As interest and investment in nuclear energy increases around the world, will Scotland’s longstanding opposition to the technology see it miss out on an economic boost?

Nuclear energy is having a moment as major tech firms and governments around the world look to invest in the promise of cheaper, smaller and more efficient facilities.

The UK government is in the process of selecting the winners of its £20 billion small modular reactor (SMR) competition.

Elsewhere, China and the United States are investing heavily in research and development, targeting advanced modular reactors (AMRs), microreactors, and the holy grail of nuclear energy: fusion.

The UK government is also pressing ahead with a £20 billion investment in 4.2GW of conventional nuclear technology Sizewell C in Suffolk, led by French giant EDF (PAR:EDF).

Amidst this flurry of investment, there are fears Scotland could miss out on the economic and industrial benefits from a nuclear renaissance in the UK.

Others are sceptical, or outright derisory, of the ability of the nuclear sector to deliver on its promises and say its contribution to net zero targets will be virtually meaningless.

A recent push to develop nuclear power in Australia has also been criticised as a way to delay the transition away from fossil fuels.

But with billions set to be invested in nuclear facilities in the UK in the coming decades, what, if anything, will it mean for Scotland?

UK nuclear SMR competition

State-owned Great British Nuclear (GBN), which was established in 2023 to support the delivery of new nuclear power in the UK, has started negotiations with four shortlisted companies seeking to deliver SMR designs that could be operational by the mid-2030s.

GBN said any of the designs submitted by Rolls Royce SMR, Holtec, GE Hitachi and Westinghouse “would be fit to use in the UK nuclear programme”.

Following negotiations, GBN plans to take two SMR projects to a final investment decision by 2029.

The competition is part of a UK government goal to deliver 24 GW of nuclear capacity and revive British capability in the sector.

With communities in northern England and Wales on the cusp of billions of pounds in investment, is Scotland set to lose out on thousands of jobs and a low-carbon transition opportunity for its oil and gas sector?

The world’s nuclear renaissance

After Japan’s Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011, investment in nuclear energy plummeted around the world, as did public support.

Japan drastically reduced its nuclear output, while Germany followed through on plans to phase out nuclear power by 2022.

Elsewhere, Spain and Switzerland similarly decided not to build new nuclear power stations shortly after Fukushima.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), around 48 GWe of nuclear capacity was lost globally between 2011 and 2020.

In that time, 65 reactors were either shut down or did not have their operational life extended.

But in recent years, interest in nuclear power appears to be rebounding.

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and the subsequent global energy crisis, has seen governments around the world look to nuclear as a more secure and stable option.

Nuclear energy is also gaining appeal in the fight against climate change due to its low carbon intensity and its ability to support intermittent renewables.

AI goes nuclear

Perhaps the biggest recent shift in sentiment has come due to the rapid rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and the energy-intensive data centres associated with it.

In 2024, major technology firms including Amazon, Google and Microsoft have all invested in nuclear technology, with SMRs a particular focus.

The renewed global interest in nuclear energy saw the former Conservative government establish GBN in 2023 to run the SMR competition.

While there are questions over what direction the new Labour government will take, in its manifesto the party promised to “end a decade of dithering” on nuclear policy.

Labour also pledged to deliver Hinkley Point C and said SMRs “will play an important role in helping the UK achieve energy security while securing thousands of good, skilled jobs”.

An energy transition opportunity for Scotland?

Nuclear is also seen as a “levelling up” opportunity for the UK, with much of the proposed investment set to occur outside of the southeast of England.

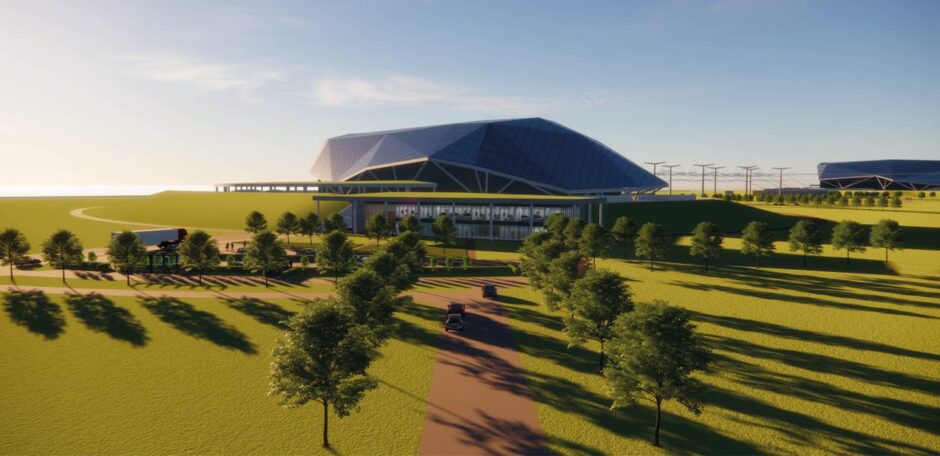

Rolls Royce is building a manufacturing and testing facility in Sheffield, and Holtec has also selected South Yorkshire as the preferred site for its planned £1.5bn SMR factory.

Meanwhile, under the Conservatives the UK government proposed new nuclear plants in northern Wales at sites near Wylfa and Trawsfynydd.

Although Labour reportedly considered scrapping the plans, energy secretary Ed Miliband has said nuclear has a “crucial role to play in powering Britain’s clean energy future”.

But in Scotland there are currently no plans for new nuclear development due to the longstanding opposition of the SNP government, which has planning veto powers.

Opposition to nuclear energy has a long history in Scotland, beginning in the 1970s with the construction of the Torness Point reactor in East Lothian.

According to the University of Glasgow, Scottish nationalists and nascent environmentalist environmentalists both saw nuclear energy and nuclear weapons as highly interdependent.

The location of the UK’s Trident nuclear submarines at Faslane remains a sore point for the SNP administration to this day.

Earlier this week, Scottish energy minister Gillian Martin reiterated the government’s opposition to nuclear energy in a Holyrood committee appearance.

Martin said “there won’t be consent given” for new nuclear projects in Scotland “with the current technologies”.

The SNP’s continued opposition to nuclear power has led to accusations the party is “stuck in the past”.

Nuclear ‘disconnect’

Speaking to Energy Voice, Andrew Bowfield from the Manufacturing Technology Centre (MTC), an academia and industry backed research technology organisation (RTO), senior business development manager Andrew Bowfield said there is a clear “disconnect” between the UK and Scottish governments on nuclear policy.

He pointed to plans to the proposed nuclear sites in Wales as examples of the investment Scotland could miss out on.

“There is a danger that north of the border misses out on jobs, on technology, on growth, in a low carbon sector, which Scotland is very pro,” he said.

“It wants to be the home of renewables, it wants to be an exporter of energy, and Torness is a highly successful nuclear power station which shows that Scotland can provide the skilled workers to deliver new nuclear on the grid consistently and safely.”

Bowfield said he wants “the entirety of the UK to benefit from what’s coming down the pipeline” in the nuclear sector.

Oil and gas transition opportunity

As Scotland and the UK transition away from fossil fuels, renewable energy sectors such as offshore wind and green hydrogen are often touted as transition opportunities for oil and gas workers.

But Bowfield said there are also “huge” opportunities for the both the oil and gas workforce and the supply chain in nuclear.

“There’s a prevailing idea that you’ve got to be a nuclear engineer to work in nuclear, it’s not true,” he said.

“In reality the requirements for nuclear engineers are probably five to 10% of the workforce.”

“They may well be engineers, but they will almost certainly be trained in mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, they come from your traditional engineering backgrounds.”

Despite concerns about the local economy in places like Aberdeen, Bowfield said he is optimistic about the city’s net zero future and believes there is a place for nuclear.

“At the moment, the SNP are very clearly anti-nuclear and that’s why Scotland doesn’t appear on any plans for new nuclear in the UK,” he said.

“But fundamentally, there are huge opportunities if we grasp the nettle. If we deliver SMR, AMR, fusion, the demands on skilled people right across oil and gas or any other sector is going to be vast.

“There will be plenty of opportunity, we need more people.”

Beyond net zero 2050

While many see SMRs as a cheaper route to reliable, carbon-free, stable power generation, critics say the technology will have a negligible impact on mitigating climate change.

A report by the Institute for Energy Economic and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) found SMRs remain expensive, slow to build and “too risky” to play a significant role in the transition away from fossil fuels in the next 15 years.

The IEEFA said in a separate briefing that more immediate solutions for growing electricity demand from data centres are already available.

These include combining renewables such as wind and solar with battery storage or investing in geothermal energy.

But Bowfield said he doesn’t think direct comparisons with renewable energy projects are fair.

“Anybody using nuclear is a big fan of renewables, not only should we be doing that, we can do that [as well],” he said.

“The problem is land usage. For offshore renewables… you need to build wind farms with either huge blades or over a large area, sometimes often both, in order to generate the economies of scale.

“For battery storage or solar photovoltaics, they rely heavily on critical mineral supply in international complex supply chains, some of which are in delicate political and war-affected areas so their supply can’t be guaranteed.

“Geopolitically, some of those are processed in less than friendly states, so the idea that any Western nation should be beholden to complex supply chains, particularly which flow through less than friendly countries, I think that’s naive, and I think it’s over simplistic to suggest that’s a potential solution.”

Nuclear build times

In addition, Bowfield said while criticisms around nuclear build times are “absolutely justified”, the UAE recently delivered a large plant “on time and on budget” in 2017.

He said delays in the UK stem from not building a large scale power plant prior to Hinkley Point C since 1995, leading to a “moribund supply chain in the interim”.

Independent energy sector analyst Kathryn Porter has also advocated for the UK to further invest in nuclear power.

Porter argues nuclear energy has a lower levelised full system cost compared (LFSCOE) to wind and solar.

Porter blamed long build times on overly stringent planning requirements and “hyper conservative” regulators, pointing out UK officials required around 7,000 changes to reactor designs that were already approved in France and Finland.

“Nuclear is not cheap – although arguably it is cheaper than intermittent renewables when the all-in cost to the consumer is properly calculated – but net zero itself is not going to be cheap,” Porter wrote.

“However, nuclear does not have to be as expensive as it currently is, nor does it need to take as long.”

UK has ‘deep reservoir of experience’ in nuclear

Bowfield said he believes criticisms around costs and timescales, while justified, largely stem primarily from a broader “anti-nuclear stance”.

“There is no route to net zero 2050 that does not pass through nuclear,” he said.

“It is impractical and impossible to deliver 2050, for the UK in particular, without nuclear power.”

Investing in nuclear energy is simply “pursuing a place where Britain used to be”, he added.

“[The UK] was the first country to commercialise nuclear power and therefore it has a deep reservoir of experience with the technology,” he said.

Bowfield said with projects having a 60 to 80-year lifetime, nuclear will provide “ongoing capacity for the UK to maintain net zero beyond 2050”, as well as securing skilled jobs in manufacturing for the same timeframe.

“It offers us the chance to adopt a far more flexible, a far more advanced grid than the rather monolithic block we have at the moment,” he said.

“I’m not suggesting it doesn’t come without a significant price tag, but you’ve got to start moving forward.

“You can’t delay and procrastinate about the modern grid until it’s too late, those decisions need to be taken now.”

Nuclear energy and British manufacturing

The nuclear sector is also attracting attention in the UK as a way to revive British industry as an export industry.

Bowfield said the UK currently lacks large scale manufacturing capability for nuclear projects.

“Steam generators, the large boilers, these things don’t tend to be manufactured in the UK, we’ve lost that capacity,” he said.

Bowfield said the UK will not be a large enough market on its own to develop SMR technology and capability.

With Rolls Royce, Holtec and GE-Hitachi targeting SMR exports Bowfield said “there’s a great opportunity for gross value add from export markets”.

Other advantages for the UK include its leading nuclear research institutions, and existing advanced manufacturing capability in the aerospace, defence and automotive sectors.

“In fact, we’re probably one of the best nations in the world for development of advanced manufacturing processes and technology,” he said.

“Where we traditionally struggle is converting that into commercial supply chains. But I think we can do that, and I think that is one of the focal points for Great British Nuclear.”

Nuclear scepticism

While the nuclear industry continues to highlight the potential economic benefits, with forecasts of 123,000 employed in the sector by 2030 with salaries often higher than those working in renewables, many experts are still not convinced.

Alongside cost concerns and lengthy construction timelines, researchers around the world have highlighted risks around nuclear waste and climate vulnerability.

University of Greenwich emeritus professor of energy policy Stephen Thomas is one of the more vocal critics of the UK nuclear strategy, with a recent paper he co-wrote declaring the GBN project is “bound to fail”.

“For decades UK governments have been seduced by claims from the nuclear industry that, this time, a major nuclear programme will go to plan,” Thomas wrote.

“More than ever before, the latest programme will be dependent on huge quantities of public money with financial risks falling squarely on the public.”

Thomas argued the nuclear sector’s contribution to achieving net zero by 2050 will be “nugatory”, with a lack of suitable sites to reach the ambitious 24 GW target.

Military connections

He also argued the UK’s “undying commitment” to civil nuclear energy stems from its links to the military.

“Civil nuclear energy supports key capabilities and skills necessary for the maintenance of the UK’s nuclear fleet and weapons and provides a hidden subsidy from the taxpayer to the military,” he wrote.

“Hence, civil nuclear helps to secure the UK’s international status, including membership of the UN Security Council.

“While military links may be a contributory factor in the development of civil nuclear power, it does not signify that it is an intrinsic reason for its survival.”

Amid ongoing debate over cost, climate, safety, planning and economic investment, geopolitics cannot be discounted as a factor in the renewed interest in UK nuclear.

Permanent UN security council members Russia, China, the United States and France are all upping their investment in nuclear energy, alongside the UK.

For Scotland then, the nuclear debate is perhaps not just a debate about economics, the energy system and the environment.

It’s also a debate about whether Scotland should seek to retain its place at the table of nuclear armed powers alongside the rest of the UK.

Recommended for you