New analysis suggests the UK’s hydrogen targets may fall short of what is needed to decarbonise the power sector, while the supply gap could impact other industry plans to slash emissions.

Analysis by the Climate Change Committee (CCC) suggests that current targets for hydrogen production capacity are “on the lower end of what could be needed” to decarbonise the power sector by 2035.

With supplies tight, the committee chief executive Chris Stark said many sectors risked “wishful thinking” on having access to abundant flows of the green fuel.

Alongside the UK’s goal for a net-zero economy by 2050, the British Energy Security Strategy (BESS) calls for a fully decarbonised electricity system by 2035, underpinned by a massive expansion of nuclear, offshore wind and hydrogen capacity.

The UK has already doubled its near-term ambitions to build up to 10GW of low-carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030, at least half of which should come from renewably powered electrolytic or “green” hydrogen.

In combination with “blue” hydrogen – derived from fossil gas with captured emissions – this would be used to help decarbonise power, transport, heat and other sectors.

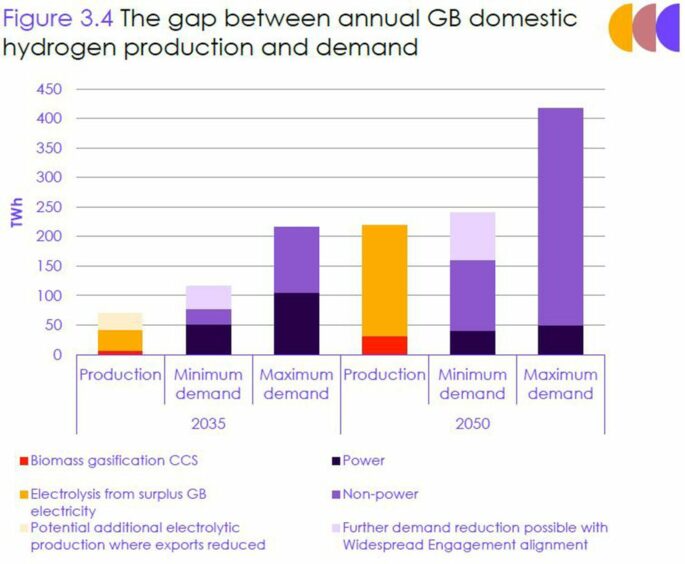

Yet the CCC estimates that production capacity from these current targets represents around 22-62 TWh annually, while demand from the power sector alone could be around 85 TWh in 2035.

Explaining the findings, Mr Stark said: “We think the government’s targets for hydrogen generation are probably on the low side.

“We also need storage for hydrogen, but one of the other aspects of this report is it starts to ask some pretty probing questions about the extent to which hydrogen can be used in other sectors at any great scale.”

Green supplies ‘unlikely’ to meet demand

Accordingly, the report finds it “unlikely” that all hydrogen demand in 2035 can be met from green domestic production.

Depending on how much electricity is exported and how much hydrogen is consumed outside the power sector, the analysis suggests an overall supply gap between hydrogen production from non-fossil sources and demand could be in the anywhere from 7-174 TWh in 2035.

That gap could be somewhat filled by domestic blue hydrogen, but it would also require a rise in imported gas to make the decarbonised fuel and additional CCS requirements.

“You can see the challenge by 2035 that we are not going to have as much green hydrogen production as many out there seem to think we will have,” Mr Stark added.

“It’s possible that we’ll be able to do more, but meeting the gaps to some of these very high demand scenarios for hydrogen – in particular hydrogen boilers, buildings – that becomes very difficult.

Energy security risks

He also acknowledged that increasing imports of gas – or even ready-made green hydrogen – could represent “a potential new energy security risk”.

For that reason, Mr Stark said the findings suggested sectors which could look to other means of decarbonising – such as buildings and heating – may be better off opting for electrification over hydrogen.

“Although those scenarios are possible in theory, I really feel we should be pushing towards the scenarios that have lower hydrogen demand as a means to deliver an extra level of energy security,” he explained.

“By 2050 the position may have changed again, but over the next 15 years or so things are pretty tight.

“There’s a bit of wishful thinking going on out there. Many of the sectors that think they’ll have free and unconstrained access to that hydrogen in the 2030s and beyond – that’s not the case, so we’ve got to make careful decisions about that.”

The government published a Hydrogen Strategy in 2021 and an Investor Roadmap for the technology last year. Most recently in December it published heads of terms for a hydrogen business model.

Yet a decision on whether to back hydrogen for home heating, for example, is not due until 2026.

However, Mr Stark and his colleagues said the pace of development for these technologies was not currently quick enough to meet 2035 goals, and suggested the administration take “more of a designing hand” in setting expectations from hydrogen.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Climate Change Commi

© Supplied by Climate Change Commi