Australia’s Provaris (ASX:PV1) is looking to become a leader in the hydrogen midstream space, with eyes set on a fleet of vessels that would create Europe’s first supply lines for compressed green hydrogen.

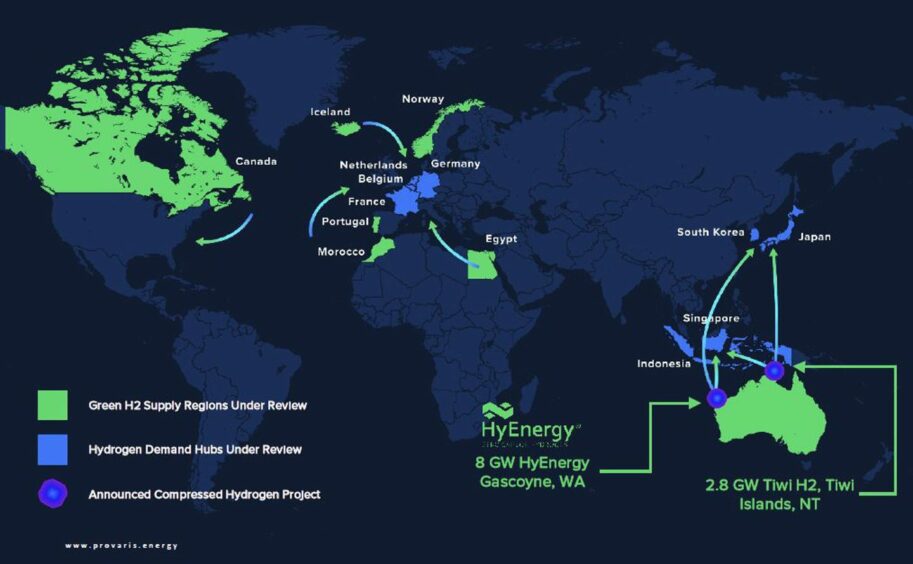

Headquartered in Perth, Australia, the group hopes to open up regional green hydrogen markets in Australia, East Asia and now Europe – with a compelling business case that eschews large-volume liquefaction or conversion in favour of smaller, cheaper and more efficient compression technology.

Formed in 2016 as Global Energy Ventures (GEV), the company was focused on developing a midstream business to deliver a commercial supply chain for compressed natural gas (CNG) in various regional export markets, using a brand-new class of vessel.

Its proposition was that compression technology allowed for export of gas at lower volumes and vastly reduced cost than that needed to make liquefied natural gas (LNG) economic.

Speaking with Energy Voice, managing director and chief executive Martin Carolan explained the rationale: “Compression was looked at as a low capital, cost-efficient way to move gas but it was limited in its regional distance. 500 to 1,000 nautical miles was its barrier and up to probably about 1 million tonnes of LNG equivalent,

“It was seen as niche to be fair, but there were some tremendous niche opportunities where you’re moving gas as an alternative to pipeline.”

However, the subsequent fall in gas prices and the move towards energy transition projects led the team to reposition its identity and its plans towards another fuel – clean hydrogen – which was equally well-suited to the business model.

Since that time Provaris has added a development team in Calgary and a new technical and commercial office in Oslo, in pursuit of several European work streams. It has also secured the backing of some of the world’s most influential energy majors, who also see the potential for regional hydrogen markets.

“2,000 nautical miles – and in the future with a larger vessel, 3,000 nautical miles – is kind of the extent,” noted Mr Carolan. “We can go much further, but really we are a regional play.”

GH2 carriers

Central to the proposition are the carriers themselves. Dubbed Gaseous Hydrogen (GH2), they are currently based on two design variants – H2Neo and H2Max – capable of carrying either 26,000m3 or 120,000m3 of compressed hydrogen (CH2), respectively.

They rely on hybrid electric propulsion, and are designed to run on LNG fuel (or potentially methanol), though Mr Carolan says future designs could also include hydrogen fuel cells.

Both designs received approval in principle in 2021, with the company now targeting approval for construction for its smaller variant by December this year.

Provaris’ model relies on a relatively simple value chain. Renewable energy feeds electricity into an electrolyser to produce hydrogen gas at 20 bar of pressure. This hydrogen is then compressed to 250 bar and loaded into the carriers using existing high-pressure gas loading arm systems, via a jetty.

Having sailed to its location, the ship then connects to another loading arm and offloads the compressed gas into a distribution pipeline, typically at 40-60 bar under its own pressure until it reaches equilibrium.

A small amount of decompression at the port facility then removes the remaining volumes.

“The key message here is its simplicity and its energy efficiency. We use less than 1 kWh per kilogramme to compress and load into the vessel, which then stored at ambient temperature – and it’s a closed system so there are no losses, no boil off,” he continued.

Moreover, the nature of compression means the ship can remain connected to the production facilities while hydrogen is being generated, acting as floating storage. Its flexibility also allows for production profiles to vary – unlike other solutions which require steady delivery of gas for stability.

Mr Carolan says the simpler, cheaper (but less energy-dense method) eschews much of the infrastructure and capital costs of other carrier solutions such as liquefied hydrogen or ammonia.

“What we’re trying to do is eliminate a lot of the capital intensive and energy intensive processes just to convert into a liquid or chemical, carry that in a vessel and then reconvert that back to gas,” he added.

“If your market end use is ammonia that’s fine – but where the majority of customers are looking for a molecule, that’s a gaseous product. We’re just moving the molecules from point, A to B in its existing form.”

If larger volumes are required, more vessels or larger vessels can simply be added to the floating pipeline to carry extra capacity, allowing producers and consumers to scale operations accordingly.

At 100,000-200,000 tonnes of CH2 per annum and up to 400,000 tonnes, he says the compressed option becomes “very competitive” against the alternatives, though at larger volumes other solutions are likely to become more attractive.

Global aspirations

Nevertheless, the demand and distances required in Europe make CH2 an attractive option.

Mr Carolan said the group is now pursuing “a number of opportunities” to ship supplies into Germany and the Netherlands, focused largely around the former’s plans for a so-called hydrogen backbone of infrastructure and industrial consumers.

Provaris intends to use its vessels to link these ports with producers from Norway as well as Spain, Portugal and Morocco, over distances of 400-1,000 miles.

He also pointed to the Shetland Islands, where the prospect of monetising excess renewable energy has long been a goal for local developers.

“It’s a well known area for renewable power, there’s onshore and offshore wind being developed there, so we’re working with one of the groups there who are looking to – rather than curtail and spill renewable power in their cycle – they’re looking to capture that and monetize that renewable energy in the form of hydrogen.”

“And again, that’s 300 to 400 nautical miles, so less than two days sailing across to the key ports there in Europe.”

“They are all investment-grade bankable groups that are looking to either produce hydrogen as a as an add on to their existing renewable facilities or they are building brand new renewable hydrogen integrated projects.”

A port facility into the backbone is expected be ready by 2026-27. Provaris, meanwhile intends to be ready with its vessels to meet that deadline, while producers will bring facilities online between 2026-28.

Carolan says the commercial model is likely to be a long-term take or pay contract, for which the company will deliver the shipping fleet and compression requirements – as well as port infrastructure if required.

Other potential projects to be explored include linking the carrier vessels directly to electrolysers at offshore wind farms, again avoiding the need for storage.

Meanwhile, in Australia the company is also taking on the role of developer for the TiwiH2 project, which would see a 2.8GW solar farm provide up to 100,000 tonnes of CH2 per year, for delivery to clients in Japan, Singapore and South Korea.

Ultimately, Mr Carolan is emphatic on the value he says the company can deliver – in applications that no longer seem niche.

“What the market is telling us – and it’s evidenced by Total EREN, if you look at their announcements, they are only announcing ammonia projects – what they’re saying to us is that if your delivered cost for volume is better than the cost of delivered NH3 without the complexity of adding all that capital, then that’s a game changer.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Provaris

© Supplied by Provaris © Supplied by Provaris

© Supplied by Provaris