The energy transition is seen as marking a shift away from the “bad old” habits of the fossil fuel industry, but accessing the strategic resources pose their own often-overlooked problems.

These new resources, such as cobalt, lithium and manganese, are essential to cutting emissions and limiting climate change. But new developments pose their own challenges, which may yet come to hamper uptake of alternative resources.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has suggested demand for minerals to support the energy transition will double to 2040. If the world took the steps required to limit warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius, demand for these minerals would quadruple.

Cobalt is perhaps the leading example of a contested mineral that will play a key role in the transition. Congo Kinshasa accounted for around 70% of supply in 2019. Russia and Australia provide around 4% each. Cobalt is mostly produced from copper mines.

At a forum last week in Kinshasa, a number of high-ranking politicians and executives got together to talk over improved ways of pursuing opportunities.

Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi said the country’s minerals provided it with a “strategic position to influence the global renewable energy transition”.

Building power

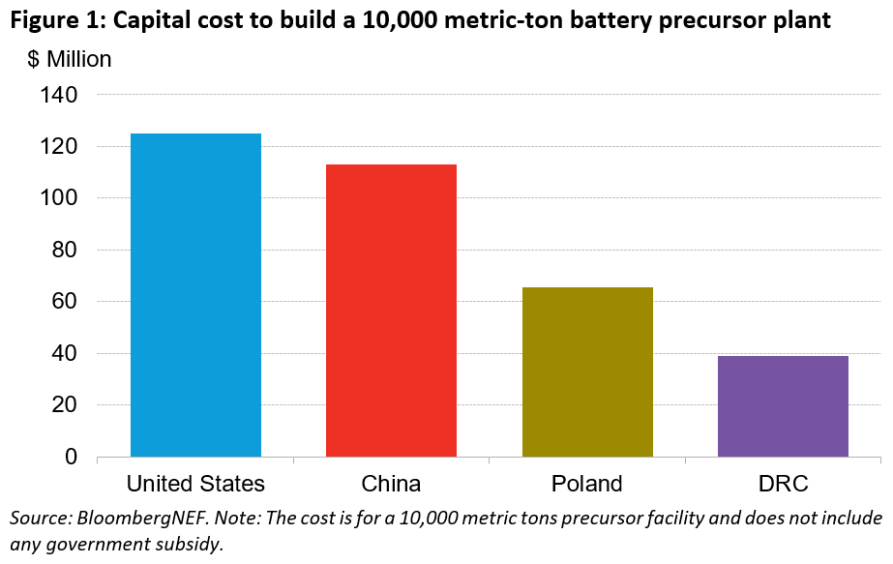

In particular, a new study from BloombergNEF (BNEF) was touted as showing that building a 10,000 tonne battery cathode precursor plant in Congo would cost only $39 million. This would be cheaper than Poland, China or the US.

Producing in Congo Kinshasa would also have a lower environmental impact, the study said.

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) deputy executive secretary Antonio Pedro, in an interview, said the extractive business had been “modelled on those from colonial times. Most mines and extractive industries are still enclaves with no links to the local economy.”

There have been efforts in the past to tackle this challenge. “It’s different this time around,” he said. “BNEF has strong credibility and it has come and said loudly that [Congo Kinshasa] beats any competition.”

Finding demand

Europe is becoming the largest market for electric vehicles (EVs), Pedro continued. Currently, it imports most batteries from China and South Korea. The European Union is taking steps to improve supply chains for batteries, though.

“Europe could start producing its own batteries. But then it is caught up in the same problem of having to import raw materials. As a result, carbon credentials will not meet battery passport criteria,” Pedro said.

“If you were to manufacture batteries in Congo, your carbon credentials would be extremely good,” he continued. Poland is one major competitor, producing battery precursors close to vehicle manufacturing centres. “But they use coal as their energy – so the carbon credentials are very poor.”

Cobalt demand could be anywhere from six to 30 times higher than today’s levels, the IEA said, depending on how batteries evolve and climate policies. Existing mines, and projects under construction, would provide only half the required volumes in 2030.

The US Department of Energy (DoE) has described cobalt as having the “highest material supply chain risk” for electric vehicles (EVs). It reports that for each EV battery with 100 kWh of storage, up to 20 kg of cobalt are required.

Kinshasa expects that cobalt demand will double from 145,000 tonnes in 2020 to 290,000 tonnes by 2030.

While Congo Kinshasa may produce much of the world’s cobalt, China is the world’s largest refiner of the resource. Its share of global cobalt processing is around 80%.

Local challenges

“It is unsurprising that the government of DRC is pressing to retain a larger share of the value chain in battery manufacture,” Bracewell partner Gordon Stewart said.

He drew a parallel with oil-rich African states. These have pushed investors to “build refining capability onshore rather than exporting crude and having to import refined hydrocarbons, leaving the considerable refining value offshore and exacerbating balance of payments deficits”.

Companies would consider how much of the process they could transfer to Congo Kinshasa and other destinations, he said. “It may be efficient to refine the minerals close to the extraction but it’s unlikely to be optimal from a supply chain perspective to manufacture end-user products such as the batteries themselves, so far away from the final market.”

There may be logistical challenges in such locations, such as a need for additional power generation investments and transportation.

Stewart said international companies “will also have sensitivities around ensuring adequate protection for proprietary IP and the legal regimes available to secure it”.

There are certainly challenges in the short to medium term, Indigo Ellis, associate director at strategic advisory firm Africa Matters said.

“Domestic manufacturing has too many hurdles to overcome to be a viable option. Immediately, the DRC government must focus on developing the infrastructure and energy necessary for future production growth, and supporting investors who are seeking to explore for other green minerals, including nickel,” she said.

Teaming up

One area of potential interest would be in regional collaboration. Ellis cited SADC or some focus from the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could help tackle some of the Congolese hurdles.

“However, Kinshasa is wedded to the idea of hosting the production site, so politically, it would be a difficult bridge to cross,” she said.

Such a concept finds favour at UNECA. Pedro said the production of battery precursors would need a host of additional resources, such as manganese and nickel. Gabon and South Africa are major manganese heavyweights and Madagascar and Botswana have nickel.

Such co-operation would “enable us to move even further up the value chain”, the UNECA official said.

Legal concerns

Along the way, there are challenges around investments in Congo Kinshasa. The country has a reputation for opaque business deals.

The Sentry issued a new report this week highlighting allegations around the Congolese mining sector. Based on leaked documents, it raised allegations around “state capture” and links between various Kinshasa officials and Chinese companies.

Another aspect that people must increasingly bear in mind is that of local working conditions.

Stewart raised a potential tension in the push to tackle climate change. “An interesting dynamic inherent in the ESG conversation is the potential for tension between the “E” and the “S” and the “G” given the supply chain associated with the minerals required for the energy transition technology,” he said.

“The electrification of the UK’s transportation improves the air quality in London and reduces the end-user carbon footprint but potentially comes at the cost of increasing damage to natural habitats and use of labour subjected to less robust health and safety and working conditions in the countries sourcing the materials.”

Scrutiny

One way to tackle this is through increased consumer awareness and legislation. The Bracewell partner noted changing laws in Europe on this topic.

“Legislatures such as in France and Germany have passed laws requiring international companies above certain thresholds to take responsibility for understanding their entire supply chain with respect to ESG and human rights considerations and thereby requiring producers to operate responsibly,” he said.

Africa Matters’ Ellis described tracing supply chains as “one of the biggest threats to Congolese cobalt supply”. Tackling pressure on supply chains will involve all parties working together, she said. This would include the national and regional governments, NGOs, mining companies and partners.

“There’s no easy answer to traceability,” Ellis said. “Efforts made so far must encompass stakeholders from across the supply chain to have meaningful impacts on transparency.”

Congo Kinshasa launched its Entreprise Générale du Cobalt (EGC) in March with the specific aim of supporting “responsibly sourced artisanal cobalt”. This small-scale or artisanal sector accounts for around 20% of Congolese cobalt production but has been often linked with child labour.

Throwing down money

Recent discussions have raised the perception that the US has fallen behind China in securing cobalt supplies.

The White House, in June, noted China’s substantial processing volumes and limited domestic reserves. It has been able to reach this through “its aggressive investment in processing capacity coupled with foreign direct investment for ores and concentrates”.

Much of this investment has been in Congo Kinshasa. China made a number of major deals into mining in the Central African state.

Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi has raised concerns about Chinese investments, launching a review earlier this year into the Sicomines project, Bloomberg reported in September. This saw China commit to an investment of around $3 billion in mining projects with another $3bn going into infrastructure.

It is certain that China has provided substantial support for its companies to expand into mining.

China Molybdenum has proved acquisitive, buying up mines such as Tenke Fungurume and Kisanfu from Freeport-McMoRan. The New York Times reported that some of the $2.65 billion paid by China Moly for Tenke Fungurume came from state-backed banks.

Some elements of this move seem similar to China’s support of its national oil companies (NOCs) in the 2000s. With strong state backing, Chinese companies made significant inroads into established oil production hotspots such as Angola.

There were some successes but there were equally challenges in navigating politics around the world. Furthermore, Beijing’s support is not always constant, as can be seen in the rise and fall of Sam Pa, a buccaneering oilman who seized opportunities before vanishing from view, allegedly into Chinese detention.

Great games

Geopolitics are undoubtedly at play, Ellis said. She cautioned, though, that this was something of a simplification, which bypasses the agency of the Congolese government and people.

“The review of Chinese mining contracts – particularly Sicomines – is as much to do with domestic politics and a feeling that the previous administration sold the country’s assets for an unfair price, as geopolitical concerns,” she said.

Beijing has provided some degree of support for its companies to secure overseas minerals. The US has taken a different tack. In April this year, the US DoE set out plans to reduce the use of cobalt in battery manufacturing. There have also been efforts to find domestic sources.

A statement said companies have “recognised the risks of co-dependency”. As such, they are moving to low or no cobalt in cathodes. Most research focuses on nickel, which has good energy density but challenges around capacity fade and impedance.

US research focuses on minimising this nickel challenge, with some early successes, the DoE has said. The government considers nickel to be less of a risky proposition than cobalt.

Nickel imports come from “a diverse set of allied nations”, with 68% coming from Canada, Norway, Australia and Finland. The White House has expressed concerns about future supplies of nickel, though.

It expects Indonesia to dominate production to 2040. No doubt the US will keep a close eye on Jakarta’s processing plans.

© Bloomberg

© Bloomberg