Germany’s freshly-approved strategy to import hydrogen has been criticized by industry groups for ignoring the lack of credible pipelines to bring supplies of the clean gas from other parts of Europe.

Last week, the European Union’s spending watchdog warned that the region’s green hydrogen ambitions are being driven by political will rather than robust analysis. Germany has one of the most wide-spanning plans in its mission to replace coal — first with natural gas to cut emissions quickly and then with hydrogen. There are serious questions about whether hydrogen will be available at the scale Germany needs and at an affordable cost.

Germany says it will be one of the world’s largest hydrogen buyers, and will import supplies from Europe and Africa. The government is hoping that this declaration will be enough to incentivize companies to finance hydrogen production as well as pipeline projects like the H2Med that connect to Spain.

The import strategy will “help to ensure investment security for hydrogen production in partner countries and the development of the necessary import infrastructure,” according to the strategy paper approved by the cabinet on Wednesday.

The need is clear. Europe’s biggest economy will need imports to cover about 70% of its demand of up to 130 terawatt-hours by 2030, according to the strategy paper.

But estimates aren’t enough for investors to put down their cash.

The strategy “gives no indication of a reliable increase in demand in Germany,” Timm Kehler, head of gas group Zukunft Gas, said in a statement. “The international suppliers of hydrogen are waiting for clear signals and impetus to trigger investment in capital-intensive hydrogen production.”

Plan Needed

The economy ministry lists a variety of financing tools — such as global auctions, a row of subsidies, 15-year contracts with energy-intensive industries, or awards by the European Hydrogen Bank. What’s missing is a detailed plan for how the hydrogen will get to Germany.

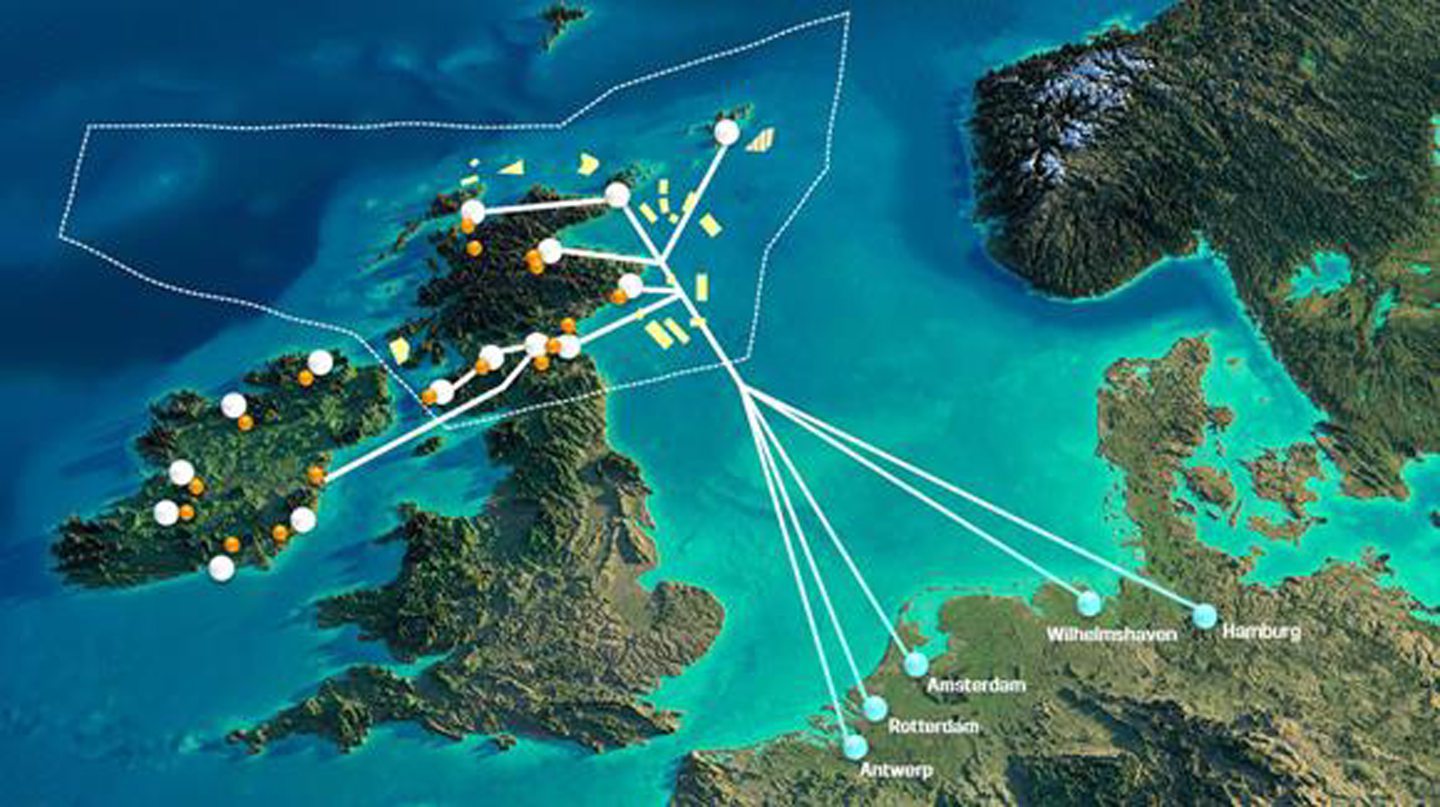

Germany will initially rely mainly on piped supplies from its direct neighbors in the Baltic or North Sea — such as Norway, Denmark or the UK — but it is also preparing infrastructure for shipped ammonia.

This week, the nation’s grid operators submitted planning approval for a €20 billion ($21.7 billion) hydrogen network. However there are no agreements to connect to the European network, according to Frank Peter, head of think tank Agora Industry.

While industry groups in principle welcomed the strategy, the German Steel Federation also called for “sufficient financing of import instruments.”

Germany’s steelmakers will be particularly dependent on hydrogen imports to clean up their emissions-heavy business. For example, Thyssenkrupp AG, which was responsible for almost 3% of all German CO2 emissions last year, said that its first direct reduction plant will require about 400 tons of the clean gas each day.

Other countries lack Germany’s drive to develop hydrogen infrastructure, said Yvonne Ruf, partner at consultancy Roland Berger.

“The fundamental question of how the price of hydrogen and thus also the demand will develop is still causing a great deal of hesitation and reluctance to invest worldwide,” Ruf said.

© Supplied by NZTC

© Supplied by NZTC © Bloomberg

© Bloomberg