The tree-lined street in Leipzig may seem an incongruous beachhead for the future of German energy. But the government has billions riding on its success.

Today, the bright yellow power plant tucked behind a graffiti-covered fence burns planet-warming gas to produce electricity. But if all goes to plan, it will one day switch to emissions-free hydrogen. It’s the first, tiny part of a dream energy system being sketched out by policymakers across Europe, who are banking on the green fuel to meet some of the world’s most aggressive climate targets. That dream rests on converting newly built polluting infrastructure to burn hydrogen, a fuel that’ll be many times more expensive than natural gas and that no one has figured out how to move safely and cheaply in bulk.

Experts agree that hydrogen will have to play some role in getting the world to net-zero in sectors such as steelmaking, aviation and shipping. The handful of early projects focused on using hydrogen to generate power in Europe, however, show that it won’t be as easy a swap as advocates make it out to be.

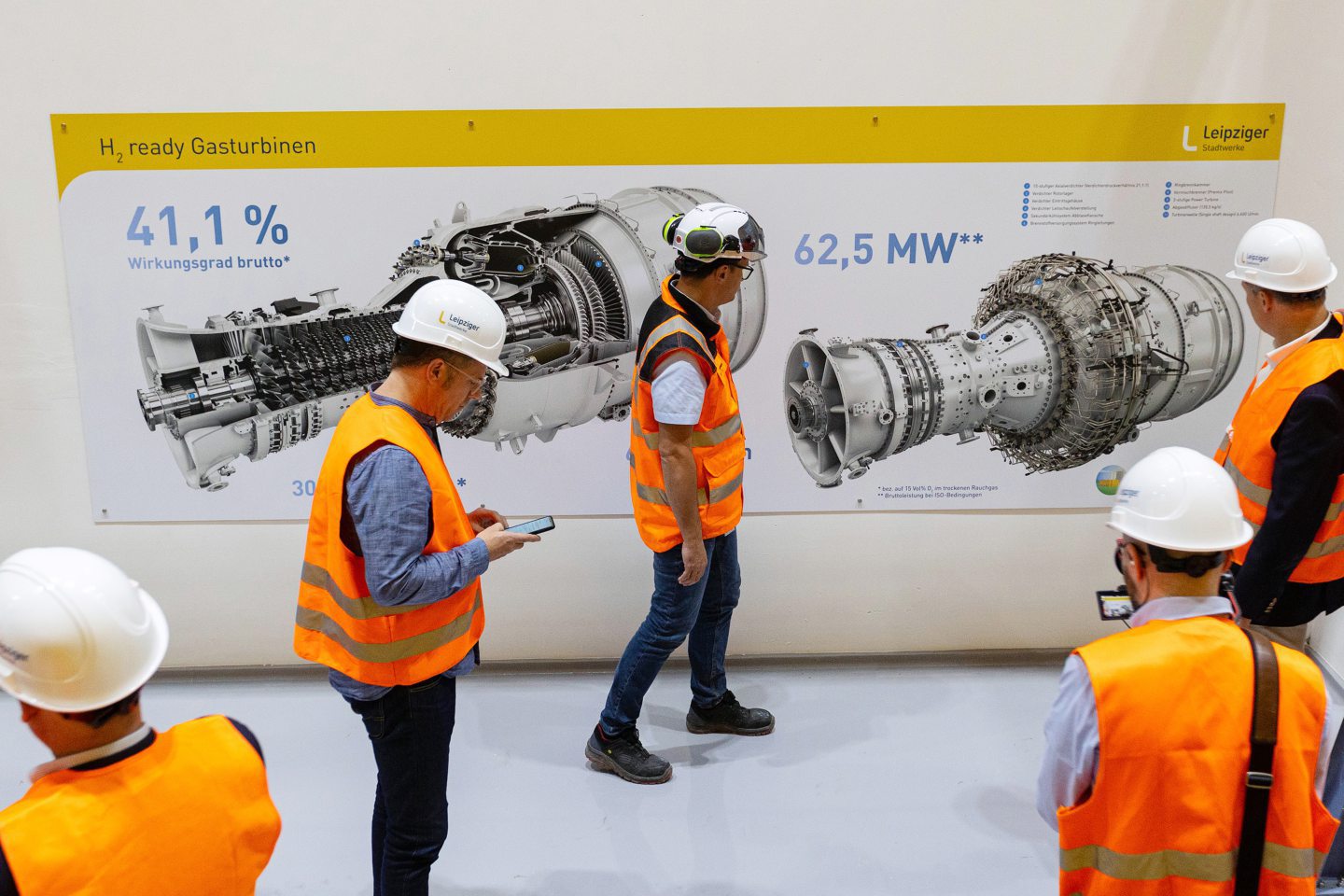

The Leipzig power plant was inaugurated in October. It was built in just two years, despite pandemic-induced supply chain hurdles, and workers were still applying shiny blue paint to the railings in April. A sheet steel and plastic case houses two Siemens Energy turbines that are supposed to be able to combust 100% hydrogen gas with just a few tweaks.

Leipziger Stadtwerke, the local utility running the project, aims to do its first commercial tests with hydrogen by 2026, according to Christoph Jansen, the company’s head of generation. It could be a “gamechanger,” he said, for a town that still largely relies on mining lignite, a particularly dirty type of coal.

Germany plans to build more than 20 power plants much bigger than the one in Leipzig, which it advertises as the continent’s first “hydrogen-ready” facility. They’ll be supplied by state-of-the-art liquefied natural gas terminals equipped to handle niche clean fuels such as ammonia, and a network of special pipes stretching roughly 6,000 miles (9,600 kilometers).

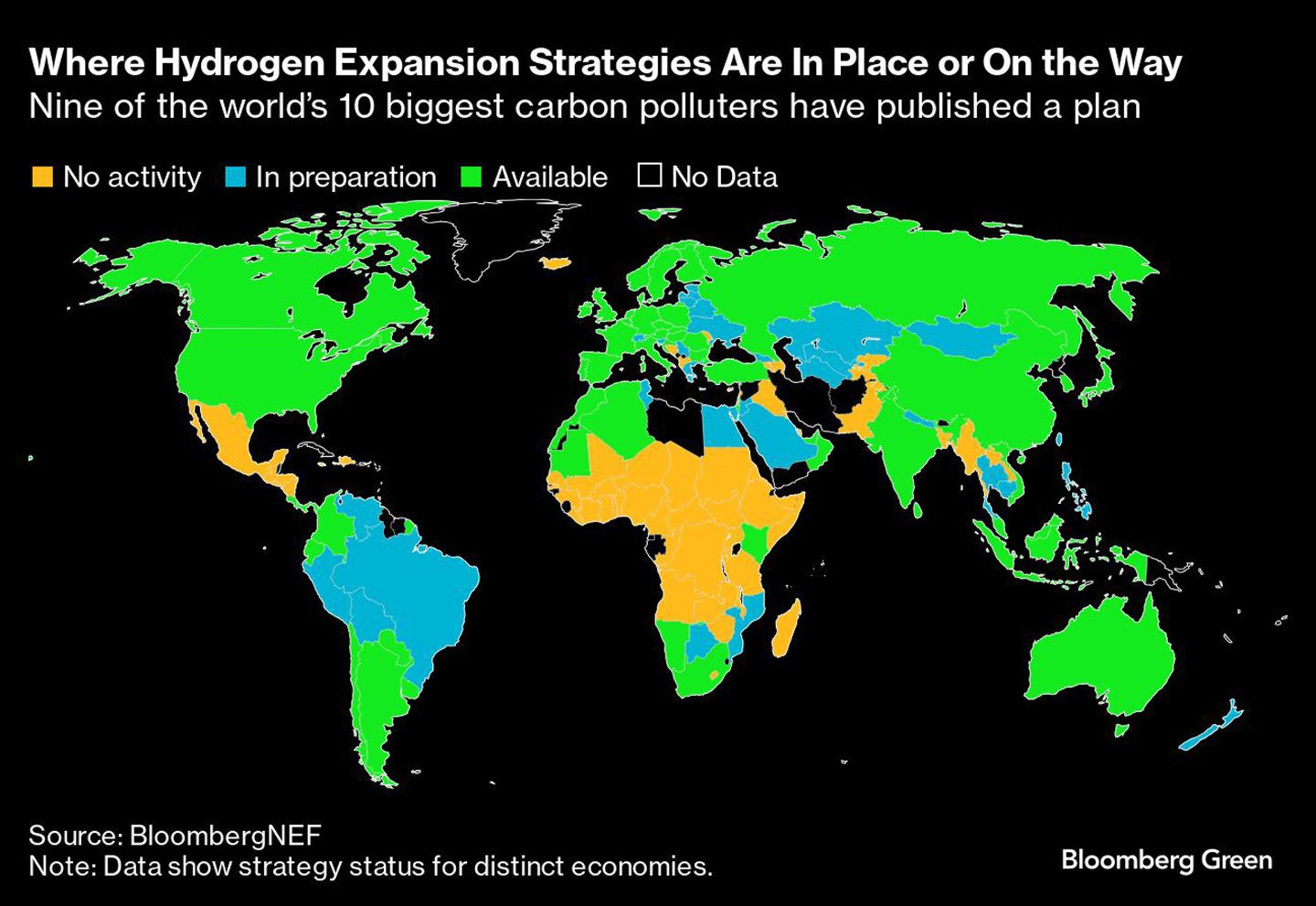

It’s a tempting solution. Following this model, governments and companies that are racing to meet net-zero deadlines but worried about energy security can still build billions of dollars worth of gas infrastructure as long as it’s “hydrogen-ready.” Nine of the world’s 10 biggest carbon polluters have published hydrogen strategies and incentives to grow the fuel’s use globally already exceed $360 billion, according to BloombergNEF.

Gas-dependent economies including Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy and the UK are among Europe’s biggest proponents for using hydrogen and some have plans to use it to generate electricity. But there’s no official definition of what makes a plant hydrogen-ready, opening the door for greenwashing. For power plants, burning hydrogen hasn’t even been tested at scale.

“There has not yet been any measurable progress in the construction of hydrogen-ready, gas-fired power plants,” said Eric Heymann, an economist at Deutsche Bank Research.

Then there’s the problem of moving hydrogen around. The Leipzig plant isn’t hooked up to the grid (and hasn’t yet set up own electrolyzers), which means the highly combustible fuel will have to be trucked in until the second part of the government’s grand plan comes to fruition. It’s building a €1 billion liquefied natural gas terminal in Brunsbuettel, a town along the North Sea, that will initially import LNG but be designed to also handle futuristic clean fuels.

Hydrogen can only be liquefied at -253C (-423F), well beyond the capabilities of today’s LNG ships. So Germany is planning to import hydrogen in the form of liquid ammonia, a combination of hydrogen and nitrogen that can more easily be turned into a liquid. But ammonia is toxic and handling requires better ventilation systems. Many components in the terminal, including control valves and fire and gas sensors as well as inline devices — most of which have not been tested with ammonia — will also need upgrades, according to Fraunhofer ISI, an energy think tank.

Germany doesn’t have an ammonia pipeline network and there are limitations to moving it via trucks on an industrial scale because it’s hazardous. That means ammonia will have to be converted back into hydrogen, yet there’s no economically viable technology currently available to do that. The terminal’s operator said it will discuss alternative strategies if none emerge by next year.

“The German government is making a risky bet here,” said Jonathan Barth, spokesperson of the German Energy Independence Council. “Hydrogen should be limited to no-regret applications,” he said. “Hoping that all problems can be solved with hydrogen prevents us from starting now where we can.”

Industries can be built from the ground up with enough support. The renewable energy industry was in its infancy 20 years ago and faced skepticism. Now it’s booming.

The difference is that wind and solar produce clean electricity — a commodity the world already uses. Green hydrogen, on the other hand, will require building more solar and wind farms when, in many cases, it would be simpler to just use that clean energy directly. By the time hydrogen is made, stored and burned to make electricity again, there’s nearly 70% less energy than at the start — and the cost has tripled.

Green hydrogen will probably only be useful towards the end of the energy transition, once primary electricity demand is being comfortably met by renewables, according to Pierre Wunsch, Belgium’s top central banker. “We’re not going to have green hydrogen in big quantities and cheap prices before that because of course we need to produce more electricity to electrify,” he said.

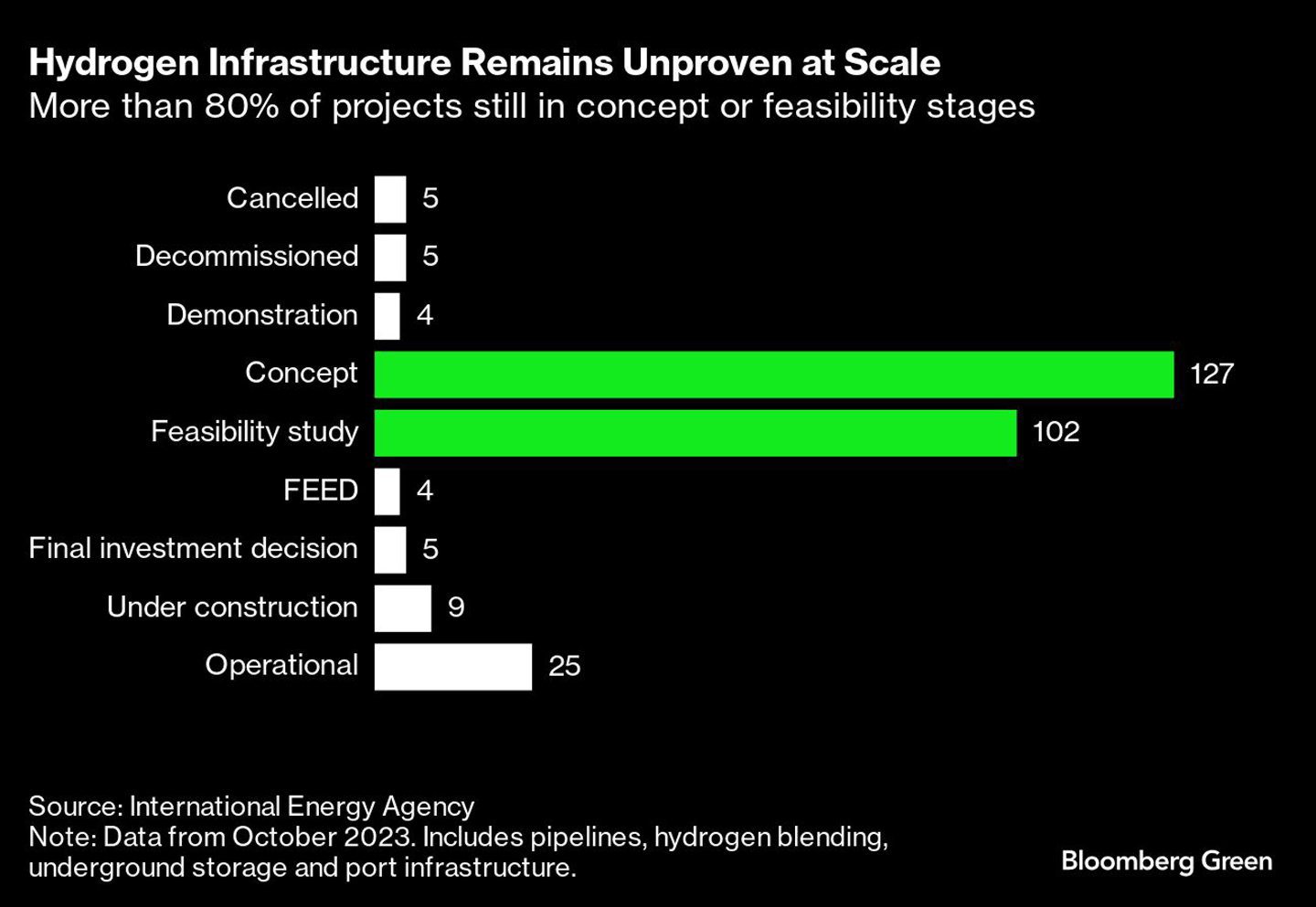

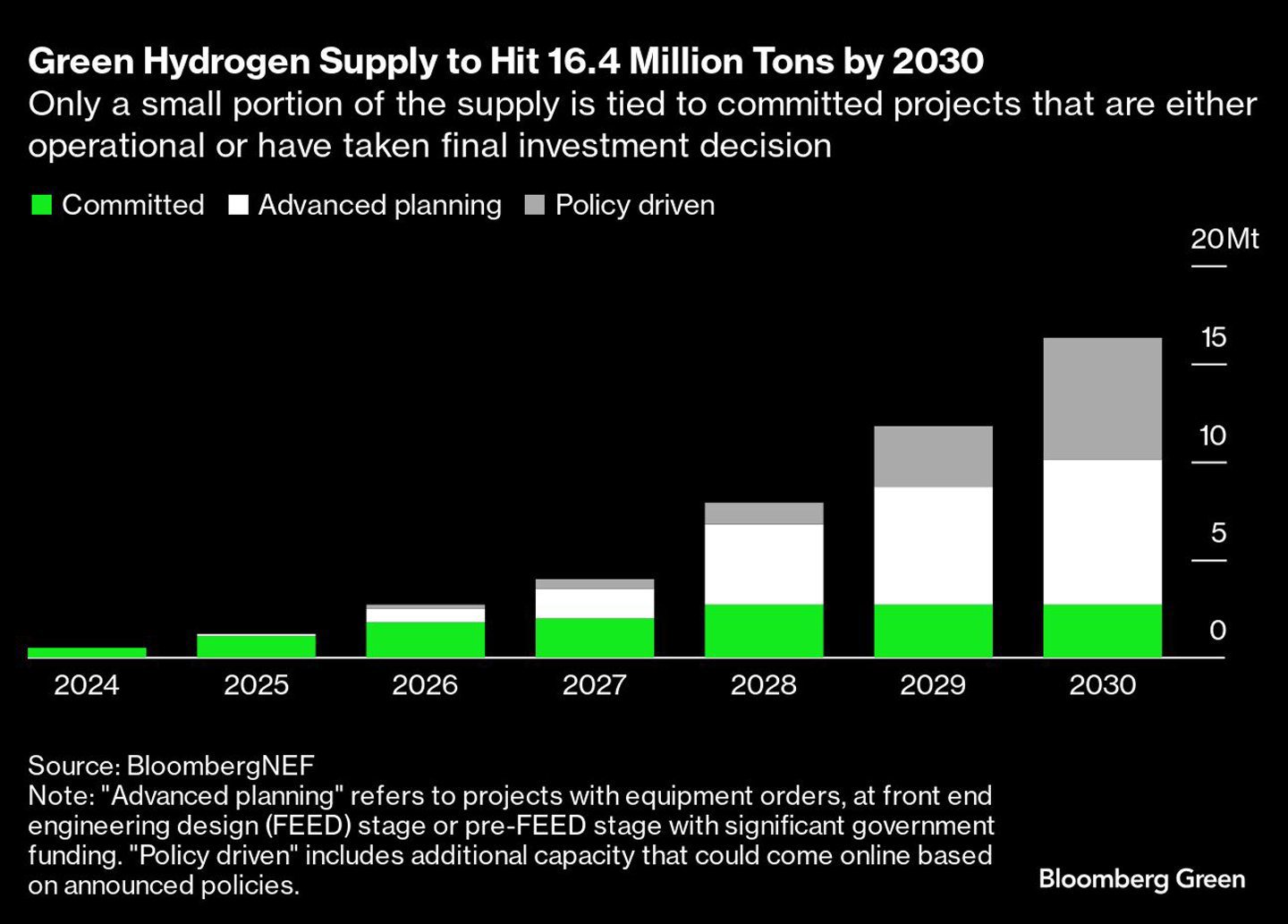

That’s perhaps why most green hydrogen projects only exist on paper or the websites of major gas companies like Equinor ASA, Shell Plc and Sinopec. A chasm is emerging between the scale of the political ambition and the money on the table from companies to build the projects; just 4% of proposed global projects reached financial close in 2023, according to the International Energy Agency. Others are already falling through the gap.

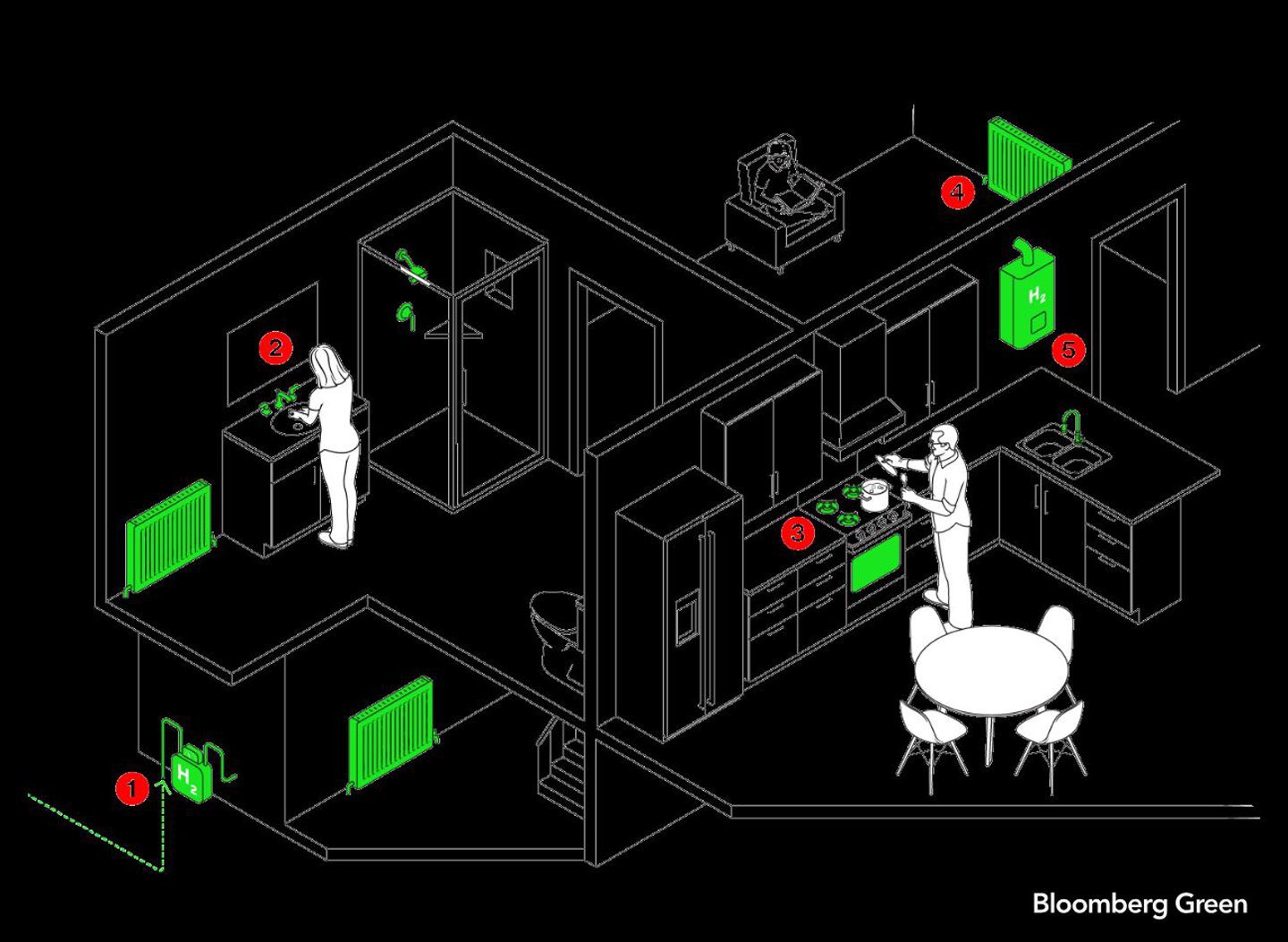

Redcar, a tiny seaside village in the UK known for its long sandy beach and lemon sorbet-topped ice cream cones, was slated to be the site of a hydrogen home heating and cooking pilot last year.

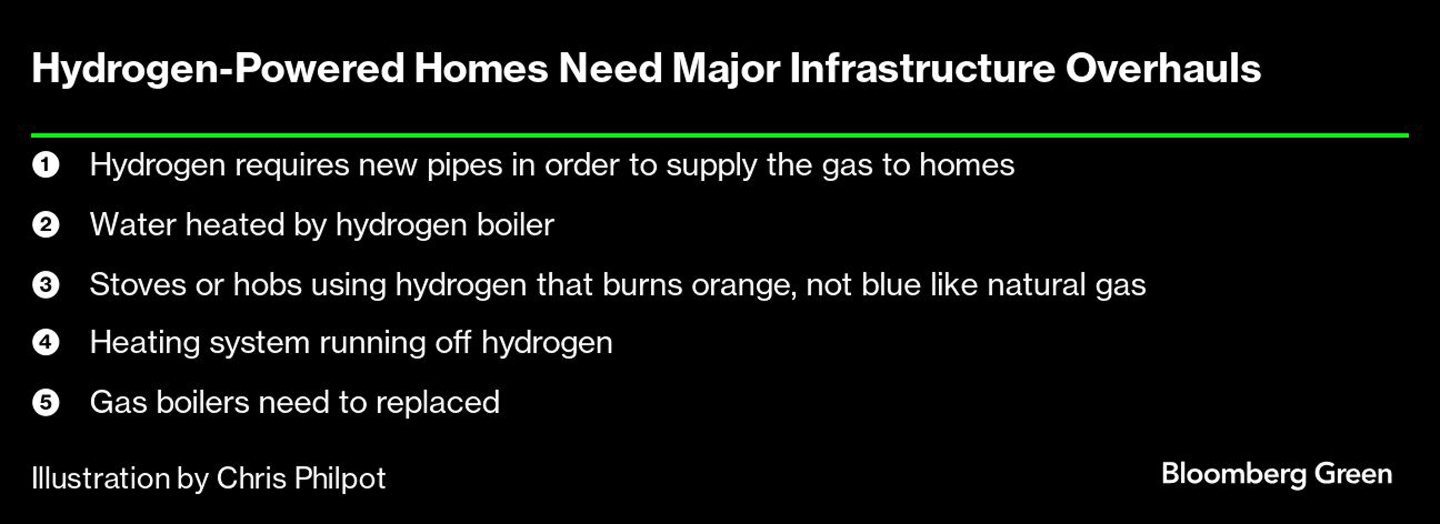

Northern Gas Networks Ltd. pitched it as an easy way to lower energy bills and carbon footprints. It turned out the project would be mandatory, requiring everyone to give up gas and switch to a hydrogen grid. The switch would also result in major, disruptive renovations including a separate set of pipelines and new home furnaces and stoves.

Multiple residents told Bloomberg Green there was no information about how much hydrogen would be available after the trial ended or how much it would cost. After a wave of local protests, the government canceled the project due to a lack of green hydrogen.

“We were open, transparent and honest,” said Tim Harwood, who runs the hydrogen program at Northern Gas Networks. “Everything we were going to do was in the best interest of customers.”

That’s not how everyone perceived it. Northern Gas was “selling a lie,” said Steve Rudd, who asked his tenants to leave the house he owns in Redcar because he didn’t want the liability of having them be guinea pigs.

“Hydrogen has been known about for years and it’s not been used,” Rudd said. “It’s energy intensive and it costs more.”

A January review of 54 studies concluded that hydrogen will at best play a niche role in decarbonizing buildings because it’s less efficient and more expensive than heat pumps, district heating and better insulation. That hasn’t stopped other companies from trying to make it work: There’s a home heating trial underway in the Netherlands and another planned in Scotland.

Jan Rosenow, Europe director at the European Regulatory Assistance Project who authored the review, worries the bid to replace gas in buildings with hydrogen is becoming a costly distraction. “There’s a risk the discussion on hydrogen for heating will lead to a delay in the introduction of alternative cheaper and cleaner heating technologies,” he said.

Hydrogen evangelists readily admit it’s possible the world will never produce the green fuel at a low enough price to replace gas. But they’re still advocating for the construction of “hydrogen-ready” gas infrastructure in the hope that the market catches up.

It’s a big gamble. If they’re wrong, the world risks locking in decades of fossil fuel pollution and blowing past targets for cutting emissions. Doing so will result in catastrophic climate impacts.

Germany, for example, plans to set aside up to €20 billion to make it economically viable for utilities to transition to hydrogen, as the country will urgently need backup for times when sun and wind are not available amid soaring power demand. If those subsidies don’t come through, “there is a risk that power plants will simply continue to run on natural gas,” said Claudia Günther, research lead for Germany at think tank Aurora Energy Research.

Despite already scrapping three hydrogen projects, German utility Uniper SE is preparing to build a new fleet of “hydrogen-ready” gas plants. Chief Executive Officer Michael Lewis says it’s a chicken-and-egg situation. “Today, of course, it’s expensive because there’s no infrastructure for hydrogen in place yet and there’s no economies of scale,” he said. Yet with no real chicken or egg to speak of yet, he said at the company’s annual general meeting this month that “in just over six years, our portfolio will change from grey to green.”

Robert Habeck, Germany’s economy and climate action minister and Green Party member, says his country has already scaled back its hydrogen plans and is clear-eyed about the challenges.

“Germany needs a lot of hydrogen to help its fossil-fuel-heavy industry on its way towards climate neutrality,’’ he said. “We had to adapt our initial plan of using hydrogen in power plants on a large scale because we had to save costs.”

It’s a “make or break” year for hydrogen, according to an S&P Global report published last December. The industry is encountering cost increases, with required capital expenditure estimates going up by 40% to 50%. To make headway, companies will need to make 10 to 15 large final investment decisions. The odds of that happening, at least in Europe, could be steep ones.

“The math still doesn’t add up,” said Jean-Christophe Laloux, head of EU lending and advisory operations at the European Investment Bank. “At the moment, there is no case that we can see for a model based on green hydrogen independently produced and distributed as an energy commodity.”

© Photographer: Krisztian Bocsi/Bl

© Photographer: Krisztian Bocsi/Bl © Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg © Photographer: Krisztian Bocsi/Bloomberg

© Photographer: Krisztian Bocsi/Bloomberg © Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg © Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg © Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg © FELIPE TRUEBA/EPA-EFE/Shuttersto

© FELIPE TRUEBA/EPA-EFE/Shuttersto