for green hydrogen at under US$2/kg is achievable in many markets, reckons Wood Mackenzie. However, low electricity prices and high utilisation rates will be crucial. Fortunately, Australia’s large-scale green hydrogen projects are expected to be cost competitive post 2030 given the country’s excellent natural wind and solar resource.

Midstream costs will also be important as transporting hydrogen is expensive and makes up a big portion of the delivered cost. Positively, Australia has lower delivery costs to Japan compared with other potential hydrogen exporters in the US and Middle East, due to its closer proximity.

Shipping hydrogen as ammonia or methanol, with the customer consuming it as ammonia or methanol – cutting out large reconversion costs – is more competitive than transporting liquid hydrogen. “On a pure economic basis, shipping ammonia and displacing ammonia usage at destination seems to make most sense, if it’s not cracked back into hydrogen. The big question is whether customers in Japan, South Korea, and elsewhere, are going to want to take ammonia and use ammonia,” said James Allan, director at Australia-based investment firm Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners.

Still, strong expected demand for hydrogen from Japan, South Korea, as well as Europe, could see it eventually become a tradable commodity. “I think people will be surprised how quickly it ramps up,” Allan told delegates at the recent Wood Mackenzie Power and Renewables Conference APAC.

“Within a year or two, we expect to see massive cost cuts in electrolysers and an explosion of final investment decisions. If this happens, then I would be surprised if we did not see some seaborne cargoes by the end of this decade and a decent initial market for seaborne hydrogen coming into view,” he added.

Indeed, Australia looks well positioned to become a major green hydrogen exporter with its excellent trade relationships in north Asia and globally. It is the only major net exporter of energy and commodities in Asia Pacific.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Wood Mackenzie

© Supplied by Wood Mackenzie