The most popular decarbonisation solutions will be those that require little or no behavioural change and do not cost the earth. Humans are creatures of habit and, perhaps more importantly, comfort.

When it comes to slashing emissions arising from the heating of homes and buildings, that gives hydrogen blending a significant leg up.

There is an aspiration to inject low carbon hydrogen into the existing network, alongside conventional fuel at first, where it can be used for cooking food, heating water and keeping people cosy on cold winter nights.

“There’s a lot of work going on at the moment to look at how to convert and repurpose the gas transmission and redistribution system for a blend of hydrogen in natural gas, and latterly 100% hydrogen,” John Aldersey-Williams, associate at Progressive Energy, told the Southern North Sea conference recently.

“In fact there have been trials already to see what happens if you put a 20% blend of hydrogen into natural gas in the domestic supply, and the answer is nobody notices. It appears to be perfectly feasible and perfectly safe to blend hydrogen into natural gas, subject to the regulatory constraints.”

The vast majority (85%) of homes and businesses in the UK currently rely on natural gas, and incorporating up to 20% hydrogen into the mix save around 6 million tonnes of CO2 a year, according to the Energy Networks Association (ENA).

In its flagship Ten Point Plan, UK Government pledged to work with industry to help facilitate that target by 2023.

A number of hurdles still have to be cleared though. A damning report recently published by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) described hydrogen blending as an “expensive and ineffective” way to reduce emissions.

On a practical level, hydrogen production in the UK needs to be ramped up drastically, and regulators need to ensure networks and buildings are ship shape.

When and if that is achieved, it will create a pathway from production to end use, helping to scale up the UK’s hydrogen network and potentially delivering large emissions reductions.

Energy and climate change minister Greg Hands has held hydrogen up as the UK’s “new super-fuel” that can be produced domestically using “our skills, experience and natural resources”.

He added: “As announced in our British Energy Security Strategy, we are doubling our hydrogen ambition to up to 10GW of low carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030.

“This builds on our Hydrogen Strategy, published last year, which outlines a comprehensive roadmap to make the UK a world-leading hydrogen economy, set to support over 9,000 UK jobs and unlock £4 billion investment by 2030.”

Upstream

First, before any hydrogen blending plans can be put into place, a stable supply of the fuel is required.

Countless projects up and down the UK are at various stages of readiness, aiming to produce low carbon hydrogen in its two dominant forms; blue – derived from natural gas with carbon capture used to nullify emissions – and green – produced using clean electricity and water.

Just off the coast of Aberdeen, Vattenfall is exploring using its European Offshore Wind Deployment Centre (EOWDC) to create the fuel.

Dubbed Hydrogen Turbine 1 (HT1), the proposals involve installing hydrogen generating equipment – an electrolyser, desalination facilities and compressors – on a platform at one of the development’s 11 turbines.

In doing so the Swedish renewables giant is aiming to demonstrate the feasibility of offshore hydrogen production, a key component in making the most of green energy generation.

Danielle Lane, head of asset value and partnering at Vattenfall, said: “We as a company are very proud that we’ve got some funding from the government for a full-scale, world first demonstration of a hydrogen turbine within an offshore wind farm.

“This will take place at our EOWDC in Aberdeen bay, the wind farm that Donald Trump really didn’t want but is now happily in operation.

“It has already been a testbed for many different types of innovations in the wind industry, and now we’re going to see an 8 megawatt (MW) turbine converted to produce hydrogen. The electrolyser will be co-located offshore, and we intend for it to commence operation in 2025.

“This is the first step on a journey to being able to produce, large-scale green hydrogen from offshore wind turbines and we’re really excited about it.”

Meanwhile Environmental Resources Management (ERM) has also previously signalled its intent to situate its Dolphyn green hydrogen project off Aberdeen.

And with hundreds of turbines due to spring up in Scottish waters in the coming years, hydrogen could soon be being produced offshore around the clock.

On the onshore side of things, hydrogen initiatives are central to the several decarbonisation clusters that have taken shape around the UK.

The Acorn carbon capture and storage (CCS) project – the backbone of the Scottish cluster – is looking at producing blue hydrogen at the St Fergus gas terminal and sending the emissions to depleted reservoirs under the North Sea.

More than 100 miles south, petrochemicals giant Ineos is pushing on with plans for a hydrogen production plant at Grangemouth that could bring down emissions by 60%.

Carbon dioxide produced by the facility would be captured and sent to the north-east to be dealt with by Acorn.

Similar tales are playing out across the UK as businesses and initiatives club together to try to secure first mover advantage.

Midstream

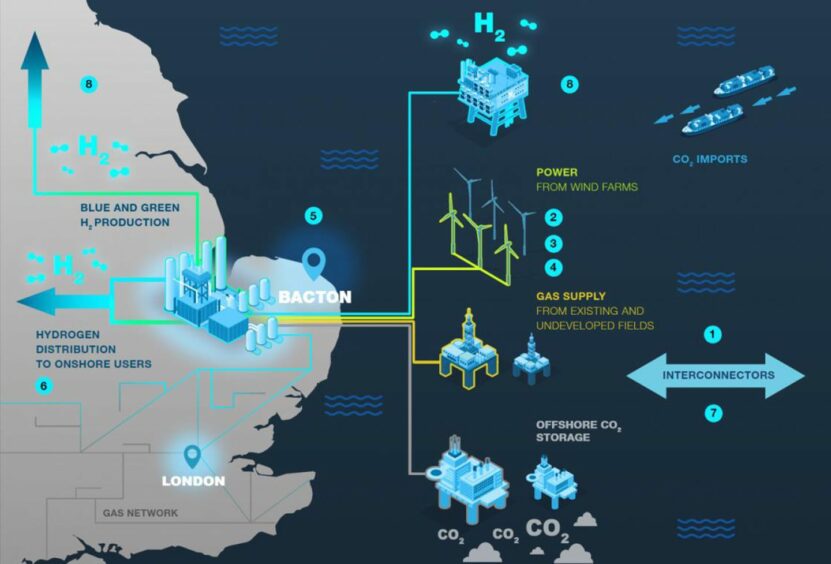

The Bacton Gas Terminal in Norfolk has been held up as a site of “national importance” by Martin Dronfield, executive chairman of the East of England Energy Group (EEEG).

Currently the facility receives around a third of the UK’s natural gas, but work is well underway to revamp the site for the energy transition.

Under plans laid out by the North Sea Transition Authority, the Bacton Energy Hub will become a hotbed for hydrogen production and distribution in the 2030s.

Natural gas from the Southern North Sea will be transformed at the facility into the low carbon fuel, with emissions going the other way.

From there, existing infrastructure can be used to pipe hydrogen into homes and businesses around England, including London and the Midlands.

A host of companies are working on the scheme including energy services firm Petrofac, consultancy Xodus, and engineering giant McDermott International.

Daniel Paterson, lead consultant at Xodus, said: “We are proud to be leading the infrastructure special interestgroups (SIG) for the Bacton Energy Hub as we see this as a nationally significant project which can help support a low carbon economy and create jobs for local people.

“Infrastructure will play a key role in enabling hydrogen production and being part of this project is an exciting chance for us to contribute to delivering a responsible energy future for the UK.”

Downstream

There just remains the small matter of blending hydrogen into the gas grid, with the ultimate aim of the superfuel becoming a standalone in the decades to come.

While the concept may sound pretty simple, the ENA says “a lot of work” still need to be done “behind the scenes to get hydrogen blending and production off the ground”.

A spokesman for the organisation said: “Whilst technical trials have been progressing, the regulators need to also focus on the non-technical aspects to ensure that networks are ready and able to accept hydrogen as soon as production is available.”

They added: “At the moment, only 0.1% of the gas in Britain’s network of gas pipelines is allowed to be hydrogen, by law. The time is now right to start looking at how we change that law so that a 20% blend is allowed.

“Once innovation and safety trials have progressed to the next stage, that will allow gas networks to start blending far larger amounts of hydrogen into the grid – creating the demand for hydrogen that will help get the industry required to produce it off to a flying start.”

Of course, the deployment of hydrogen into residential areas throws up a number of potential safety issues.

As Matt Damon quipped in Ridley Scott’s 2015 film The Martian, “luckily, in the history of humanity, nothing bad has ever happened from lighting hydrogen on fire”.

The ENA says it is taking a “safety-first approach” to hydrogen blending and is working with the likes of the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) to minimise risk.

Work on experimental hydrogen projects is also carried out in a “controlled off-grid environment” before moving on to “limited trials” in public settings.

And initial schemes are already showing that “using our gas networks to deliver hydrogen is fundamentally safe, for households to use for their heating, hot water and cooking”.

A spokesman for the ENA added: “We need to reduce the carbon emissions from Britain’s homes, to play our part in stopping climate change. The best way to do that is to take a balanced approach and giving customers choice is the best, least disruptive and most affordable way to decarbonise how we heat, live and work in our homes and businesses.”

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Supplied by DCT Media/ Wullie Ma

© Supplied by DCT Media/ Wullie Ma © Supplied by Scottish Power

© Supplied by Scottish Power © Supplied by Ineos

© Supplied by Ineos © Supplied by Big Partnership

© Supplied by Big Partnership © Supplied by Big Partnership

© Supplied by Big Partnership © Shutterstock / petrmalinak

© Shutterstock / petrmalinak